Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

The Digital Economy

Digital, Innovative, and Growing Exponentially

The technologies and inventions discussed in the previous chapters have had a profound impact on the economy and society. Over the last 30 years, a transition has taken place from a traditional physical economy to a digital, information-processing economy. Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee of the MIT Sloan School of Management summarize these changes with the following three “building blocks” [BA14]:

- The digitization of information and the networking of computers and mobile phones

- The massive advances in information technology driven by exponential growth

- Combinatorial innovations

The two scholars believe that humanity is at the beginning of a second industrialization—the dawn of a second machine age. They believe that many more changes will follow in the coming decades. But what exactly has changed?

Digitization and Networking

Digitization refers to the storage of information as a sequence of bits—zeros and ones. Information is “preserved” and processed as data, as discussed in previous chapters.

The second building block is the rapid distribution of data via the Internet: networking. Before the Internet, data was exchanged using physical storage media, such as CD-ROMs, DVDs, or magnetic tapes. Today, it is significantly faster and cheaper. Computer programs can also exchange data with each other, a process known as Machine-to-Machine communication (M2M). The possibilities for communication have increased immensely.

When new technical and social inventions appear, conflicts of interest arise within the economy and society. Typically, the established part of society has little interest in change because they live well under existing methods. Only the “dissatisfied” want change. This was also observed during the spread of the Internet.

The first “victim” of digitization and the Internet was the music industry. In 1999, music was still distributed on CD-ROMs. The music itself was already stored digitally, but the medium was not yet the Internet. It was technically very easy to read a CD-ROM and copy it to an Internet server. Others could then download this “pirated copy” and burn it onto a CD. Many also viewed the music industry as socially unjust because it produced very wealthy superstars while CDs remained quite expensive. This led to the founding of the “music file-sharing service” Napster in 1999 [Hin13]. Here, “pirated copies” of CDs could be downloaded.

The entertainment industry launched the “War on Piracy” (Note: in the US, there are many such “wars,” such as the “War on Drugs,” the “War on Terrorism,” and the “War on Poverty”). This “war” was one of the first confrontations between an old, established industry and the then-new Internet and its possibilities. Napster was very successful and had over 26 million users. The music industry tried everything to stop Napster and initiated many lawsuits. The numerous legal disputes eventually forced Napster to close in 2001. However, many imitators had emerged by then, such as FastTrack, Gnutella, Kazaa, or BitTorrent. Thus, the “war” was far from won for the music industry [Hin13]. The old world, where music could only spread via CDs and radio programs, no longer existed. The many legal disputes were merely drops of water on a very hot stone. The music industry had to find a way to prevent the copying of MP3s. One solution was digital rights management (DRM). This ensures a music file can only be played on a specific device belonging to the buyer and not on other devices. While the files are still easy to copy, they are useless to others. The distribution of this “copy-protected” music happened via dedicated online “stores.” Apple was one of the first companies to introduce the “iTunes Store” in 2003. This, combined with the playback device called the iPod, was a massive success.

Important: The music industry needed a new business model. The old one was threatened by technological development.

It is also important to recognize that the music industry was by no means ideal before the Internet, and incomes were distributed very unequally. When an established industry is threatened by new technology, however, there is often a “whitewashing” of the old conditions.

Videos require significantly more storage space than music. Therefore, the film industry was affected by the Internet later than the music industry. But here, too, there were initially legal disputes with file-sharing platforms. The heavyweights of the established industries tried to exhaust every legal avenue. But as with the music industry, a change in the business model was needed: streaming. One pays a monthly membership fee and can then watch movies selected from a “pool.” The films are loaded directly from the Internet while watching. In the USA, Netflix started this; in Germany, it was Telekom. Today, video streaming data accounts for a large portion of Internet traffic. Technically speaking, old television cables are no longer needed. Everything can be transmitted via the Internet.

Software can also be purchased “online” today. Apple started this with the iPhone and “apps.” These “app stores” have since become very widespread. They exist on all game consoles, PCs, and mobile phones. Books are also available digitally; some companies rely on DRM, others do not. Some also release freely copyable books under Creative Commons licenses, which we will discuss further below.

Exponential Growth

Different Types of Growth

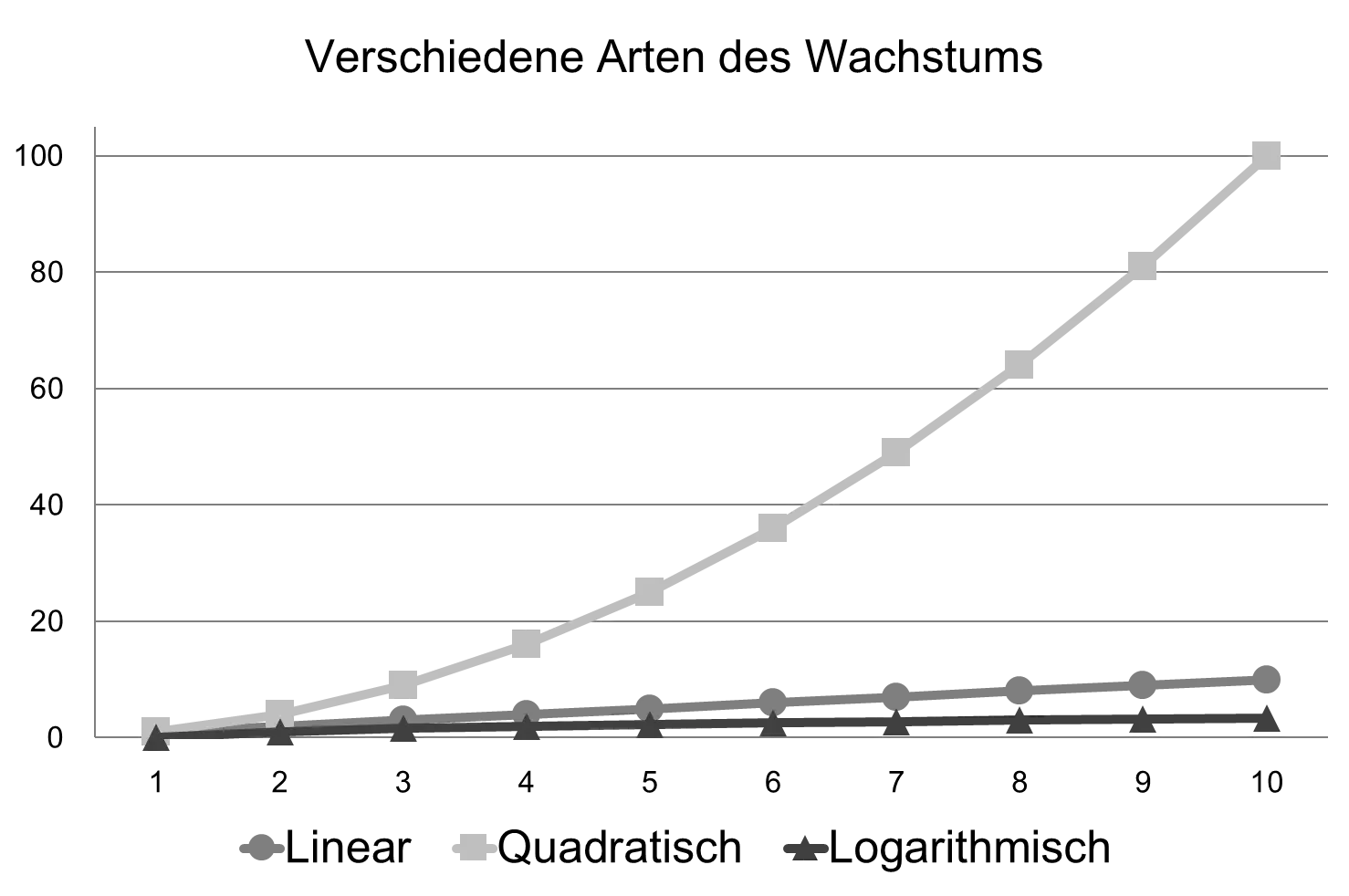

The phrase “We are on the second half of the chessboard” will be heard more often in future discussions about computer technology. It is used to explain particularly large leaps in progress. To explain what is meant by this, however, one must take a step back and cover some basics. There are different types of growth. As an example, the following table lists four typical types of growth:

| n | Linear | Quadratic | Logarithmic | Exponential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 1.00 | 4 |

| 3 | 3 | 9 | 1.58 | 8 |

| 4 | 4 | 16 | 2.00 | 16 |

| 5 | 5 | 25 | 2.32 | 32 |

| 6 | 6 | 36 | 2.58 | 64 |

| 7 | 7 | 49 | 2.81 | 128 |

| 8 | 8 | 64 | 3.00 | 256 |

| 9 | 9 | 81 | 3.17 | 512 |

| 10 | 10 | 100 | 3.32 | 1024 |

The simplest is so-called linear growth. Here, the value always increases by the same amount. In this case, 1 is always added. It can be expressed mathematically as $f(n) = n$ or recursively as $f(n) = f(n-1) + 1$. In quadratic growth, $n$ is always squared, i.e., $f(n) = n^2$. Quadratic growth is superlinear, meaning it grows faster than linear growth. An example of sublinear growth is logarithmic growth, which occurs very frequently in computer science1.

The following function graph illustrates these three types of growth:

Such a function graph is often simply called a graph, but there is then a risk of confusion with the graphs that represent networks. The function graph has two axes: a horizontal x-axis and a vertical y-axis. On the x-axis, values from 1 to 10 are entered, and on the y-axis, the dependent count from the table above. These function graphs allow for a quick classification of growth.

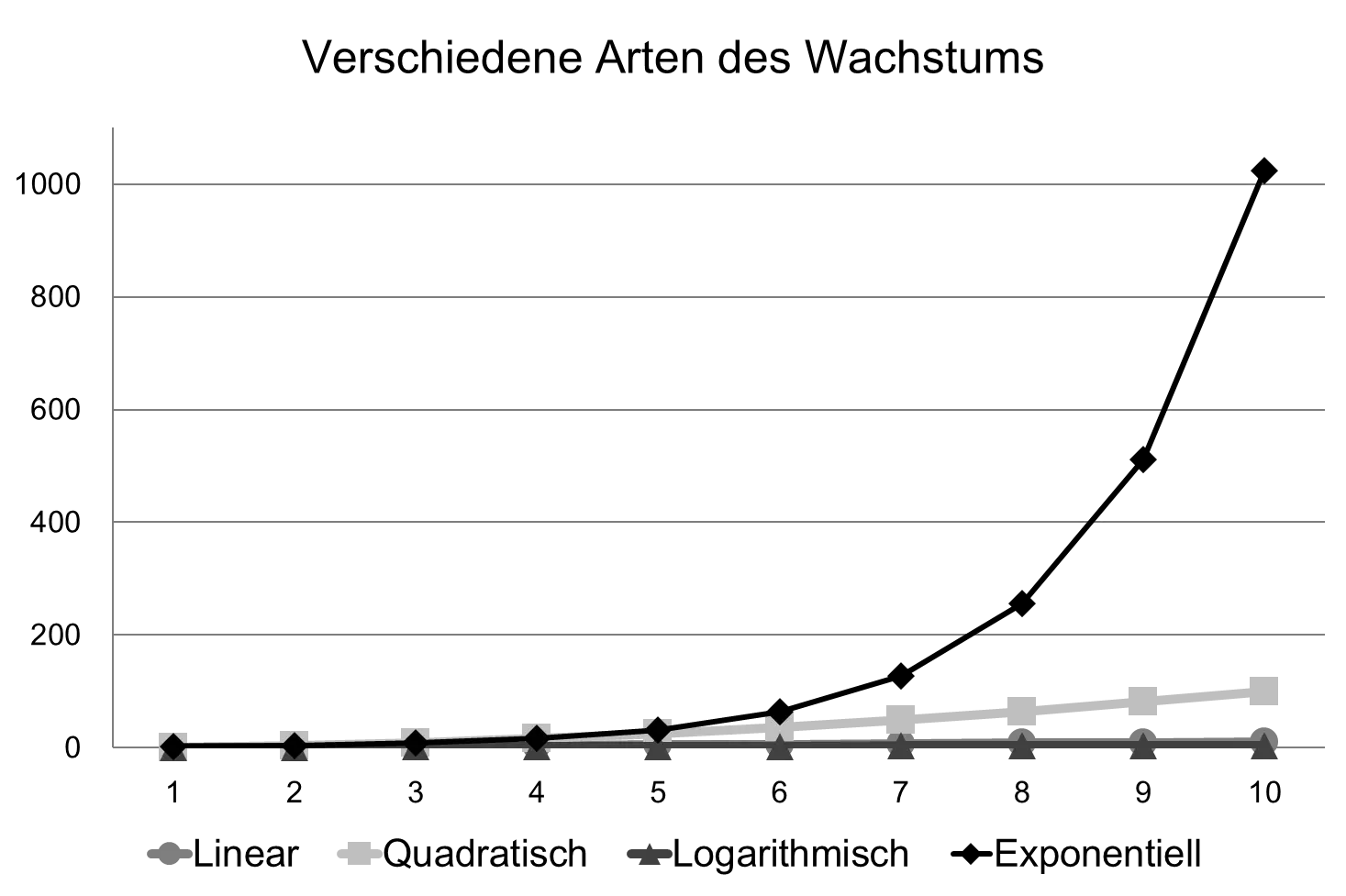

There is another, much more rapidly increasing type of growth: exponential growth. Here, the previous value is always doubled: $f(n) = 2 \times f(n-1) = 2^n$. To illustrate this, the Indian legend of the invention of chess is often told. The inventor of chess presents the game to his ruler, and the ruler was so enthusiastic that he wanted to reward the inventor. The inventor replied that he wished to be rewarded in grains of rice: one grain of rice should be placed on the first square of the chessboard, two on the second, four on the third, eight on the fourth, and so on. The number of grains was to be doubled every time. The ruler agreed and was in for a nasty surprise. For the number of grains became very large very quickly. It is exponential growth to the base 2. A chessboard has $8 \times 8 = 64$ squares, and the number $2^{63}$ (2 to the power of 63) is much larger than the total number of rice grains in the world at that time [Kur06, BA14]2.

Exponential growth is not shown in the previous figure because it would make it difficult to distinguish the other three curves, as shown in the following figure:

These “exponential curves” have remarkable properties that make them difficult to deal with: on a diagram, the slope of an exponential curve initially always looks like linear growth. In the example above, up to a value of 4, there is almost no recognizable difference from linear growth. Later, there is a “turning point” (around 8 in the diagram), and by the end, the exponential curve looks almost vertical. It is possible, therefore, that a scientist observes a process with exponential growth but only notices it when it is too late. Dealing with exponential growth thus requires practice and caution.

Is a lot of growth good or bad? That depends, of course, on whether something positive or negative is growing. The growth of prosperity is obviously good; the growth of poverty is not. Exponential growth can also be very negative, e.g., hyperinflation in the 1920s in Germany and Austria or the spread of diseases.

Moore’s Law

An example of positive exponential growth was identified in 1965 by Gordon Moore: approximately every 18 months, the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles. This means that the complexity of computers can double every 18 months. Engineers can build in “twice” as much “logic” and, for example, increase the number of cores in a multicore CPU3.

However, Moore’s Law is not a “law” in the sense of a law of nature, but an empirical “observation”. The doubling does not occur inevitably. So far, the many researchers and companies involved have always succeeded in doubling the number of transistors because they invented new techniques and, for example, significantly increased the integration density of chips. But this cannot go on forever, and since it is not a law of nature, the end of Moore’s Law has often been predicted. According to the current state of discussion, however, it should hold at least until 2030 [BA14]. And—as we will see in the course of this section—it is very difficult to look further into the future than that.

What does this have to do with the second half of the chessboard?

Exponential growth grows more and more powerfully! At first, the differences are quite small: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16. Later, however, the differences become larger and larger. When a doubling from $2^{32}$ to $2^{33}$ happens in 18 months, that is already a huge leap. Scientists have looked at the development of the number of transistors and found that the 32nd doubling took place in 2006 [BA14]. Computers will therefore make enormous leaps in performance in the coming years. Progress in this area will become faster than in the past.

Extrapolation

If one wants to imagine what the world will look like in 10 years, one could compare today’s world with the world 10 years ago and then “extrapolate”. One determines the differences that emerged over those 10 years and adds them to today’s status. One thinks about how much memory a PC had, how fast the CPU was, how many cores the CPU had, etc., and then adds the difference to today’s values.

But that doesn’t work. For the image created by this “linear extrapolation” is reached much sooner than in 10 years. This would work if the number of transistors grew linearly. With exponential growth, it does not [Kur06].

Let’s do a simplified calculation with Moore’s Law, assuming the number doubles every 18 months. Suppose the 32nd doubling occurred in 2006. How great was the “acceleration” in the 10 years before 2006 (1996 to 2006), and how great was the acceleration in the 10 years after 2006 (2006 to 2016)?4

The answer: The growth in the 10 years after is 64 times greater than the growth in the 10 years before.

And precisely this fact is the reason why humans intuitively misjudge exponential growth and thus misjudge the future. In extrapolation, one must therefore not add the differences, but multiply them.

Important: Exponential growth is faster in the future than in the past. This makes predicting the future difficult.

Other “Growth Laws”

There are other examples of exponential growth. One example from the past is the cost of light; these have fallen exponentially. Formerly, there was only candlelight, which was initially reserved for the wealthy. In the course of technical development, light became cheaper and cheaper, but in the past, one had to work much longer for one hour of candlelight than today for one hour of light from a lightbulb [Gil13, War07]. However, light and electricity have recently become slightly more expensive in some countries as part of environmental protection measures.

Today, in the computer field, not only the number of transistors is growing, but also energy efficiency (FLOPS/watt), hard drive capacity (bytes/dollar), and Internet download speed (bytes/dollar) [BA14]. The amount of data that can be transmitted per second in a fiber optic cable doubles every 9 months according to “Butter’s Law” [SC13, Gil13].

The “Law” of Accelerating Returns

But these are all individual phenomena. Some people have already felt it intuitively, and it’s true: the whole world is developing faster and faster. It’s not just computer technology. After Alexander Graham Bell (further) developed the telephone in 1876, for example, more than 50 years passed before half of Americans had one. With the smartphone (not the mobile phone), it took only 5 years. The whole world has become incredibly “productive” [DMW15].

What an individual person achieves is called their productivity. The productivity of society is then the sum of individual productivities. In the past, due to networking through the Internet, the number of people in product development and research has increased. For example, in China, India, and Brazil, there has been great progress in integrating people into the global economy. More people are working on things now. And productivity has also risen due to computer-aided research and product development. The overall productivity of society—collective intelligence—has increased. And unless wars or other disasters intervene, it will continue to rise. A “positive feedback” loop has emerged that ensures development becomes faster and faster. Futurist Raymond Kurzweil summarized this in the “law of accelerating returns” [Kur06]. According to Kurzweil, progress is even “doubly exponential” because digitization can lead to an enormous increase in growth and not all areas of life have been digitized yet. As soon as a technology can be produced using information technology, the level of technological knowledge will rise exponentially. With the Internet of Things, physical objects will soon be “digitized” (see Section 10.4). With genetics, nanotechnology, and robotics, there are several more candidates for major growth increases on the horizon, according to Kurzweil. In his 2005 book, Raymond Kurzweil wrote that progress doubles every 10 years. In 2015, according to his prediction, there was twice as much progress as in 2005.

Important: Humanity as a whole is developing faster and faster. Therefore, the future is very difficult to predict.

The Digital Economy

The three building blocks of digitization, exponential growth, and combinatorial innovations lead to a digital economy in which much differs from the traditional material economy [BA14, SV98]. The three biggest differences are:

- Rivalrous goods vs. non-rivalrous goods

- Scarcity vs. abundance

- Network effects

Rivalrous goods are consumed during use, such as food. You can only eat a cake once. Non-rivalrous goods, on the other hand, are not consumed by use. Digital data is not consumed; an MP3 file can be listened to as many times as you like. However, storage media like hard drives and USB sticks, and the playback device, do wear out. There are also many intermediate stages between “rivalrous” and “non-rivalrous.” A hammer, for example, can be used by several people in succession; it does wear out, but not quickly. A pencil wears out faster.

Digital goods are non-rivalrous and are also easy to copy. This makes them (almost) infinitely available once they have been created. Only the initial creation costs. This initial creation can, of course, be very expensive, as in the case of Hollywood movies or computer games. The computer game “Grand Theft Auto 5,” for example, had a budget of over 250 million US dollars. Carl Shapiro and Hal R. Varian express it this way: “Information is costly to produce but cheap to reproduce” [SV98]. Digital goods are no longer scarce. Physical goods, such as cars or washing machines, have different properties here. While there is a big price difference between producing 10 cars and 10,000 because mass production can lower unit costs through optimization, even the 10,001st car requires significant costs to produce. Economists call the costs of transitioning from producing $n$ units to $n+1$ units the marginal costs. These usually fall. Proverbially, one can say “the more you produce, the cheaper it becomes per unit.” However, a copy of a file always costs the same and is low from the start.

In all networks, so-called network effects can be observed. Imagine if no one yet had a telephone. Then it wouldn’t make sense for an individual to buy one because most people don’t have one either. The more people buy one, however, the more people can be reached and the more it’s worth it. The utility of a network increases with the number of users. The more users join, the more utility the network provides [BA14, Kad11, EK10].

Due to these three properties (non-rivalrous goods, abundance, and network effects), the digital economy is different from the traditional one. This has led to many changes, for example, in business models.

Innovation vs. Competition

In the past, a company had to perform many services itself. Below are some things a company needed up until the 1990s [Hin13]:

- Space: offices, production facilities, warehouses

- Equipment, inventory

- Mail delivery and receipt

- Printing jobs

- Personnel and HR management: directors, department heads, secretaries, managers, workers, salespeople, notaries

This involved high costs. Today, much of this has been digitized and can now be obtained from other companies as a service. Therefore, a company no longer needs to hire as many people itself, and thus small companies do not require an HR department. Hiring subcontractors, freelancers, and self-employed individuals on a contract basis is not only more flexible than classic employment but also necessary due to specialization. A single company cannot employ an expert in a permanent position for every single issue. Unfortunately, flexible employment models are hampered in many EU countries [Hin13] or there is great legal uncertainty, as in Germany.

Also, a company today no longer needs to produce large parts of its products itself but can order them from suppliers. Chip manufacturers Apple, NVIDIA, and AMD, for example, all have their chips manufactured by the semiconductor manufacturer TSMC. Digital products require no packaging and are not sent by mail. Communication within companies has been significantly improved by email, chat, video conferencing, etc. [Hin13]. And the costs of starting a company have also been reduced in many countries. In Europe, however, it is still more expensive than in the USA.

So today it is relatively easy to become an entrepreneur yourself. This is no longer synonymous with being a “capitalist” because very little capital is required today. What is needed is entrepreneurial knowledge and the business idea.

Formerly, technical progress was much slower. The economy was less dynamic, and everything moved in slow motion by today’s standards. A typical employee completed an apprenticeship and then worked in only a few companies until retirement. Some even worked in only one company their entire lives.

On the whole, global competition in the 20th century was a slow process. In most markets, there were a few globally active dominant companies. These firms competed against each other, such as Ford versus General Motors, Coca-Cola versus Pepsi, or Burger King versus McDonald’s [DMW15]. In this climate, “competition” was the most important topic in management literature, as shown by Michael E. Porter’s 1985 book “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance” [Por85]. Since there were fewer innovations, markets were more static and the economy was mostly a zero-sum game: one firm could only win at the expense of another. It was always about market share. A large part of corporate strategy was therefore devoted to competition: monitoring competitors, analyzing market structure, defending one’s own territory, and attacking other firms [Por85]. “Competition” was the magic word and also shaped American culture in the 80s, from soap operas like Dallas to hip-hop music, where mostly male singers emphasized distinct competitive behavior. At that time, people thought “I can only win if I am better than others, if I defeat others, if I beat others.”

Due to slow technical innovation, markets were “fixed,” meaning they did not change. Therefore, the products sold were all very similar over a long period until the next innovation. A company in such a market can only differentiate products through price and quality: the product must become cheaper. So companies look for ways to cut costs. On the one hand, this is an optimization of the production process, which is to be welcomed. On the other hand, attempts are also made to save on workers and employees. This was achieved, for example, by moving production to other countries. Price wars become increasingly tough in fixed markets. A race to the lowest costs begins. This is bad on the supply side within the company for employees and suppliers, but good on the demand side, as products become cheaper. As explained earlier in Section 5.4, everything in economics has two sides, like the Yin and Yang symbol.

Economists and management consultants W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne found the most appropriate metaphor for fixed markets where competition became “bloody” and merciless: a market with lots of competition is a “Red Ocean”. A market with few competitors, on the other hand, is a “Blue Ocean”. In their book “Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant”, they develop a “program” with which companies can go in search of blue oceans [KM05].

Much of the criticism of “capitalism” or the market economy has arisen because of these “red oceans.” This criticism was partly justified in the past. But it was also one-sided, because critics only looked at the negative phenomena on the supply side, not the price reductions on the demand side. Karl Marx, for example, thought the proletariat would become impoverished over time because workers would earn less and less due to cost pressure. He thought they would eventually earn only as much as they needed to survive (subsistence level). But his prediction was wrong, because new inventions created blue oceans again, and price reductions in the red oceans eventually enabled prosperity for workers because they could buy more products than before.

The economy today is global due to digitization and the associated easy communication possibilities. This “globalization” has different effects depending on production costs and wage levels. A firm in a country with high wages and high production costs cannot compete in a red ocean with firms from countries with lower wages if wages make up a high portion of the costs. For a firm in a country with low wages and production costs, a “red ocean” is not dangerous if only competitors from “high-price countries” are in it so far. Globalization has created many red oceans. A large part of production was, for example, moved or “outsourced” from the USA and the EU to Asian countries.

Today’s economy therefore focuses on innovation rather than competition, and this is reflected in management literature.

Important: Globalization forced companies in high-wage countries to change their strategy from competition to innovation so they could escape competition from low-wage countries. They must create blue oceans.

Peter Thiel, one of the two founders of PayPal and the first external investor in Facebook, expresses the difference between red and blue oceans, between competition and innovation, in his book “Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future” as globalization and technology [TM14]: technology is innovation for him, globalization is competition.

And competition in the future really takes place globally. By the year 2020, 40% of 25–34-year-olds in emerging markets such as Brazil, China, India, or South Africa will have a higher education than those in OECD countries, i.e., the “Western” world: USA and EU. A large part of “complicated” work will then also migrate to emerging markets [Pea15]. Thus, only “complex tasks” remain for the “West,” and those are the innovations.

Agile Companies

Companies have changed significantly in recent decades because they had to adapt to technical progress and globalization. Formerly, firms were mechanistic, hierarchical, based on control, “top-down” planning, and competition. It was previously necessary to achieve economies of scale in production through sheer size in order to reduce costs and survive in competition. Therefore, firms became larger and larger. Today, firms have flat hierarchies, want to be as mobile as possible and react quickly, are “agile” and “lean,” have quality control with SixSigma, optimize their processes with Kanban, and do “knowledge management” in competence centers [DMW15, Cor11, Hin13].

Waterfall vs. Agile

A good example of this changed perspective is software development. Formerly, software was developed according to the so-called Waterfall Model. Here, individual steps were processed in order:

- In Requirements Analysis, it was determined what the customer wants to achieve with the software. What data is entered and what is output?

- In the Specification Phase, a rough model of the software was created. How is the software divided into components, how do these parts talk to each other, what classes are there?

- In Implementation, software developers created a program from the specification.

- This was then tested in the Test Phase.

- Finally, the program was put into operation or delivered to customers.

Software development methodology in the 70s and 80s truly saw this model as the ideal. In certain industries or bureaucracies, it is still partially used today. The problem: knowledge only emerges during the project. It is very difficult for humans to formulate knowledge explicitly. Often, customers don’t know exactly what they need. During requirements analysis, they don’t yet have a precise idea of what the actual program should look like. The second problem is that software projects can also last several years. If the system was finished after two years using the waterfall model, the business situation had often long since changed.

Therefore, software today is developed agilely and iteratively. The preferred method is called “Scrum” [Sch07]. Development in Scrum is divided into short “sprints”:

- The “ScrumMaster” manages the project and coordinates development.

- The “ProjectOwner” is the one who defines the requirements and determines what features the program should have.

- Development takes place in Sprints. These are 1–4 weeks long. Before the sprint, the developer team, together with the ProjectOwner and the ScrumMaster, defines which “features” should be implemented in the current sprint.

- After each sprint, an analysis of what has been achieved and a reassessment of the situation take place.

Scrum allows for features not originally planned to be built into the system and is much more successful than the waterfall model. In Scrum, it is important to always have a running system. Scrum is a fine example of improving productivity through analysis and improvement of work steps, as we already mentioned in Section 4.2. The waterfall model has the same problem as a central planned economy: knowledge must be collected and centralized beforehand. In Scrum, it remains distributed in teams and decisions are made decentrally. In the field of industrial manufacturing, other methods have emerged that can also be used in software development, such as Kanban, Kaizen, and Lean [OF14].

Capital, Knowledge, and Entrepreneurship

The term “capital” originally referred to money. Formerly—when capital was the limiting production factor—only money and the ability to hire workers were necessary to start a company. Machines were then bought with the money, which were still simple to operate at that time. Today, due to progress, a lot of knowledge is required. You cannot start a successful company with money alone. For example, staff must be educated, and the supply chain and processes of the company must be optimized and adapted to the specific conditions of the company and its markets. Interestingly, the term “capital” has been retained and expanded in various directions:

- Human capital is the knowledge of employees

- Structural capital is the knowledge in business models and processes, such as the supply chain

- Relationship capital is knowledge about customers, suppliers, and employees

- Intellectual capital is the knowledge of the company

Thus, one can still say today that a company only needs “capital” and we live in “capitalism.” But that is “cheating” and has clouded the vision for many. As already stated in Section 4.2, knowledge is now the limiting factor.

Important: Knowledge and money have one major difference: money can be easily transferred or exchanged; knowledge must first be learned through years of work.

It is not easy to “transport” knowledge from one person to the next. The “skills shortage” prevailing in Germany is an example of the fact that it is not so simple. Otherwise, people could simply be “retrained.” However, the general public is often not aware that “capital” is no longer enough. In the context of the Euro crisis, it was often discussed in the German media that Greece would be helped if they were lent money or given more time to pay. But money is not the important factor today to help with an economic crisis. It is entrepreneurial and economic knowledge: entrepreneurship. In these countries, the economy must be restarted, and in the knowledge society, that is no longer possible with “capital.” Another example is the fiscal equalization system between states (Länderfinanzausgleich) in Germany. Today, one can no longer help structurally weak federal states simply with the transfer of capital.

In “intellectual capital,” one must distinguish between the following two categories [BA14]:

- User-generated content

- Intellectual property (IP)

User-generated content is created on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Pinterest. The quality of others’ content determines the utility of the service through the network effect. Intellectual property includes, among other things, copyright, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets. Since intellectual property also has a political component, we will discuss it later in the political chapter in Section 11.8.

Innovations

Large companies have a problem: they are often ponderous and bureaucratic. To be competitive, a company must adapt its processes to current products. A successful company optimizes product manufacturing: everything is fixed on current production. If new products are to be manufactured in addition, or if there are major changes to products, then production must be changed. Today, with small changes, this is often not so difficult due to Supply Chain Management (SCM) and Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP). If the changes are so large that the organization of the firm is affected and, for example, departments have to be merged, then this is often only difficult to achieve because employees, parts of management, or unions do not see, support, or even boycott these changes. Often, headlines then appear in the media like “Company X wants to lay off 2,500 people, even though profits are so high.” Thus, the large company cannot adapt to the changed situation, while the press believes that the company is acting purely out of “greed for profit.” The adaptation does not occur, and the firm becomes “more fragile”.

The history of the IT industry, for example, shows that even successful companies regularly have difficulty staying at the top [Chr97]. In the 60s and 70s, IBM led the mainframe market. In the 80s, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), Data General, Wang, Nixdorf, and Hewlett-Packard led the market for corporate computers. In home computers, Commodore and Atari were the most popular. The market for graphics workstations in the 90s was dominated by Silicon Graphics (SGI) and Sun. IBM only managed to set a standard in the PC sector and was then displaced by many clones from Asia. In technical markets, there is a constant up and down due to competition and many innovations. The centralization processes described by Karl Marx, which were supposed to ultimately lead to monopoly capitalism, do not exist in reality.

Management consultant and professor Clayton M. Christensen examined in his 1997 book “The Innovator’s Dilemma” why good firms were not able to adapt to “disruptive”5 technologies [Chr97]. And he developed a set of criteria with which managers can make better decisions in the future. In the following years, management techniques for dealing with rapid technological change were further developed. Today, agility and speed are important. A company should be “lean” and ideally even a “learning organization.” In the summer of 2015, for example, Google announced that the company would be restructured and the parent organization would be called Alphabet. Stock traders use “Alpha” to describe stocks that promise above-average returns, and “to bet” means just that: alpha-bet. Alpha-bet. This reorganization can be seen as Google’s attempt to protect the company against obsolescence and bureaucracy and to make it more robust.

Entrepreneurs

Innovations are therefore often created by new companies because the old ones are too ponderous, too busy, or too uninterested. A large company can also follow the strategy of simply obtaining innovations from suppliers or buying and integrating young innovative companies. Large firms like Apple regularly buy small firms when it is financially advantageous for them.

Today’s business founders are not necessarily people who primarily want to make a career and earn a lot of money. Starting a company is too risky for that. Many entrepreneurs seek meaning in their work, want to change the world, and don’t want an automatic and boring “9 to 5” job [Pea15]. Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal and the first investor in Facebook, describes the entrepreneur as a person with strengths and weaknesses, as a figure of light and shadow, as both an insider and an outsider [TM14]. For an entrepreneur must be an outsider because they need an idea beyond the mainstream. They need something new, a surprise. They must have an idea of something that will have value for others in the future. Something that no one else is thinking about today. In an interview, Peter Thiel asks the applicant the following question first: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?” [TM14]. On the other hand, the entrepreneur must later also be able to convince others, lead a company, and be an “insider.”

Entrepreneurship is still a relatively young topic, but books about self-employment and starting firms are popping up like mushrooms. In contrast to bureaucratic organizations such as authorities, banks, and large companies, many startup firms have flat hierarchies and the opportunity to lead an individualistic life. In a small company, one is not a cog in a large machine. For many young people, it is the only way to lead a creative and fulfilling life. For bureaucracy is based on adherence to hierarchies, rules, and regulations, while a startup is based on lateral thinking, experimentation, and trial and error. Innovations need free people and also free companies.

New Business Models

The Unbundled Corporation

To run a company successfully, it must have a certain vision of itself and the world: a business model. This model describes how the company earns money and what functions individual departments have. The business model is the “architecture” of the company, “the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value” [OP10].

These business models can be described with patterns, so-called business model patterns [GFC13]. With the help of these patterns, one can analyze and describe the structure of companies. Examples of business patterns include direct sales from the factory, flat rate, subscription, or “pay what you want.” We also mentioned the example of “franchising” in Section 5.5.

Management consultants John Hagel and Marc Singer identified the following three fundamental “pillars” within companies [OP10]:

- Customer relationships

- Product innovation

- Infrastructure

Customer relationships are about relations with existing customers and finding new ones. New products and services emerge through product innovation. Infrastructure consists of factories, industrial plants, offices, cars, etc., and the management of these objects.

These three areas differ greatly in their tasks and their “cultures.” Therefore, one should examine in every company whether such an area should not be outsourced to a separate firm. When a company only offers one “pillar,” it is called an unbundled corporation. Since the Internet and digitization enable new types of communication, new types of unbundling have also emerged.

An example of a company that has not yet been unbundled is a taxi company. A taxi company consists of a headquarters with a telephone, a fleet of vehicles, and taxi drivers. A taxi company provides a contact to a driver for a person. It is a middleman between passenger and driver. A taxi company thus consists of the pillars of customer relationships (the telephone number, which is often easy to remember and well-known) and infrastructure. Such a taxi company is not yet unbundled: here, it is to be expected that in the future specialized companies for infrastructure (fleet management) and customer relationships will emerge. Large car rental companies have already started here.

Long Tail

If a supermarket wants to keep a large number of different products in stock, it needs a lot of space and the supermarket’s visitors have to travel a long distance when they want to shop. Therefore, an important task of a merchant is to carry only the goods that also find buyers. Pre-selection takes place by the supermarket operator.

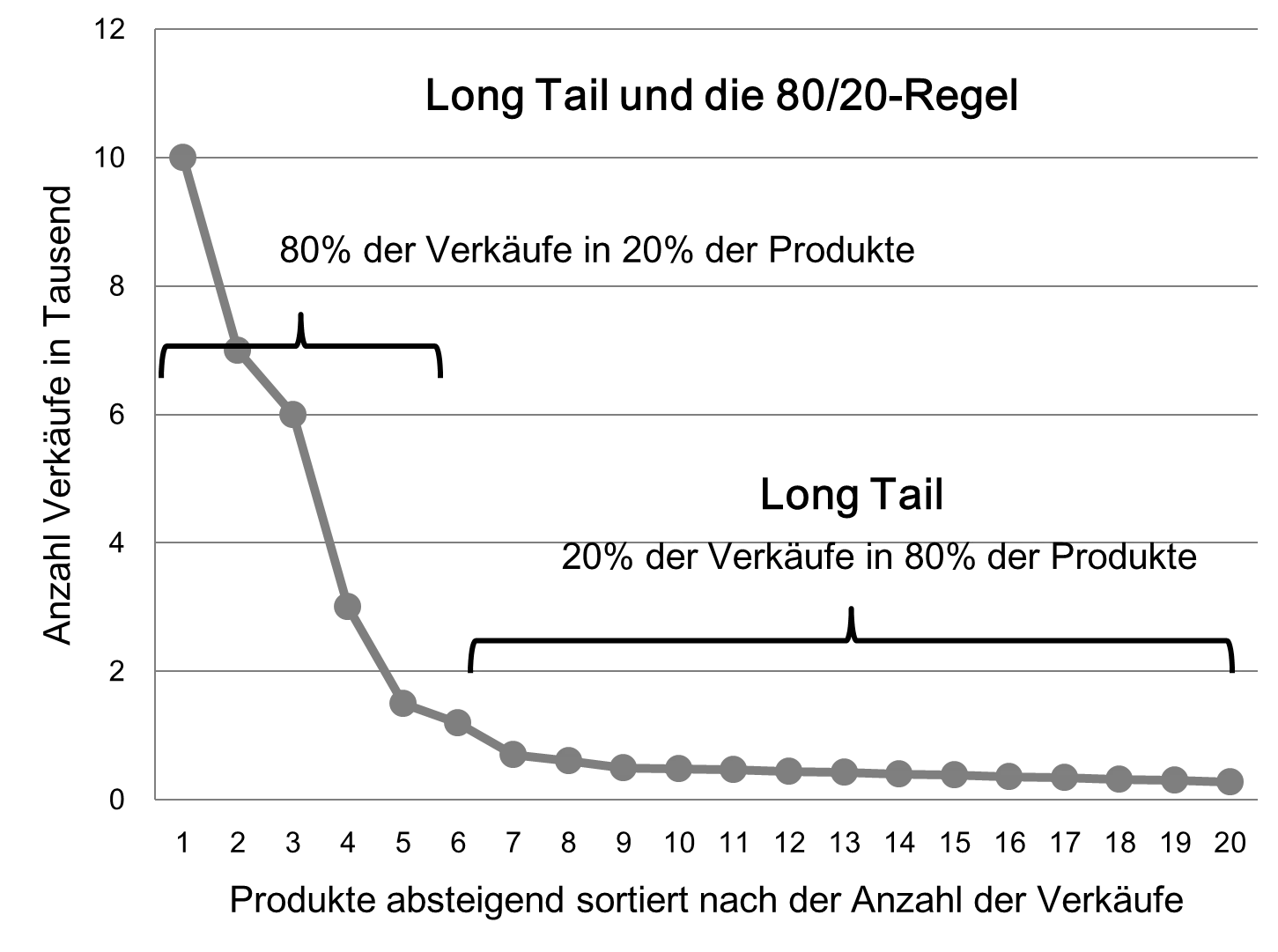

Economist Vilfredo Pareto (whom we already met in Sections 2.4 and 5.2) formulated the so-called 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto principle. In the following figure, the sales of a very small supermarket are shown as a sales curve.

Products are entered on the horizontal x-axis (for simplicity’s sake, just numbered from 1 to 20), and sales on the vertical y-axis. This type of distribution is also a Pareto distribution like the wealth in Sugarscape in Section 2.4. There are typically a few products that sell very well. Most sell only in small quantities because not many people are interested in them. The “Long Tail” is the long end of the curve.

Digital products require little space on a hard drive. They are therefore very easy to keep in stock. This is why online booksellers can offer significantly more different digital books than a bookstore in a pedestrian zone. This has advantages for a less well-known author, as they can directly reach potential readers via an Internet platform. Books by unknown authors are rarely carried by traditional booksellers because the books would take up space in the store.

The “Long Tail” therefore means that one can also offer very specific products and services with the Internet because supply and demand find each other more easily.

Crowdfunding

Some projects or companies can only really take off if they receive financial startup assistance. They can ask banks for a loan or apply for venture capital from private firms. Often, however, such a loan is associated with high bureaucratic requirements. In some cases, a lender also wants to have a say in the company. In any case, it is not easy, and instead of developing the actual new product, the company first develops the required documents and business plans that the lender demands.

But there is a way out here: a crowdfunding website brings together potential private investors with people who need investment capital. The projects and products to be financed are presented on a website, and investors can pledge their financial support. This pattern has already proven itself several times in the past, and computer games, films, and music albums have been financed this way, for example. Crowdfunding is a social innovation. It is an example of how social inventions also follow technical inventions.

Crowdsourcing

Companies often have to outsource certain tasks. Due to the high degree of specialization, a company cannot hire a specialist for all eventualities. Particularly in smaller companies, employees with many skills who can be used flexibly are needed. Specialists must then be “bought in” from the outside. In databases alone, for example, there is such a large variety that a specialist is needed for a specific manufacturer of a database (sometimes even for a specific version). This mediation is often carried out via project exchanges.

A refinement of this principle is the mediation of individual tasks to others. An example of this is the “Amazon Mechanical Turk.” The “Mechanical Turk” was a machine presented in 1769 in the form of a table with a chessboard on it and a puppet dressed in Turkish fashion that could play chess. But it was a hoax, for a human chess player was hidden in the machine [BA14]. At “Amazon Mechanical Turk,” individual tasks are offered, so-called “Human Intelligence Tasks,” which others can complete for payment. These tasks are those that cannot (yet) be solved with the help of artificial intelligence. Human intelligence is still needed, which is why the process has also been jokingly called “artificial artificial intelligence”.

Sometimes companies also push the limits of their employees’ ingenuity. They award research and development tasks to third parties. This is also called open innovation. This is similar to the Mechanical Turk, only the tasks are usually aimed at private researchers and have a high intellectual standard. It is often about scientific challenges [BA14].

This giving out of work to others is called “crowdsourcing.” In crowdsourcing, concerns have naturally been expressed regarding exploitation and compliance with legal requirements. However, it has also been reported that people from poorer countries can achieve high incomes here by comparison. The topic of “outsourcing” touches on a central point of the social market economy, namely the status of work and the employment relationship, and is thus often discussed.

A slightly different way of using the term “crowdsourcing” is used when users can collaborate on a website or a database, as in the case of Wikipedia. The work here is often voluntary and unpaid. Gigantic databases have already been created here. Another example is the classification of images of galaxies as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey [HTT09]. A galaxy can rotate clockwise or counterclockwise. This can be easily recognized by a human from a photo. And in 2008, this did not yet work with artificial intelligence. One sat on countless photos of galaxies but could not classify them automatically. Therefore, a website was built with which volunteers could perform this classification task. Each photo was presented to several volunteers to avoid errors. 50 million classifications were made within one year. Science can also be carried out as a community task.

Two-Sided Market

A two-sided market establishes contact between two different groups. It offers both groups an economic platform. At Google, for example, there are customers on one side who are allowed to use the search engine for free, and companies on the other side who can place advertisements for certain search terms [Shn15]. Facebook offers people a social network on the one hand and advertisements and games on the other.

Two-sided markets are often dependent on network effects. Only when one side is numerous does it become interesting for the other. Game consoles or operating systems can serve as examples here. Only if there are good games for a console is it worth buying the console for players. For game developers, on the other hand, development is only worthwhile if there are enough potential buyers of games.

Cloud

One of the three pillars of a business model is infrastructure. Here, the “Cloud” has fundamentally changed the possibilities—especially for small firms. The entire data center can now be rented as a service. Formerly, firms had to put a lot of money into new computers and new software. One problem was scaling: computers cannot always be expanded at will, and when a computer was at capacity, one had to either buy a new one or artificially limit the service. Today, the entire infrastructure for servers, databases, web servers, etc., can be rented. There are tariffs where you only have to pay for the computing time actually used. Also, any number of computers can often be rented in addition if there is unusually high demand.

“Cloud computing” has advantages particularly for small firms and startups. When a new website is developed, there are initially only a few customers, and with rented computers in the cloud, the costs are not so high. If the website is more successful and word has spread, one simply rents more servers. Here, however, it is important that the software also supports this “scaling” and was explicitly developed as a distributed application [Dav14].

Open Source

Software is coded in a programming language and compiled into executable apps (in Windows, these are, for example, the *.EXE files). The source code is called “source” in English. For software that can be purchased, the source code is a trade secret of the manufacturer. For if a programmer has access to the source code, they know how the software works and could “re-program” the software very quickly. However, the long development time would then not have been worth it for the manufacturer. So the source code was not published.

In the 80s and 90s, the so-called “Open Source” movement arose at American universities. Software should no longer be “commercial” and source code not secret, but software should be “public” and everyone should be able to change the software as they wish. Instead of buying software, you could just download it. The open source movement was partly “the virtual equivalent” of the unconstrained vision from Section 3.4. These programmers generally had well-paid jobs at universities or large American software companies and had an “idealistic” vision of a better world with “free software.”

And through open source, very good and important programs have truly emerged, such as the Linux operating system, GNU, Eclipse, or Hadoop. But the initial vision that all “commercial” software could be replaced was not realistic. With open source, already known software was initially rebuilt rather than truly new innovations implemented. Open source was “competition” rather than “innovation.” The best-known open-source projects, Linux and GNU, were “rebuilds” of already available software.

But the interesting thing was that many commercial firms jumped on the open source bandwagon. Very many companies have invested and “participated” in open source by allowing their developers to have time for open source projects. The companies disparaged as “information capitalists,” such as Google and Facebook, have already made a lot of open-source software available to the general public. According to its own website6, Google has already published 900 open source projects, such as the mobile operating system Android, the web framework Angular, and the V8 JavaScript engine. From the perspective of a software developer, these companies are also doing something good.

Overall, open source has democratized the software market. Small developers can achieve success very quickly here with the right community. And the success of open source has led to imitation in other areas. The so-called Creative Commons license has emerged. If you publish a work under the Creative Commons license—be it a book, a graphic, a piece of music, or indeed software—then you have the following options:

- Is anyone allowed to further process and also publish the work if they name the source?

- Is the work allowed to be used commercially?

These licenses are now very widespread. One often recognizes these works by the “Open” in the name. For example, “OpenStreetMap” is a non-commercial world map. Collective intelligence can grow significantly faster through “open” models. The speed of progress has increased enormously.

Data as Economic Value

Data contains information, and information has value because it can be used to reduce uncertainty. With the help of data, processes can be examined and optimized, new customers found, new medicines discovered, traffic flows optimized, and the environment protected. Data is an economic good. It can have enormous value, both in business and in science [PF13, Dav14]. In the chapter on Data Science, we already mentioned it: you cannot tell by looking at data what knowledge is hidden in it and thus not what value it might have for others. This leads many firms to “collecting data in reserve”. Storing data is relatively cheap if it could still be used.

There are many different ways a company can work with data. Data aggregators, for example, collect data on certain areas and offer it back in combined form [Cor11]. There are, for example, websites for comparing products that have all the test reports about a product. Films are compared at “Rotten Tomatoes”7 and films, series, and video games at Metacritic8.

Many new applications combine different types of data: social data from social networks, local data about the environment, and mobile data from the phone result in “SoLoMo” apps (“social,” “local,” “mobile”), such as Foursquare9 [BA14].

However, the creation of data involves costs. Often it is advantageous to purchase certain data. In addition to commercial data, there is now also “open-source data,” such as from the following sources [CM16]:

- US Government: http://www.data.gov/

- European Commission: http://open-data.europa.eu

- World Bank: http://data.worldbank.org/

- Music: https://musicbrainz.org/

Many other countries offer statistical data of their countries “openly.” A data “culture” is emerging here.

Social Networks and Democratization

A social network today is usually a website where you can register and create your own profile. You can become friends with other users in this network and send them personal messages. Furthermore, you can publish messages for a larger group of recipients on your own page. Many social networks offer ways in which the messages of other users can be rated: the famous “Like” button.

A social network is an example of a so-called multi-sided market: First, the network offers users the opportunity to meet other people and exchange ideas with them. Second, the network operator can show users personalized advertising from other companies. And third, the operator company receives valuable knowledge about society in the form of the social graph. Friendships and users’ “likes” are stored in a graph database. It is a database with many statistical data of its users, such as age, number of children, or place of residence. But it also contains the relationships between people and to other things, such as music bands, television films, and computer games. These connections offer previously undreamed-of possibilities for sociological research. Examining these relationships is possible for the first time on such a large scale in human history.

The operator company of the social network can sell the “knowledge” present in the social graph to interested companies. Facebook does this, for example, with “Audience Insights.” Here one must make it very clear that this is not about address data or phone numbers and email addresses, but about “social data”: which music bands you think are great or which films you have seen.

But who owns this data in the “social graph” (without address, telephone number, email address)? The user themselves stated that they like a certain computer game. Is that the user’s data? Technically speaking, the data is stored on the social network’s computers. For as soon as they enter the data on a social network website, the data has left their PC or smartphone. It is no longer “their data.” The only exception here are cloud services that sell storage space. There, “their data” must also remain “their data” and may not be passed on.

There are critics here who fear “surveillance” by these “data octopuses” and, for example, demand more state data protection. The fears are, of course, justified on the one hand, for companies are often no angels and have already used their market position and size against people’s interests. Companies are also forced to work with state organizations, such as the National Security Agency (NSA) in the USA or in the case of Facebook censorship in Germany. But on the other hand, no one is forced to use a social network, and certainly no one is forced to “publish” all their data there.

Many problems in the past were due to the fact that the medium was still “new territory” for many users and there were no alternatives. Facebook, for example, baited many users with games such as Farmville or Candy Crush. One only had to register and already had a few nice games. In return, many people gladly “sacrificed” their data. And who wants to forbid them? It is their data. Who wants to dictate to them to whom they give their data and to whom not? That would not be data protection, but data paternalism.

Over time, the market for social networks will also become more critical because it is no longer something new. Something new always fascinates people. In the future, users will pay attention to what is being done with their data, and the providers of social networks will have to adapt to this. This also happened in the 80s in the food industry with organic food and more recently with vegan food.

Democratization

The Internet enables direct communication and direct search. With the Internet, many “middlemen” can be bypassed. In countries with state-regulated or even censored television channels, information can be checked on the Internet. With the help of the Internet, the costs of starting a small company have dropped extremely. Everyone can run a media company, everyone can start a website with an online shop. Formerly, you had to pay expensive rent in a pedestrian zone for that. Many can now receive job offers to which they previously had no access. The Internet is thus also a means of making the world more democratic and increasing equality of opportunity.

Low-Cost Education

The costs for education and knowledge have been greatly reduced by the Internet. The best-known example is Wikipedia. Wikipedia now comprises more than 50 times as much information as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, the most respected encyclopedia in Great Britain. Formerly, encyclopedias were created by a number of employees of a company. Wikipedia, on the other hand, was created by thousands of volunteers from all over the world. Anyone can register and make suggestions for changes, which are then voted on democratically. Wikipedia is a democratic encyclopedia. The socialist slogan “Of the people, by the people” would fit well here. Ironically, however, Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, came across the ideas behind Wikipedia through the article “The Use of Knowledge in Society” by Friedrich A. Hayek [Hay48], which we already covered in Section 5.3. Knowledge is distributed throughout society.

Many universities now also offer courses on the Internet, such as the world-famous Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the technical field10. Many online schools for children and adolescents have also emerged, such as the Khan Academy. Under the keyword “massive open online courses” (MOOC), many further offers can be found.

Platforms as Middlemen

The Internet makes it possible for supply and demand to come together globally. This has led to the so-called sharing economy, in which private individuals can enter into business relationships with each other. An example of this is renting living space for vacationers with airbnb. A homeowner can offer an apartment, and apartment hunters can search and book it via the web or an app.

With Uber and Lyft, any car owner can become a taxi driver. Contact with the customer is established via the app. Previously, a taxi company was necessary for this. A customer calls the company’s headquarters, and it provides a driver with a car. This task can easily be replaced by a website and a mobile app. Taxi companies once arose because it was not possible for guest and driver to arrange directly. That is different today. The sharing economy therefore results in major economic changes. There is a conflict of interest between established hotels and taxi companies and newcomers. There have even been violent protests by taxi drivers against Uber in France. Therefore, the new technology is naturally discussed very controversially, and there have also been calls for prohibition and regulation.

Many discussions view the situation as a zero-sum game: what Uber wins, the taxi company must lose. But the market is not fixed, i.e., through Uber, lower-income customers are added. Riding becomes cheaper. It is a non-zero-sum game. Second: if the taxi companies lose something, they are offering something that the market can now produce more cheaply. The prosperity of the overall population increases as a result. They receive the one ride and even keep money left over. So there are winners and losers.

The Arab Spring

In December 2010, street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi was harassed by local police in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid because he did not have a “permit.” After the police confiscated his goods and his scales, Bouazizi set himself on fire in public and died from the consequences on January 4, 2011 [DMW15, TG15, SC13].

It was the protest of a self-employed small businessman against unfair “regulation” by the state. It must be said here that in Germany, he would most likely not be allowed such a stand either. He might be accused of bogus self-employment. He would at least have to register a trade and pay trade tax. It is unlikely that he could feed his family this way, as he probably does not make enough turnover as an individual trader.

In any case, the news of Mohamed Bouazizi’s death spread in the Arab world via social networks in no time and triggered protests throughout Tunisia. The dictator at the time, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, even visited Mohamed Bouazizi in the hospital. But that was of no use, because the population was incensed, and the dictator had to leave Tunisia a few days later on January 14. But the flame was lit and spread to the entire Arab world. The “Arab Spring” led to rebellions in many countries.

Why this “spring” did not then lead to “democratization” is controversially discussed. Organizing an uprising is much easier than developing an “understanding” for democracy in the entire population. This “understanding” is a paraphrase for “knowing how to behave in a democracy and that win-win situations for all are better in the long run.” A democracy must be realized “bottom-up” in society; it cannot be ordered “top-down” or brought about by an “overthrow.”

Economic Growth and GDP

To evaluate the development of the economy, mainstream economics uses Gross Domestic Product (GDP). GDP is the sum of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders over a period of one year. This is the traditional “top-down” view of the economy. One looks at an aggregate, a sum, or an average, and tries to use it to evaluate the current situation of the economy [BA14].

Such numbers that serve as a basis for assessing status or as a basis for decisions are called Key Performance Indicators (KPI). A basic management principle is “what gets measured gets done” [BA14, TG15]. Based on the changes in the KPIs, one can observe the success or failure of one’s own actions. In complex systems, an action always has side effects. And only what is measured can be evaluated. For otherwise it remains unobserved.

However, it is also important that KPIs are interpreted correctly. In the case of GDP, for example, inflation must be factored out, i.e., the devaluation of money by increasing the money supply11.

GDP also has great difficulties in an information and knowledge society because it only measures capital, but not information and knowledge [BA14]. The use of Wikipedia and Google is free. Many magazines can be subscribed to more cheaply on the net. A call via Skype is cheaper than via the telephone. A chat with WhatsApp is cheaper than an SMS. All these services make life better and increase quality of life, because the saved money can be spent on other things. Brynjolfsson and McAfee summarize this nicely with “analog dollars are becoming digital pennies”. But these savings lead to GDP falling! Economists evaluate the increased quality of life as negative because digital services cost less than analog ones. The sharing economy and the open economy have positive effects that do not appear in GDP.

The benefits of digitization are therefore not recognizable in GDP. Unfortunately, this has not yet gotten around everywhere, and “growth in GDP” is often equated with “economic growth.” New metrics are therefore needed. Here, however, economists do not yet agree on successors [BA14]. How can the progress of lower-cost digital products be evaluated? In the meantime, economists must take into account that a large part of innovations does not appear in GDP.

“The winner takes it all”

A long time ago—before the invention of mail order—goods always had to be bought locally in a regional store. If products were just not available, customers then also bought the second- or third-best products. Often you only knew the local products that were available on site. A pedestrian zone in Great Britain in the 80s was still very different from one in Spain, France, or Germany. The products in the supermarkets were also different. Today, much is the same. It is the same multinational firms that offer the same products in the same branches.

Today, through the Internet and globalization, there are global markets. One can find out about all products, either on the manufacturer’s website or on product comparison sites. Thus, one can always buy the “best” product. This led to greater competition among providers. It is no longer enough to be second. On the other hand, a company today also has the advantage that it can offer more diversified products due to the “Long Tail” and supply chain optimization.

Customers benefit from the comparability of goods on the Internet, while firms “suffer.” Due to digitization, there is less room for those who are not the best. In the economy, the motto “The winner takes it all” increasingly applies [BA14]. Competition therefore takes place globally, and all the more important are the “blue oceans”—the innovations.

-

The logarithm to base 2 is the number of times you can divide a number by 2 and the remainder is still greater than or equal to 1. The logarithm of 2 is 1, because you can divide 2 once by 2. The logarithm of 15 is 3, because 15 / 2 = 7 remainder 1, 7 / 2 = 3 remainder 1, 3 / 2 = 1 remainder 1. ↩

-

The logarithm to base 2 is the “opposite” of exponential growth to base 2. It holds that log(2^x) = x. ↩

-

This Gordon Moore is not the Edward F. Moore after whom the Moore neighborhood from Chapter 2 was named. ↩

-

Here is the calculation for the mathematically interested: In 10 years there are 10*12/18 = 6.67 doublings, which we simplify to 6 doublings. If 2006 was the 32nd doubling, then in the 10 years before there was growth from 2^(32 - 6) = 2^26 to 2^32 in the year 2006. And that results in a difference of 2^32 - 2^26 = 4,227,858,432. In the 10 years after 2006, however, there was growth from 2^32 to 2^(32 + 6) = 2^38 and that is 2^38 - 2^32 = 270,582,939,648. That is 64 times! 64 = 2^6 for 6 doublings. In general, this is the 2^k-fold, if the number of doublings is k, because (2^(n + k) - 2^n)/(2^n - 2^(n - k)) = 2^k. ↩

-

A “disruptive” technology replaces the previously used technology. ↩

-

One must be careful today with inflation, because inflation in mainstream economics is calculated as the consumer price index, in which rents, houses, and stocks are not included. Intermediate products in industry are also not included. Finally, a basket index is also calculated, in which “experts” decide on the composition of the basket. Technical devices, such as computers, are also included here. However, technical devices become cheaper due to technical progress and thus artificially lower the inflation index. An index “blurs” the information, as explained in Section 5.3. Today, the term “inflation” is therefore being fudged. ↩