Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

… and Politics

The Political Game

Humans have desires and goals. To reach a goal, one must find a path. One must decide which means can be used to achieve that goal. Let’s assume two “parties” have access to means and goals that are either compatible or incompatible. We can simply apply a table from game theory, which was already covered in Section 3.3 [Gha11]:

| Goals Compatible |

Goals Incompatible |

|

|---|---|---|

| Means Compatible |

Cooperation | Coalition |

| Means Incompatible |

Competition | Conflict |

If both parties have the same goals and both want to use the same means, there are naturally no difficulties and they can cooperate. If they want to achieve the same goal using different means, they are in competition with each other. If they pursue different goals using the same means, they can form a coalition. A real conflict only exists when both means and goals are incompatible. This conflict, in turn, leads to a new zero-sum game similar to the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” or the “Stag Hunt” from Section 3.3. However, in politics, there is also the possibility of transforming the conflict into a non-zero-sum game by moving away from fixed means and goals and working out compromises. Here, both parties can then develop a win-win situation.

When Karl Marx wrote “History … is a history of class struggles,” he overlooked these various possibilities and reduced the history of humanity to a conflict defined by a zero-sum game.

Individual and Economic Freedom

In everyday language, the word freedom is mostly used to express the rights of the individual: freedom of speech, freedom of the press, or freedom of movement. This is individual freedom. Everyone can live their life as they wish, as long as no others are harmed.

Economic freedom, on the other hand, is the ability to act freely in economic terms. How easy is it to start a company? How many laws do you need to know? What taxes are due and how high are they? In some places in the American Wild West during the 19th century, it was enough to paint a sign that said “BARBER” and hang it in the window facing the street. And just like that, you were a self-employed barber. There was a “right to earn a living.” Provided, of course, that enough customers actually showed up. The mercantilism of the Middle Ages, by contrast, was economically unfree. To become a barber, one first had to join a guild and, through years of membership and much goodwill from other guild members, snatch a “license.” The American myth of “from rags to riches” (or “dishwasher to millionaire”) depends on this right to be able to found a company. Because somewhere on the path from dishwasher to millionaire, one must be able to go into business for oneself.

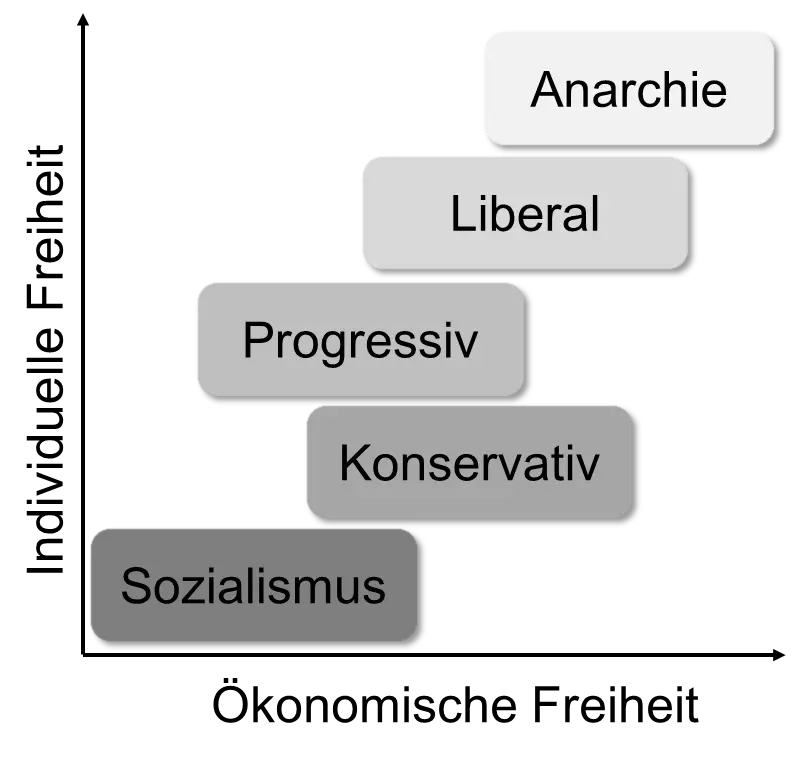

With these two freedoms, one can roughly categorize the usual political directions on the following sketch:

In politics, most countries have two directions: a “Progressive” one (Social Democratic, Green, or Left) and a “Conservative” one. Progressives are generally in favor of more individual freedoms, such as marriage for same-sex couples, freedom of religion, and “alternative” lifestyles, while Conservatives prefer the traditional life model of marriage and children. Economically, however, Conservatives favor less regulation of the economy than Progressives, who want to regulate the economy as comprehensively as possible. An extreme in this representation is Socialism, which is based not on the individual but on the collective. The “Social” in “Socialism” does not come from “socially just,” but from “community.” It is not the individual who decides, but the collective. Exactly who determines the “will” of the collective varies depending on the variant of socialism. In the “real existing socialism” of the Soviet Union, it was the party or the bureaucratic state apparatus, while in anarchist variants, it is supposed to be workers’ councils or syndicates [Mue84]. The individual themselves, however, cannot decide.

Economic freedom also includes the right to property. Regarding property, one can distinguish between consumer goods and means of production. In Communism, according to Karl Marx, the means of production should be “socialized.” Socialists after Karl Marx interpreted this as “nationalization.” A major problem is that the boundary between consumer goods and means of production is fluid. It is therefore not easy to decide when something should be nationalized and when not. This gives the officials entrusted with this task immense power. If a musician plays a song on a guitar and receives nothing for it, the guitar is a consumer good and his property; but if he receives payment, be it a beer, a dinner, or money, then it is a “means of production” for the creation of “entertainment.” According to this, the guitar would have to be nationalized. Officials in a kind of “Ministry of Music” would decide on the distribution of guitars. Does anyone wonder why the best punk bands of the 70s and 80s came from Great Britain and the USA and not from the Eastern Bloc? Because the music industry was not nationalized! On the contrary: in a market economy, people who were dissatisfied with the music produced by the established music industry could start their own record labels with a little money. So-called “independent labels” emerged, which shaped the “alternative” sector. Without private property and the right to start a business—such as a record label, a record store, a fanzine, a mail-order service, or a website—music culture would be significantly poorer, and some musical genres might not have emerged at all. Something comparable can be said about independent computer games. Musicians, authors, game developers, and other creatives are, in a certain sense, also “entrepreneurs.”

Important: The economy and society require innovations; these come from entrepreneurs, and they, in turn, require a high degree of individual and economic freedom.

The Financial System

Today’s financial system is a very complex system, partly even chaotic. Financial systems play an important role in the economy [Fer08]. Today’s financial system—like the rest of the economic system—is a mixture of market forces and state-planned economy.

It starts with money: in many countries, it is a state monopoly. The U.S. Dollar, the Euro, or the Deutsche Mark are or were controlled by states. This is done for reasons of state financing, so that states can more easily take on debt and, for example, finance the military and wars. Section 4.2 described how the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian King Frederick William III had to borrow money from the Rothschilds during the Napoleonic Wars (1792 - 1815) to finance the war. This is no longer necessary with today’s financial system. State monopoly money could also be called “top-down” money. “Market money,” on the other hand, forms “bottom-up” on a voluntary basis. For example, there are people who collect silver and gold coins. In times of crisis, other scarce goods, such as cigarettes, are also used as currency.

The next important point is the capital requirements (equity ratio) of banks, which allow banks to create money out of thin air [Fer08, May14]. Put very simply: if someone deposits 100 Euros at a bank, and there is an equity ratio of 10%, the bank can lend out 90 Euros and only needs to hold 10 Euros as a reserve. On paper, this creates a 100 Euro claim for the saver and a 90 Euro claim for the borrower. If the 90 Euros are deposited at another bank, that bank must in turn secure at least 9 Euros as equity and can lend out 81 Euros. This can continue multiple times and is called credit expansion. This results in different money supplies: M0 equals 100 Euros, and M1 = 100 + 90 + 81 = 271 Euros. Of these 271 Euros now circulating in the economy, only 100 actually exist. Here, money is created out of thin air, and society thinks it is wealthier than it actually is. Furthermore, the system is fragile: what happens if the first customer wants their 100 Euros back? The first bank must pull back the 90 Euros if it doesn’t have enough equity. The next bank must pull back the 81 Euros, and so on. This leads to a chain of “bank runs,” and the system collapses.

Another point is the distinction between active money and passive money. When viewing money from a “normal” perspective, one thinks that behind a 100 Euro bill there are goods worth 100 Euros. The bill exists because it is “backed” somewhere by 100 Euros in goods or gold. Such “backed” money would be active money. Today’s monetary systems, however, are “passive money.” Behind every banknote lies a “debt,” a promise to pay by the central bank or, ultimately, the state. For example, the former chief economist of Deutsche Bank, Thomas Mayer, argues for a new monetary system in his book “Die neue Ordnung des Geldes: Warum wir eine Geldreform brauchen” (The New Order of Money: Why We Need Monetary Reform) [May14].

Important: Today’s financial system is heavily criticized even within the field of economics.

Another planned-economy element is the setting of the “key interest rate.” When banks need money, they can borrow it from the central bank. The interest rate for this borrowing is called the “key interest rate” and is set by the central banks. In the USA and the EU, it has been at historically low levels of under 1% in recent years. So, lately, it has been easy for banks to get money. In the media, this is often referred to as “priming the pump” or “stimulating” the economy. However, interest rates express the relationship between the future and the present; in a market economy, they normally form “bottom-up” and cannot actually be planned “top-down.” In German media in 2014 and 2015, it was also frequently stated that the Eurozone would need different key interest rates because the economies in individual countries were so different. A key interest rate that is too low can overheat the economy, while one that is too high can freeze it.

Important: Today’s financial system is a remnant of a market economy within a planned-economy framework controlled by states and affiliated central banks.

The beneficiaries of this system are the states, which can pay off the interest on their debts with “cheap money” and take on new debt (“refinancing”), and the banks, which borrow money at a low interest rate and use it to “gamble” on the stock markets. A rise in stock prices is then sold in the media as an “economic boom” rather than a consequence of low interest rates. If this policy of low interest rates is carried out permanently, it can lead to previously unknown consequences, such as economic crises and hyperinflation [Mis49, DMW15].

The 68er rock band Ton Steine Scherben sang back then: “Who has the money has the power, and who has the power has the right!”. And at that time, the 68ers assumed that capital was in the hands of the “rich” and the “capitalists.” But: the states or governments “have” the money. The banks are involved because they have the task of providing the indebted states with new loans.

Important: When politicians claim after a financial crisis that “capitalism doesn’t work,” it is a logical fallacy because today’s financial system is not “capitalistic” at all.

Market and State

A Mixture of Capitalism and Socialism

Socialism is characterized by a “nationalization” of the means of production, while “pure” market economy allows no state restrictions on the ownership and operation of the means of production. Thus, there is an entire continuum between socialism and laissez-faire capitalism:

- Extreme Socialism: All means of production nationalized

- Socialism: The “most important” means of production nationalized, only a few free

- Social Market Economy: Some parts of the industry nationalized or cartelized

- Minimal State: Only security and defense are nationalized

- Laissez-faire Capitalism: Everything in private hands

Today, most countries have regulated markets and some nationalized industries. Most people in today’s world therefore live in a system that is a mixture of market economy and socialism. But this “mixture” varies from country to country. In one country, there might be a state postal monopoly, while in another, energy supply is handled by the state. Even the Soviet Union allowed a small share of market economy again in 1921 with the introduction of the “New Economic Policy” (NEP).

The “government spending ratio” (Staatsquote) is the share of government expenditures relative to the gross domestic product (GDP). Today, in most countries, it lies between 45 and 55%. In Germany, for example, it was 44% in 2014, and in France, 57%. Former Chancellor Helmut Kohl is said to have once remarked that “at a government spending ratio of 50%, socialism begins.” Ironically, “Leftists” describe the current economic system as “capitalism” [Sch15], while proponents of a minimal state call it “socialism” [Baa10]1.

Important: Most states today are a mixture of market economy and socialism. Every country has its own specific mix for historical reasons.

It is also quite interesting that people identify with different regulations. For example, in the 90s, there were many discussions about the “German Purity Law” (Reinheitsgebot) for beer. The production of beer was regulated, and certain additives were prohibited. People had grown accustomed to this regulation and identified with it. This was used as an argument against importing beers from other countries. A kind of nationalism emerged that had its origins in the regulation of the industry. More recently, there are similar arguments regarding “chlorinated chicken” from the USA. The use of chlorine for disinfecting poultry is banned in the EU but not in the USA. A kind of “EU nationalism” is currently emerging based on these regulations.

The Optimal Mix?

But what is the optimal mixture of market and state?

A scientific answer to this question has not yet been found. One would first have to clarify what “optimal” should mean in this context. Should people be as free as possible? Or as wealthy as possible? Should everyone have the same amount? Or be paid according to their performance? If we could at least agree on a common goal, we would then have to discuss the means to reach that goal. Can it be done without regulation? If several regulations are available, which one is better? Should the state only create a framework and leave the details to the market? Or should the state determine everything down to the smallest detail? Or perhaps the state isn’t needed at all?

Since a society and the economy are complex systems, a scientific answer to these questions has not yet been possible. Today’s insights from complex systems and agent-based modeling are still insufficient for this. At most, one could take a philosophical position today.

Bottom-up vs. Top-down

From the perspective of complex systems, there are two different ways a society can change norms, rules, and laws:

- “top-down”: the state issues regulations that everyone must follow

- “bottom-up”: society itself develops “unwritten” laws that are later written down

In complex systems, it is very difficult to achieve desired behavior simply through top-down mandates, because parts of the complex system will likely behave differently than expected, leading to unintended side effects (see Section 2.6).

In television discussions, one sometimes hears the phrase “the state must do that.” In economics, a distinction is made between a “public” sector and a “private” sector. The public sector is operated by the state, and the private sector by companies. The public sector is bureaucratic, and the private sector is more profit-oriented (see Section 5.5).

When the state is entrusted with an economic task, such as a postal or letter monopoly, the private sector cannot take over that task. There is a zero-sum game here between the public and private sectors [Cas12]. How are prices for such a monopolized service determined? Since there is no longer a market for it, there are no longer market prices. The monopolist lacks the basis for comparison [Mis49]. The knowledge about operating such a service lies in the hands of state officials. The question of whether the same service could be organized more cheaply, or whether there is potential for savings, can no longer be easily answered. With the term “potential for savings,” one must also think of environmental protection: how many sheets of paper are “used (wasted)” in government offices? How many liters of gasoline could be saved with “fleet optimization” of a state-owned mail carrier? As a rule, the private sector can no longer offer tasks that the public sector takes over. This is because the public sector does not have to make a profit, can offer services below “market price,” and simultaneously incur higher costs since it is funded externally. From a macroeconomic perspective, this is wasteful, as more money is spent on a service than is necessary.

Important: The public sector has advantages due to external funding.

“Bottom-up” processes, on the other hand, can take a long time to fully develop. The advantage of “bottom-up” processes, however, is that they are “grassroots democratic” and can develop great momentum. Environmental awareness can be taken as an example. In the 80s in Germany, environmental protection was initially represented mainly by “The Greens” party. At that time, they were not part of the government, and therefore environmental awareness had to develop “bottom-up.” People recognized the good idea and adopted environmental protection as an additional norm, spent a little more money on organic food, and rode their bikes to work. This happened in the 80s completely without influence from the then-ruling government of CDU and FDP. Environmental awareness prevailed “bottom-up.”

Market vs. State

In politics, however, the perspective of complex systems is still largely unknown. In economic policy, there are mainly two directions:

- Much state and little market (“Left” and “Right”)

- Much market, little state (“Liberal”)

In discussions, it frequently happens that the proponents of these two strategies cannot agree and face each other with some bitterness. This often prevents the solution to the problem at hand. Because each side alone cannot solve many problems in today’s society by itself [CK14]. Direct state interventions fail due to the complexity of society and slow bureaucracy. Markets today are also often not in a position to “function,” for example, due to lobbying by large companies, existing complicated regulations, monopolists, and a predatory mentality among “elites.” We explained in Section 5.3 that prices in stock markets no longer contain information and that financial markets resemble a game of chance.

The share of the government spending ratio has changed in many countries in recent years. Often, Scandinavian countries are cited as models for modern welfare states. Journalists Adrian Wooldridge and John Micklethwait, in their book “The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State,” call these states “all-you-can-eat” states [WM15]. They say that the main task of politics in the next decade will be to redefine the state and find ways to halt the strong state growth of recent years (“Elephantiasis”). In many countries, Progressives generally want better social care provided by the state—hospitals, kindergartens, and nursing homes. Conservatives, on the other hand, want security, prisons, armies, and subsidies for large companies. In the language of the “political game” from Section 11.1, both “parties” use the same means for different goals and can form a “coalition.” To do this, they don’t even have to govern together at the same time; they can do it alternately, as in the USA. The state is simply expanded in different directions each time. Voters, on the other hand, have only their own well-being in mind and continue to vote as long as politicians promise them short-term benefits, such as earlier retirements, “more net from the gross,” or “free subway rides.”

Bureaucracies generally change much more slowly than profit-oriented organizations (see Section 5.5). Therefore, many changes resulting from digitalization have only been implemented in companies, but not yet in the authorities and ministries of states. Authorities face no pressure to change because of their funding through taxes. Many states spend disproportionately large amounts of money; for example, they employ only 15 - 20% of all workers but spend up to 50% of the GDP [DMW15]. According to Wooldridge and Micklethwait, states today face major problems, and it is questionable whether states can implement these changes. Voters might not be prepared for personal cuts, such as “tightening the belt,” as Chancellor Angela Merkel still called for in 2009. Instead, they then vote for the far-left or far-right.

But at least Denmark and Sweden are somewhat ahead of their time. Both went through economic crises in the 90s and reformed their states. In Sweden, for example, the education and healthcare systems were reformed [WM15].

Complex Politics

In many countries, most parties advocate “steering” the economy through politics, as in the days of mercantilism. For this reason, countless laws and regulations are enacted annually. The following quote illustrates this:

“Government’s view of the economy could be summed up in a few short phrases: If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it.”

Roughly translated, it means:

“The state treats the economy as follows: if the economy flourishes, it taxes it. If it continues to grow after that, it regulates it. If it then stops working, it subsidizes it.”

However, there are very different types of interventions with different effects and side effects. What should such interventions look like? Economist David Colander and management consultant Roland Kupers explore this question in their book “Complexity and the Art of Public Policy: Solving Society’s Problems from the Bottom Up” [CK14]. Their fundamental insight is as follows: state and market are not opposites, but a symbiosis that emerged through coevolution. They influence each other and have had to adapt to each other throughout history. On the one hand, the state can destroy markets through wrong policy, and on the other hand, wrong behavior in markets can force the state to intervene. Markets for hitmen or terrorism, for example, must be banned by the state if no other social norms can prevent their emergence.

Important: State and market are a symbiosis and emerged through coevolution.

Colander and Kupers call their system “Laissez-faire Activism”. In their ideal policy, as few “top-down” interventions as possible are made; society and the economy develop mainly “bottom-up.” The state only provides the framework (activism), and society does the rest itself according to its own ideas (“laissez-faire”). The state should be a midwife and not a controller [CK14]. It is policy-making while taking into account the properties of complex systems, game theory, behavioral economics, networks, ABM, economics, data, and data science. In short, a policy that requires the content presented in this book. This “complex politics” can unite the opposites of “top-down” and “bottom-up” described above. In the complex view, however, the story “I, Pencil” from Section 5.3 looks a bit different because the influences and services of the state must be considered [CK14]. For example, the trucks transporting the wood for the pencil drive on state-funded roads; the wood could only be cut because it is permitted under environmental guidelines; the food the lumberjacks eat must comply with food laws, and so on.

This is not to say, however, that these services previously performed by the state must really be performed by the state and not by private companies offering their services on a market. According to Colander and Kupers, in the complex view, besides “for-profit” companies, there can also be “for-benefit” companies already mentioned in Section 5.5. A “for-benefit” company sets a specific social goal to be achieved in its corporate charter, such as producing a cheaper drug that, for example, 90% of the population can afford even without financial assistance2.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts between Established and New

There are red and blue oceans, competition and innovation, globalization and technology, zero-sum games and non-zero-sum games. An innovative product often wins at the expense of outdated products. New industries win at the expense of established industries. An example is the company Kodak, which dominated the market for photos, cameras, and film until the 90s and at times had up to 145,000 employees. Although Kodak was itself a pioneer in digital photography and built one of the first digital cameras in 1975, the company “slept through” the development of digital photography and had to file for insolvency in 2012.

The innovative industry has already won the economic competition, so the established industry resorts to political means: lobbying and calls for “political debates,” as the President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz (SPD) did in 2015, for example. The SPD is a political party on the one hand, but also a business enterprise on the other, as it holds many interests in media companies, newspapers, and printing houses.

Important: Politics is interest representation. Politicians are not altruists who only optimize the common good.

In a market economy, the conflict between the old and the new is settled through the market. Customers decide what they buy. This also works in most cases without major political intervention. And if not, it is often enough to create a legal framework once. In the 80s, some people were dissatisfied with the food industry. Food was no longer natural enough for them. At first, these organic foods could only be bought in special stores called, for example, “Mother Earth.” Farmers decided to grow biological food, and traders decided to open retail stores for organic food. These people would be called “Bio-Entrepreneurs” today. To Peter Thiel’s question, they would have answered: “I believe that natural foods are healthier, taste better, and many people will also pay a slightly higher price for them”. The ability to found a company, own one’s own means of production, and decide for oneself whether to use biological or artificial fertilizer led to a great improvement in the food supply. The initiative came from the private sector, from individuals. The state followed only much later with “organic” seals and test labels, which in turn were often criticized as insufficient by private organic initiatives. Naturally, there were “battles” here too between the old and the new, and the established food industry first tried to push back against organic food or represent “organic” as unnecessary and unhealthy. But eventually, they jumped on the bandwagon.

Important: “Political debates” arise in a society with scarce resources when influence can be exerted on the distribution of these resources through politics.

Marxism

The work of Karl Marx (1818 - 1883) has many facets and has been interpreted in various ways. Generally, a distinction is made between the early Marx, who published the “Communist Manifesto” together with Friedrich Engels in 1848, and the later Marx, who published two volumes of “Capital” in 1867 and 1885. Because here, there are opposing and contradictory statements [Bla14, Des04].

The world at the time of Karl Marx was quite different. At that time, there wasn’t even electricity everywhere. It was still the era of the steam engine, not the internal combustion engine. In the year of Karl Marx’s death, Gottlieb Daimler developed the first single-cylinder four-stroke engine. Karl Marx used the word “productive force” for the entire technical and organizational knowledge of a society. And these “productive forces” have changed significantly due to technological development. His analyses can no longer be correct today. Because as explained in Chapter 9, the digital economy differs from the physical economy, and as explained in Chapter 4, knowledge has long replaced capital as the limiting production factor. Therefore, it is only natural that many parts of his work have been refuted by other scientists in the 130+ years since his death. This was the case with many other economists from that time as well. Eugen Böhm von Bawerk, for example, dealt with Marxian theory in 1896 in his work “Karl Marx and the Close of His System” and refuted the “transformation of labor values into market prices” [Bla14]. Ludwig von Mises investigated state socialism in 1922 in his book “Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis”. If all means of production are in state possession, there is no market with buyers and sellers for them, and therefore no market prices [Mis49]. However, the price is the foundation for the economy as an information system [Gil13]. No economic calculation is possible in monopolies. Then there is the knowledge problem of Friedrich A. Hayek: in a centralized planned economy, all knowledge would have to be centralized. This is not feasible [Hay48]. And economics has evolved and—as described in Chapter 5—faces another transformation with complex economics.

The economist Meghnad Desai is of the opinion that Marx has always been misunderstood. With his book published in 2002, “Marx’s Revenge: The Resurgence of Capitalism and the Death of Statist Socialism,” he caused a stir in certain circles [Des04]. Desai is no stranger in Great Britain as a politician for the British Labour Party and as a former member of the executive committee of the Fabian Society, a British socialist society. He published several books on Marx and Lenin in the 70s and 80s.

According to Desai, Karl Marx’s name was abused by most politicians, sometimes even before his death. They only used his name to push through their own interests. Karl Marx would have approved of neither social democratic parties, the October Revolution of 1917, nor the Soviet Union. Desai writes that Karl Marx’s answer to the question “should the state steer the economy or the market?” would shock many. Because his answer would be the market! He was a “champion” of free trade and against customs barriers. Today, he would not be an anti-capitalist opponent of globalization, nor a supporter of regionally restricted markets, as many today’s TTIP opponents are. He would be against central planning of the economy and was also no supporter of a socialist state. Of course, Karl Marx was no friend of capitalism, but he studied it for decades. Karl Marx believed he had discovered a “dynamic” according to which capitalism would overcome itself and automatically lead to communism. According to Karl Marx, however, capitalism will only disappear after it has unfolded its full potential.

Capitalism has reached its full potential for a product when it can overcome scarcity, i.e., when the product exists in abundance. Abundance is also a promise of the Singularity. If there are intelligent computers that can improve themselves, then these can also invent robots and automatic factories that can produce all goods very cheaply. After the Singularity, most things would therefore exist in abundance. Management consultant C. James Townsend connects the two ideas of Singularity and Socialism in his book “The Singularity and Socialism: Marx, Mises, Complexity Theory, Techno-Optimism and the Way to the Age of Abundance” [Tow15]. According to Townsend, today’s socialism has completely forgotten this “dynamic” of Karl Marx, this evolutionary vision, and has gotten bogged down in interventionist politics. In doing so, in his opinion, the development of capitalism was hindered, and the entry of communism postponed to a later date. According to Townsend, after the Singularity, a system will come that overcomes both “socialism” and “capitalism” simultaneously. The economy after the Singularity has completely different laws. Of course, this raises many questions, such as who in such a society owns the means of production. However, the original demand of Marxism—“from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”—can only work with non-scarce goods, because as soon as there is too little of something, conflicts of interest arise, and people would have to be “common-good optimizers” to solve these conflicts.

By the traditional “Left,” however, Karl Marx is interpreted very differently today. Karl Marx is used today by many politicians and parties because the state does not appear in his analysis, and they can use Marx to push their interests against some parts of the economy. It is strange that Leftists in Germany decry companies like Google and Facebook as “capitalists” [Sch15], while they leave the German industry subsidized with tax money alone or even support it, such as automobile and chemical companies.

Work and Jobs

Knowledge and Service

One thing is certain: new technologies will have profound changes in the world of work. In the information and knowledge age, one can simplify the distinction between the following two types of professions [Dru94, BA14, TM14]:

- Knowledge workers for complicated and complex systems

- Service workers for simple systems

A knowledge worker today often works at a PC and requires prior knowledge and expertise for their work. Examples include tax consultants, insurance agents, lawyers, journalists, doctors, computer programmers, or managers. These are professions for complicated and complex systems, and the knowledge is usually imparted in a degree or longer training. A service worker, on the other hand, usually only operates simple systems and requires only rudimentary training for it. In some cases, these jobs are so simple that they require no proper training at all, such as helpers in supermarkets, warehouse workers, or at a telephone hotline.

Which jobs are particularly threatened by technology?

In the preceding chapters, we have become acquainted with data science, artificial intelligence, and digitalization and can now better assess these technologies. From behavioral psychology in Section 3.2, we know that humans are boundedly rational and use System 1 heuristics for pattern recognition and System 2 for trying out all possibilities. In short, there is “heuristic work” and “systematic work”. From Chapter 8 on artificial intelligence, we know that computers can master both types of work. Fifteen years ago, it was still believed that computers could only do “systematic work” because the PCs available then were still too weak for larger multi-layer neural networks [BA14]. Today, with self-driving cars, it is clear that computers can also take over heuristic work. Since technological development is on the second half of the chessboard (Section 9.1), more complex tasks will also be performed by machines in the future. However, one must also consider that self-driving cars did not appear “surprisingly” on the scene, as intensive research has been conducted on them for about 10 years. Most technical changes announce themselves far in advance.

Computers are generally not good at asking questions; they have no creativity, cannot think outside the box, and have no ideas of their own [BA14]. Therefore, professions requiring these abilities also cannot be replaced by computers. KIs also cannot flexibly handle the meaning of languages and have difficulty integrating news into their knowledge databases on their own. The creative handling of knowledge and news will therefore remain reserved for humans for longer.

All activities, on the other hand, that require relatively static knowledge are threatened by automation. Interaction with people in telephone hotlines is already partially automated. These dialog systems will improve in the coming years. Simple knowledge work will be performed by computer programs, such as the automatic translation of non-literary texts.

Regarding robots, the future will depend on whether it will be possible to build robots that can, for example, move freely in an apartment without damaging the furniture and how much electricity they need for it. For example, it is still a very long way until a robot can dust in an unfamiliar apartment without damaging objects. Larger robots, however, will continue to find their way into everyday life, for example, as cooks in self-service restaurants. Therefore, in the case of service work, it is not yet clear which can be automated and which cannot. Precise manual tasks, such as picking up and folding a towel, are still difficult for robots at the moment [BA14].

Substitution and Augmentation

When using new technology at work, there are two possibilities [BA14]:

- Substitution: the technology replaces human labor

- Augmentation: the technology supports human labor

For example, a self-driving train replaces a locomotive driver. An autopilot for an airplane, on the other hand, supports the pilot. Mixed forms can also occur: if, for example, a robot can support the productivity of a worker, fewer will be needed overall. Some workers are therefore replaced, and the remaining ones supported.

Now, humans are very capable of learning and can replace or augment their own Systems 1 and 2 with artificial Systems 1 and 2. In “freestyle chess,” a professional chess player can use a chess program for support and is generally better with it than the chess program alone [BA14]. A statisticer can achieve significantly better results with data mining and data science. Architects have been using CAD systems for their designs since the 90s. Most people use Wikipedia, online dictionaries, search engines, navigation systems in cars, SMS, emails, etc.

Human labor is usually supported by technical inventions. Work itself has never run out. But some people have always feared this with technical inventions [Haz88]. As long as the world is not perfect, there are things to be done, and thus work is available.

The Skills Shortage

The ever-faster technological change also creates irritations in the economy, such as the skills shortage often cited in the German press. The education system is not in a position to adapt every two years to the new products of the computer industry. Many of the tools and software tools used today are not even ten years old. Hadoop, for example, celebrated its tenth birthday in 2015. For many employees, it is not worth training for a new technology or tool in the short term if the effort is not reflected in the salary and one has to learn anew in 3 years. Given very rapid technological development, a skills shortage cannot simply be remedied by calling for “education,” because many skills are already outdated by the end of that education. Within the period of a university degree of three to four years, a great deal has already changed in computer science, for example. Therefore, a computer science degree is usually more abstract. One learns the basics and “learning” so that one can later train in current technologies. Many companies seemingly still have to learn to adjust to this development. They believe that society must produce ready-to-use workers that companies can then simply pick like low-hanging fruit. In reality, with rapid technological change, this is no longer possible, and companies must transition to training their employees themselves or bringing in external specialists.

And Politics?

How should politics behave regarding “disruptive” changes? Let’s take self-driving cars as an example. Should politics ban them to protect the jobs of taxi drivers, bus drivers, and train drivers? One must weigh the advantages and disadvantages for the drivers and for society in each case. With today’s technology, the result usually is that progress cannot be stopped for long. Halting technology is usually associated with disadvantages for the domestic economy [BA14]. In Great Britain at the beginning of the 20th century, the maximum speed of newly emerging automobiles was limited to 6 km/h so as not to present too much competition to horse-drawn carriage drivers. This was an opportunity for the automobile industry in other countries because they could develop cars without these limitations.

When workers are replaced by technology, one can ask whether the knowledge of the workers can still be used in “augmenting” systems. Can the worker’s productivity be increased again with computer assistance so that hiring becomes profitable again? This thought was first held by Frederick Winslow Taylor, who was discussed in Section 4.2. Or can a worker use their knowledge elsewhere? If a taxi driver is now replaced by a self-driving car, the driver can perhaps use his knowledge of the city as a tour guide. He might know the best restaurants, and business travelers would be grateful for tips and are also willing to pay a little more for them.

A deeper discussion, however, would go beyond the scope of this book. Most serious futurists think, however, that the positive aspects of technical progress will outweigh the negative aspects [DMW15, BA14].

Important: As a rule of thumb: the more independent thinking is required and the more complicated a task is, the less likely it is to be automated in the near future.

Today’s school system, however, trains memorization, “functioning,” and the uncritical adoption of groupthink. In the future, however, ideas, problem-solving, pattern recognition, “computational thinking,” and communication will be important in the world of work. It is perhaps no coincidence that the founders of Google, Amazon, and Wikipedia come from Montessori schools and not from the state education system [BA14].

If many people were to really become unemployed, many economists are also prepared to discuss new work models and social security systems, such as a universal basic income [BA14]. However, such a basic income is a major “top-down” intervention in a complex system. It is a massive intervention in the relationship between supply, demand, and the price of human labor. It is therefore not foreseeable what the consequences of such a basic income would be.

Monopolies and Patents

In Section 9.10, the “winner-takes-all” characteristics of many digital markets were explained. If a company offers a superior product that the competition cannot offer or only offers at a higher price, a natural monopoly can arise. A natural monopoly is not bad because it reflects the wish of the customers. It is different with an artificial monopoly: in an artificial monopoly, a company alone can offer a product. Customers are forced to buy this product from this company. Therefore, the company can artificially increase prices, tighten supply, worsen quality, and keep customers “on a leash.” This is why artificial monopolies are generally viewed very critically. Strangely enough, however, only when it is not an artificial monopoly for the state.

Here we must remember the two perspectives of the supply side and the demand side from Section 5.3: Yin and Yang. From the perspective of demand, in a market economy, there is ideally competition on the supply side. Companies are in competition with each other, and customers can choose inexpensive products. From the perspective of supply, however, it makes sense to strive for a monopoly, as Peter Thiel also clearly states as the goal of a company [TM14].

For the economy to function, there must be a healthy balance between monopolies and competition. If other companies can simply copy a company’s products, then the development of the product is no longer worthwhile for the company (“piracy”). But it also becomes dangerous if the formation of artificial monopolies is too easy. Because then there is no progress and many legal disputes over trivial patents.

In an information and knowledge economy, in which information and knowledge are traded as economic goods, it is necessary to protect “intellectual property.” Here, one distinguishes between the following possibilities:

- Trade secret

- Copyright

- Patents

- Trademark

The original method of keeping information secret is the trade secret. The recipe for Coca-Cola, which has not yet been published, can serve as an example. However, this does not work for machines that can be disassembled and “re-engineered.” Delivered software can also be analyzed.

With a copyright, the production of a copy of an intellectual work can be prohibited, such as of a book, music, or film. Thus, with a copyright, a 1-to-1 copy is prohibited, and the investment of the creator is protected. This cannot lead to monopolies.

A patent, on the other hand, is applied for at a patent office and does not apply to a specific work, but to a method or a technical pattern. The companies Apple and Samsung, for example, fought many lawsuits because Apple had a patent on a “mobile phone with only one button.” With the help of this patent, Apple prevented Samsung from bringing comparable products onto the market. Patents can therefore lead to monopolies and be a threat to competition.

Today’s patent systems lead to downright “patent wars” between large companies. Smaller companies, in particular, are unable to keep up and are pushed out of the market. Therefore, today’s patent systems need to be reconsidered and made fairer [Rid10, Hin13].

Data Protection and Privacy

Data and Data Protection

Data is an important “raw material” for information. Information reduces uncertainty and thus leads to better decisions. This affects the economy, as well as the institutions of the state and science.

Now, not all data is equal. Some data allows for conclusions about the person who generated this data, reveals embarrassing details, or offers opportunities for blackmail. Here, the proverb “Knowledge is power” applies. In the wrong hands, knowledge can become very dangerous! On the other hand, some data is essential for the provision of services. A telecommunications company must know which cell a mobile phone is in so that it can route signals to the correct transmitter mast. Knowledge is contained in data and is the most important element in the knowledge society and economy. Without data, there can be no knowledge.

Around the year 2000, when the Internet and all the social networks were new, everyone was initially enthusiastic. Over the years, however, concerns arose: Where is the data actually stored? Who can view it? What about data protection? What about privacy? The fact that initial enthusiasm fades and gives way to a critical view is actually the case with all new technologies. When people were still poor farmers before industrialization, they welcomed industrialization and initially ignored the side effect of environmental pollution. When sufficient prosperity was then available, one began to worry about pollution and started to improve it. This is actually the normal way of the market economy. Companies develop products, customers try them out and give feedback. Thereupon, companies improve their products, and so on.

Software developers also had to gain much painful experience here, for example, how they can make their products more secure, how data can be transmitted in encrypted form and stored securely in databases. There is always a race between software developers and the hackers who try to find security vulnerabilities. But that is the same in the physical world with criminals, because banks are also robbed, for example.

The discussion about data protection is often very difficult because the term data is so general. Is it personal data, such as address and place of residence, or user data, such as games purchased? Is it camera images from a surveillance camera in a public space or on private property? Is it an audio recording of a conversation in which the participant did not know it was being recorded?

Privacy

It is not possible to give a simple answer to all these cases because very many different views and legal concepts are touched upon here. A statement often made by critics in the media is “computers threaten privacy”. But what does that mean exactly? What is privacy, what is private? If these questions are not easy to answer, what then should a “right to privacy” be?

The fundamental problem is that there is no unambiguous definition of “privacy”. American law professor Daniel J. Solove investigated the various definitions of “private” in his work “A Taxonomy of Privacy”. He concluded that “privacy” cannot be used as a basis for legislation (“privacy is far too vague a concept to guide adjudication and lawmaking”) [Sol06, PF13].

But one can generate political sentiment with it, similar to the word “social.” After all, everyone can define for themselves what they understand by “private” at the moment.

Important: Because there is no clear definition of “private,” any intervention, regulation, or ban can be justified with the “right to privacy.”

On a public street, one is precisely in public and not in “privacy.” If a camera films this street, can one then insist on a right to “privacy in public”? If someone enters their data into a social network so they can play games there, and this data is stored on the social network’s servers, is it still “their” data? After all, they are using the network’s servers.

All these questions are not easy to answer because, in the end, the word “private” is not clearly defined. This problem carries over to discussions about “data protection.”

The most important thing is that people learn certain basic rules for the safe handling of data. That they do not store important data in social networks at all. These don’t have to know everything. Companies, on the other hand, should make their systems as secure as possible. There are various data protection seals and legal requirements here.

It is very important, however, that not only critics, lawyers, and large companies participate in the discussions. Data protection, like environmental protection, is a cost factor for companies. Most companies today realize that important personal data should be stored in encrypted form and systems made as secure as possible. But under certain circumstances, complicated measures are necessary that make the systems more expensive, so that for cost reasons not all data can receive the same protection. Here, small and medium-sized enterprises must also be consulted.

One should also be able to elect data protection officers through grassroots democracy. Otherwise, there is a danger that these officers become a pawn of political interests if they can be appointed by the parties.

Somewhat outside the topic of this book is the question of how cameras in public spaces should be handled. The smaller the cameras become, the more intensive the discussions will likely become. If someone wears glasses with a camera that automatically performs facial recognition and searches for information about that face on the Internet and can display the information found (similar to Google’s glasses), then anonymity no longer exists. Humanity then really lives in a global village where everyone knows everyone. City dwellers often perceive this as a threat, while rural populations and small-town dwellers know it from everyday life.

Economy and State

In data protection, one must distinguish between the following groups:

- Companies

- Good: Require data only for service or product creation

- Bad: Espionage companies, detective agencies

- States and their intelligence services

- Gangsters, hackers, cyber-crime

The normal case is a company that offers a service or manufactures a product and processes data for this purpose.

Important: The handing over of data to companies is voluntary.

No one is forced to enter data into a social network. One can also “opt out” and be a “drop out” and declare this a fashion trend or a good lifestyle.

Unfortunately, there will always be companies that abuse the trust of their customers. However, “good” companies will try to improve data protection and offer, for example, encrypted transmission. Companies are sometimes forced by governments by law to release certain data. Telecommunications companies in Germany, for example, are obliged to “data retention” (Vorratsdatenspeicherung). Here, there were many accusations against many companies in the USA, such as Google and Apple, because they were said to have supplied data to the American NSA. Here, many critics do not know that a company has no possibility of political resistance other than legal action, lobbying, and media work. Companies cannot be freedom fighters because they would then simply be closed. Critics often interpret this as support for a political system. But companies can only leave a country; for them, the rule is: “like it or leave it”. The lack of protest regarding censorship on Facebook in Germany has also shown that even the “Left” is not fundamentally against censorship. Facebook, on the other hand, can only bow to the governing SPD or leave Germany.

The second group is formed by states, their intelligence services, and associated organizations. here, the individual cannot freely decide which data they give to whom. The state justifies data retention, for example, with the fight against terrorism and other crimes. A problem becomes visible here: on the one hand, many people want to entrust the state with important tasks because they do not trust “the market” or because they are against the profit-oriented economy, but on the other hand, they lack the possibility to control the same state themselves.

Important: Many people are willing to transfer power to the state but have so far found no way to prevent the state from abusing this power.

The NSA, CSEC, GCHQ, BND, and whatever they are called, are actually all democratically legitimized by their voters. The majority of people in the respective countries have agreed to it. Now some will say, but the NSA is not a German secret service; couldn’t they be forbidden from spying in other countries? Yes, then the Federal Intelligence Service (BND) would also have to be forbidden from spying in other countries. Does any party in Germany have that in their party program? Since states have existed, there has been espionage, intelligence services, and surveillance. This problem has always existed and has only returned to the spotlight through technological development.

If a state wants to monitor the communication of its citizens, then it must make agreements about surveillance with all communication companies. From the perspective of the state, this is easier the fewer communication companies there are. The state therefore has an interest in dividing the market among as few companies as possible. Here, large communication companies can thus enter into a coalition with the state by designing regulation so that large companies get rid of their smaller competitors [Wu13].

Important: The fewer communication companies there are, the easier surveillance is for the state. The number of companies can be reduced through regulation.

For the population, the only consolation remains that data can be encrypted. At least as long as that is not forbidden. With encryption, data can only be decrypted with the correct password. Several states have already demanded that their intelligence services need a kind of universal password, a “backdoor,” so that they can fulfill their tasks in fighting crime. There is a tradeoff here between security and the freedom of the population.

Important: Encryption must remain allowed without a “backdoor” for intelligence services.

For open societies and democracies, the Internet is a blessing; for dictatorships, however, it is a surveillance instrument. Google CEO Eric Schmidt and Google employee Jared Cohen go into more detail on the role of companies and states in the political sphere in their book “The New Digital Age: Reshaping the Future of People, Nations and Business” [SC13].[]{#_Ref440963974 .anchor}

-

By “Leftists” in this book, the party “Die Linke” is not meant. ↩

-

At this point, of course, the people of the unrestricted vision of Thomas Sowell cry out “and what about the other 10%? That’s inhumane!”. Of course, it would be good if everyone could afford the drug, but it is not possible to produce a drug for free. When considering costs, one must make a tradeoff. It is better to have a drug that 90% can afford than none at all. The other 10% must then be provided, for example, by private organizations, donations, or through state aid. ↩