Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

The Future

Utopias and Dystopias

Predictions are difficult, especially …

The Danish physicist Niels Bohr once said, “Predictions are difficult, especially when they concern the future.” And he was absolutely right. One can only have uncertain knowledge about a complex system because the agents within that system can change their behavior. The further one tries to look into the future, the more uncertain the prediction becomes, as the number of changes grows proportionally. If you don’t even know what the agents will do in the next time step, you certainly cannot know what they will do in the one after that. In statistics, historical data is often used to “extrapolate” the future. This works wonderfully for simple and complicated systems, provided you have a sufficiently long history. However, it is the changes in complex systems that make predictions so difficult.

The psychologist Philip E. Tetlock has been studying decision-making and forecasting since the 1980s. Together with journalist Dan Gardner, he describes the difficulties of accurate prediction in the book “Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction” [TG15]. Using an internet platform, the two investigated how well a crowd of volunteers could make predictions. One result of this study is that well-known “experts” in the media often predict no better than chance. We mentioned in Section 2.6 that complex systems require special techniques. If these are taken into account, somewhat better predictions become possible.

Important: Reliable predictions over a long period are highly unlikely in complex systems.

One can clarify this with an example. Let’s transport ourselves 30 years back to the year 1985. Back then, the film “Back to the Future” was released, and the Warsaw Pact still existed. Some economists at the time even believed in the superiority of the socialist planned economy. Even Perestroika, which triggered the major changes, did not begin until 1986. There was little to see of digitalization and the Internet. Therefore, predictions made in 1985 for the year 2015 simply could not be correct because the world developed in a completely different way.

But why do we see so many predictions in the media then?

Because they can be used for various purposes. Some predictions serve specific political groups to encourage people to take certain actions or to accept specific legislative changes. There are two different strategies here: reassuring, such as “Pensions are safe,” or alarming, such as old-age poverty, the environment, and crises. Insurance companies and banks use forecasts of price developments to sell their products or to reassure their existing customers. With predictions, one must therefore always question the interest of the creator. What do they want to achieve? Who benefits from the prediction?

Utopias and Dystopias

Many people have already given thought to the future. These thoughts can be divided into two groups: In a positive utopia, the future is better than the present, or at least no worse; in a dystopia, a negative utopia, the future is worse. Humans apparently tend to concern themselves more with dangers than with something pleasant. Indeed, there are significantly more negative than positive utopias. Following the motto “Good news is no news,” positive stories are harder to sell.

Examples of negative utopias include George Orwell’s “1984” (1949), Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451” (1953), or Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” (1932). Then there are many films like “The Matrix,” “Terminator,” “Brazil,” or “Soylent Green.” In most books or films about artificial intelligence and robots, they eventually become “evil” or are used by “evil-doers,” and the protagonists must defeat these malevolent machines.

Even in the “serious” humanities, there are many negative utopias: Oswald Spengler wrote “The Decline of the West” in 1918. Through the “Frankfurt School” surrounding Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse, originally positive Marxism was twisted into the negative “Critical Theory,” according to which capitalism is “to blame” for absolutely everything [Her07]. For the late Karl Marx, capitalism was still supposed to develop “to its end” and then lead almost automatically to socialism [Des04]. In France at the end of the 19th century, there was the “fin de siècle” movement (“end of the century”), which addressed “cultural decay.” Even in today’s media, many threats are portrayed and anxieties about the future expressed: diseases and epidemics, environmental problems, limits to growth, and threats from technical developments. There seem to be few people looking optimistically into the future.

But for reassurance, it can be said that a very large portion of these predictions is most likely wrong because complex systems cannot be predicted over a long period, as the agents adapt. And in our world, the agents are humans who learn and change their behavior.

In 1966, for example, the novel “Make Room! Make Room!” (New York 1999) by Harry Harrison was published. The author tried to look 33 years into the future. The book remained relatively unknown, perhaps because the author had miscalculated his prediction so significantly. In the book, New York in 1999 has a staggering 35 million inhabitants, most of whom live in mass poverty because food and drinking water are scarce. According to Wikipedia, the author explained it as follows1:

“In 1950, the United States, with only 9.5 percent of the world’s population, consumed 50 percent of the earth’s raw materials. This percentage is constantly rising, and at the current growth rate, within fifteen years, the United States will consume over 83 percent of the annual production of all the earth’s raw materials. If the population continues to grow at the same scale, this country will require more than 100 percent of the earth’s raw materials by the end of the century if the current standard of living is to be maintained.”

Here, the author simply extrapolated the values of the time into the future and failed to consider various dynamics. On one hand, there is technological development, and humans now produce goods in a more resource-efficient manner. On the other hand, demographic development took a completely different path. Since the late 60s, the invention of the “pill” ensured that humans did not multiply as before. This created the “birth slump” (Pillenknick). But at least the author admits his naive “extrapolations” by saying “at the current growth rate” and “if the population continues to grow”. But the world is dynamic. In a market economy, prices rise when raw materials become scarce. Consequently, people think about which alternative raw materials they could use. An example of this is the rising oil prices in the 70s and 80s. People then tried to find substitutes for expensive oil and gasoline. People started riding bicycles and using trains, and finally, today, we even manufacture electric cars.

A large portion of the predictions published in the media today suffers from these extrapolation errors. One does not get a correct picture of the future by simply continuing the present linearly and ignoring possible changes.

Important: Only a few predictions so far take the findings of complex systems into account.

The Framework Conditions

What do the Economic Advisors Say?

Economic advisors Richard Dobbs, James Manyika, and Jonathan Woetzel describe their assessment of the future global economy in their book “No Ordinary Disruption: The Four Global Forces Breaking All the Trends” [DMW15]. They believe that the world is facing major changes and that everyone, especially managers and politicians, must “reset” their intuitions. Remember Systems 1 and 2 from behavioral economics? Dobbs et al. mean to say that the complex system of the economy has changed and that the heuristics learned by heart by System 1 are no longer correct. These must now be explicitly unlearned to adapt to the new situation.

The global economy is no longer what it once was. As an example, Dobbs et al. cite the Indian mission to Mars. In September 2014, the “Indian Space Research Organisation” flew a spacecraft into Mars’ orbit. And it did so for the equivalent of 74 million US dollars. The Hollywood film “Gravity”, on the other hand, had a budget of 100 million US dollars. This means India now has significant comparative advantages relative to the United States and is thus no longer a “developing country.” Speaking of “developing country”: Peter Thiel makes a very profound remark about this. The word “developing country” suggests that there are also “non-developing countries,” i.e., “developed countries.” This creates the illusion that countries like the USA and the EU nations are “finished” and do not need to develop further [TM14]. If this illusion truly exists, then companies in these countries stop searching for blue oceans. A “developed” country does not need innovation, they think. But as a result, they lose their “competitive advantage,” which leads exactly to the effects perceived as negative during “globalization” in the West: companies relocate production for cost reasons. As long as there is progress, “developed country” is a misleading term. India, in any case, is the fourth country on earth to have achieved a Mars mission and is now ahead of many other countries in that regard.

According to Dobbs, Manyika, and Woetzel, the world will be strongly changed in the near future by the following “forces” [DMW15]:

- Globalization and Urbanization

- Demographic Changes

- Acceleration of Progress

- Connectivity

These four “forces” interact with and reinforce each other. They lead to changes in almost every market and almost every economic sector. The economy is becoming more dynamic. Predictions are usually difficult enough, but according to Dobbs et al., they will become even more difficult due to these four “forces” [DMW15].

Globalization and Urbanization

In the coming years, many people will be integrated into the global economy [DMW15]. Most inhabitants in so-called “developing countries” previously did not even have a landline telephone. They only became reachable with mobile phones. It is estimated that between 1990 and 2010, one billion people escaped poverty and were able to enter the global “consumer world.” Another two billion are expected to follow by 2030. Through smartphones and mobile internet access, communication possibilities for many inhabitants will continue to improve: they will become part of “collective intelligence”.

These people need work, and therefore production is being outsourced to these countries. “Globalization” will continue. Jobs are already being moved from emerging countries like China to even “cheaper” countries. In China, robots are already being used in production because human labor has become too expensive [BA14].

Secondly, there is still a relatively high proportion of rural population in emerging and developing countries. With integration into the world economy, fewer people in many countries will work in agriculture and will move to the cities. According to Dobbs et al., there will be a wave of urbanization. The advantages of cities still outweigh their disadvantages [Rid10]. Cities shorten communication times, lower the costs of searching for new labor, and are centers of communication and encounter. Humans rely on social cooperation because of the division of labor. A higher division of labor increases the productivity of a society. Previously medium-sized and unknown cities, such as Kumasi, Foshan, Porto Alegre, or Surat, will become important metropolitan and industrial centers. Each of these cities forms a metropolitan area with more than 4 million people, and according to Dobbs et al., each will contribute more to economic growth in the future than Madrid, Milan, or Zurich [DMW15].

Western companies must first get to know these rapidly changing countries. Previously, 70% of the global gross national product was generated in the “developed countries” and the large cities of emerging markets. For 2025, it is estimated that only 33% of growth will take place in the “old” world.

Demographic Changes

In almost all countries, the composition of the population will change, and the proportion of elderly people will rise [DMW15]. In 2013, 60% of the world’s population lived in countries where more people die than are born. In Western countries, there is the “birth slump.” In China, for a long time, only one child per marriage was allowed. This problem is now called the “4:2:1 problem”: each adult child must care for two parents and four grandparents. By 2030, according to current estimates, the number of globally available workers will have fallen by one-third [DMW15]. This “aging” will challenge the social systems of welfare states. This means fewer young people are working and more elderly people are in retirement.

Therefore, the “productivity” of the working young people must be increased. And for this, in turn, innovations are required. These are certainly possible with current progress, provided that progress is not “politically” prevented.

The Disruptive Dozen

As discussed in Section 9.1, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee identified the following three factors: digitalization and connectivity, exponential growth, and combinatorial innovations [BA14]. Through the Internet of Things (which will be explained in Section 10.4), the number of digitized processes and information will increase significantly. Connectivity will increase. Exponential growth in the number of transistors is expected to continue until at least 2030. The number of people involved in product development and the productivity of these people will rise, so the number of combinatorial innovations will also increase. Together, these three trigger the “Second Machine Age.”

But which technologies will this mainly affect? Dobbs et al. consider the following twelve technologies to be particularly important for the next decade (until 2025) [DMW15]:

- Building Blocks

- 1 Life Sciences: Genomics

- 2 Materials Science: Nanomaterials, smart materials

- Energy Sector

- 3 Better energy storage: Accumulators, batteries

- 4 New extraction possibilities for oil and gas (“fracking”)

- 5 Renewable energies

- Machines

- 6 Robots

- 7 Self-driving vehicles

- 8 3D printing

- Information Technology (IT)

- 9 Mobile Internet

- 10 Internet of Things (IoT)

- 11 Cloud services

- 12 Automation of knowledge work (Big Data, Data Science, AI)

Each of these twelve technologies has the potential to replace current existing technology and is therefore called “disruptive”. Dobbs et al. therefore call these twelve technologies the “disruptive dozen”. Half of this dozen is occupied by information technology, as robots and self-driving vehicles also belong to IT. Engineers can build robots quite well by now, but computer scientists cannot yet control them intelligently enough.

Information technology forms the “brain” with Big Data, Data Science, and AI, and the “nervous system” of the economy with the Internet of Things.

The Brain: Big Data, Data Science, and AI

The development of computers has—as explained earlier—arrived on the second half of the chessboard. The leaps are becoming larger. But findings from Artificial Intelligence show us that they will not be quantum leaps. Technology will get better and faster, and larger amounts of data from very many sources will be processed. Over time, increasingly complex decisions will be automated. But there will be no “wonder computer” that suddenly becomes more intelligent than a human and wants to take over world dominance.

However, there will be progress, and in the next five years, systems will be developed that are not yet considered possible today. It can be assumed that by 2020 there will be self-driving cars, although they will not yet be allowed in all countries. Kitchen robots will be able to prepare meals (in specially designed kitchens, not in every kitchen) after someone has cooked the dish for them once. Computer systems and robots watch and can imitate the demonstrated behavior (in specific areas of application). Computer systems will also master natural languages and, in sub-areas, enable automatic translation of spoken language. Someone speaks in English to someone in German over a phone, and both hear the statements of the other in their own language. This will initially be of poor quality but will slowly improve. There will be diagnostic systems to support knowledge-intensive work, such as in medicine or law [CM16].

And as described in Chapter 7, Data Science itself is not intelligent, but a tool with which intelligent people try to find the knowledge present in data. Intelligence resides in the Data Scientists who combine and deploy these algorithms. Here too, there will undoubtedly be progress, but not the feared “omnipotence of computers.” The horror scenario “computers know everything about us” will not become reality with today’s technology and today’s progress. Computers themselves cannot “know”; they can store information. “Knowledge” is information that can be applied by humans. Computers can only process symbols whose meaning they do not truly understand. They process only the syntax and not the semantics.

With a word like “Hamburger,” humans only know from the context whether a food item or a person is meant. Computer scientists are working on a “Semantic Web” where every word has information about its meaning attached. This process is very labor-intensive and also increases the cost of creating texts. Perhaps a semantic database can be created here using crowdsourcing. Initial techniques have already been developed, such as the “Resource Description Framework” (RDF), with which “things” can be precisely defined in a formal language, or the “Web Ontology Language” (OWL), with which ontologies can be created. Humans possess “common sense,” for example. Every person knows the properties of the physical “space” around them. Everyone knows that the opposite of “up” is “down.” A person can interpret phrases like “in front of the garage” or “behind the refrigerator.” In an ontology, this basic spatial knowledge can be formulated so that it is available as background knowledge for a computer. Without this “semantic” information, a computer does not “know” what it is doing. But formulating this knowledge, creating these “ontologies,” is associated with a great deal of work because it is a type of “programming” and “logical formulation.” Therefore, there will be no computers with “common sense” for the time being.

The Nervous System: The Internet of Things

The Internet Today

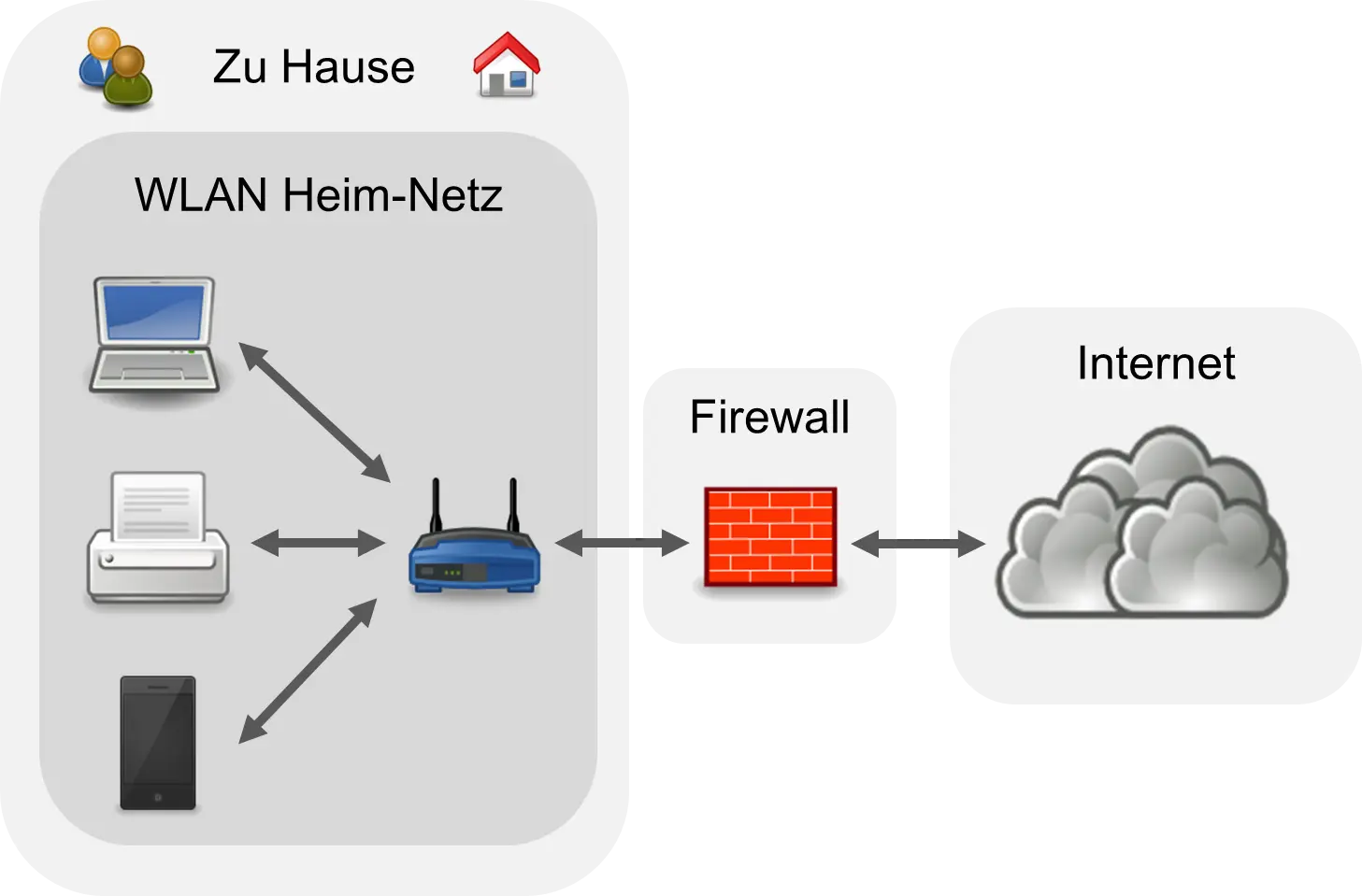

So far, only “larger” technical devices have been connected to the Internet, such as smartphones, tablets, laptops, PCs, televisions, and possibly light switches. One could call today’s Internet the “Internet of people and large devices.” Currently, a private network looks something like the following diagram:

Most people have a DSL connection to the Internet and a WLAN (“wireless local area network”) connects the devices in the house. Most have a combined device that is both a DSL modem and a WLAN router. What some do not know is that the DSL modem has a so-called firewall. A firewall is a security mechanism with which “packets” from the Internet can be checked and filtered out. The firewall prevents “hackers” from accessing the devices in the household from the outside. Such a firewall can be configured so that only certain connections are permitted or only the truly required “services” are let through.

This firewall is often forgotten when critics of artificial intelligence describe the dangers of AI drastically. Some critics then design a scenario in which an AI could reach and control all technical devices. And that is exactly what is not possible because of these firewalls.

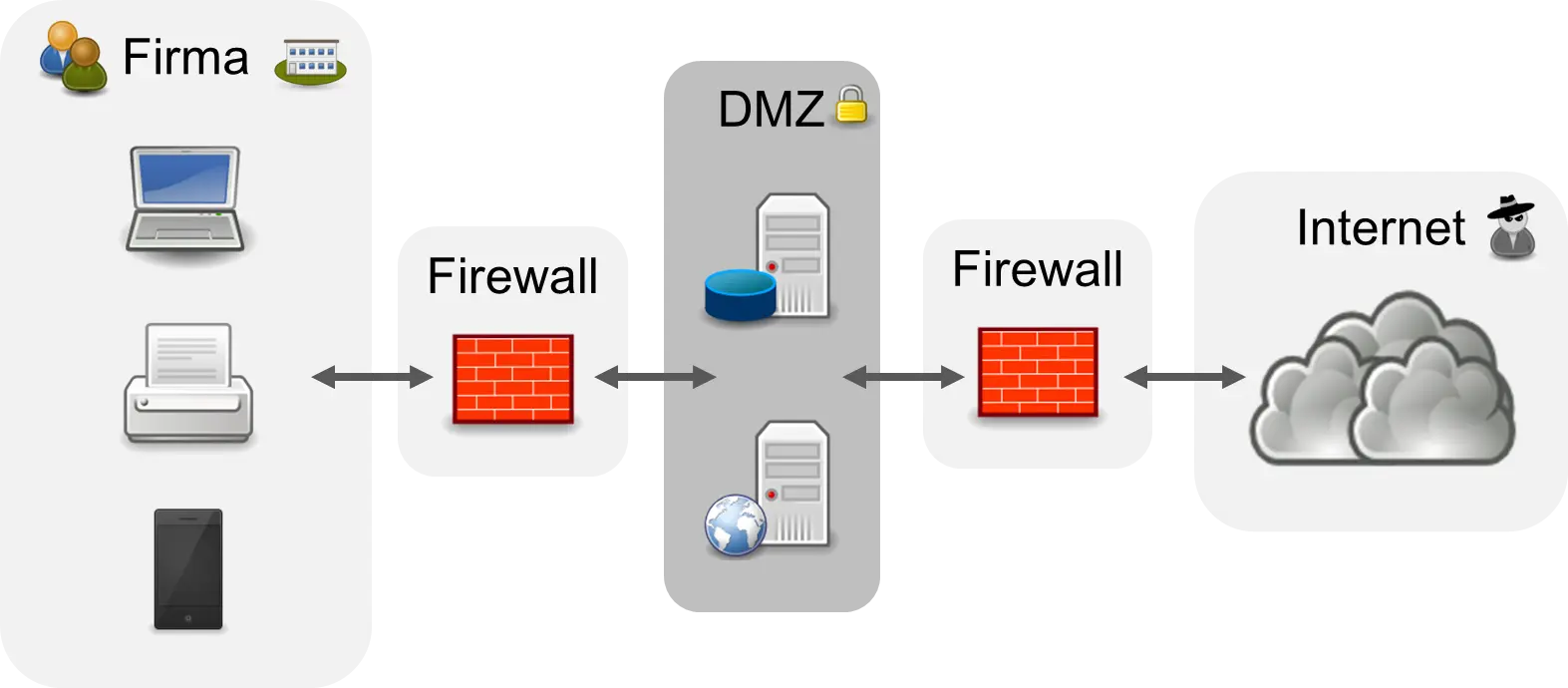

In corporate networks, even more importance is placed on security, and one often finds a so-called “demilitarized zone” (DMZ), which is protected on all sides by firewalls [Don11]. In the following figure, the corporate network is protected from the DMZ by a firewall, and the DMZ is protected from “hackers” on the Internet by a firewall.

Inside the DMZ are the computers for the services to be protected and the data to be protected. Direct access to the servers from the outside and from the inside is no longer possible. The corporate network is “isolated.” System administrators usually monitor the log files of the firewalls semi-automatically. Unusual access is investigated by the administrators. As a rule, today’s companies are well protected against attacks from the Internet. An artificial intelligence cannot achieve more here either, especially since “hacking” also requires creativity, and it is still completely open whether “creative” AIs will ever exist.

The Internet of Things

In the Internet of Things (IoT), all “things” that can send or process information are to be connected to the Internet. It is the information-technological recording of the physical world. The beginnings of the Internet of Things are already here, as one can already connect the following devices to the Internet [And13]:

- Body scales that send weight via WLAN to a website for evaluation

- Light switches controlled via WLAN

- Motion sensors that, for example, turn on the light when motion is detected

- Parcel tracking with the post office and delivery services

- Home automation: Thermometers and heaters

- Industry 4.0, e.g., in the supply chain, see Section 6.2

- Heart rate monitors with GPS trackers

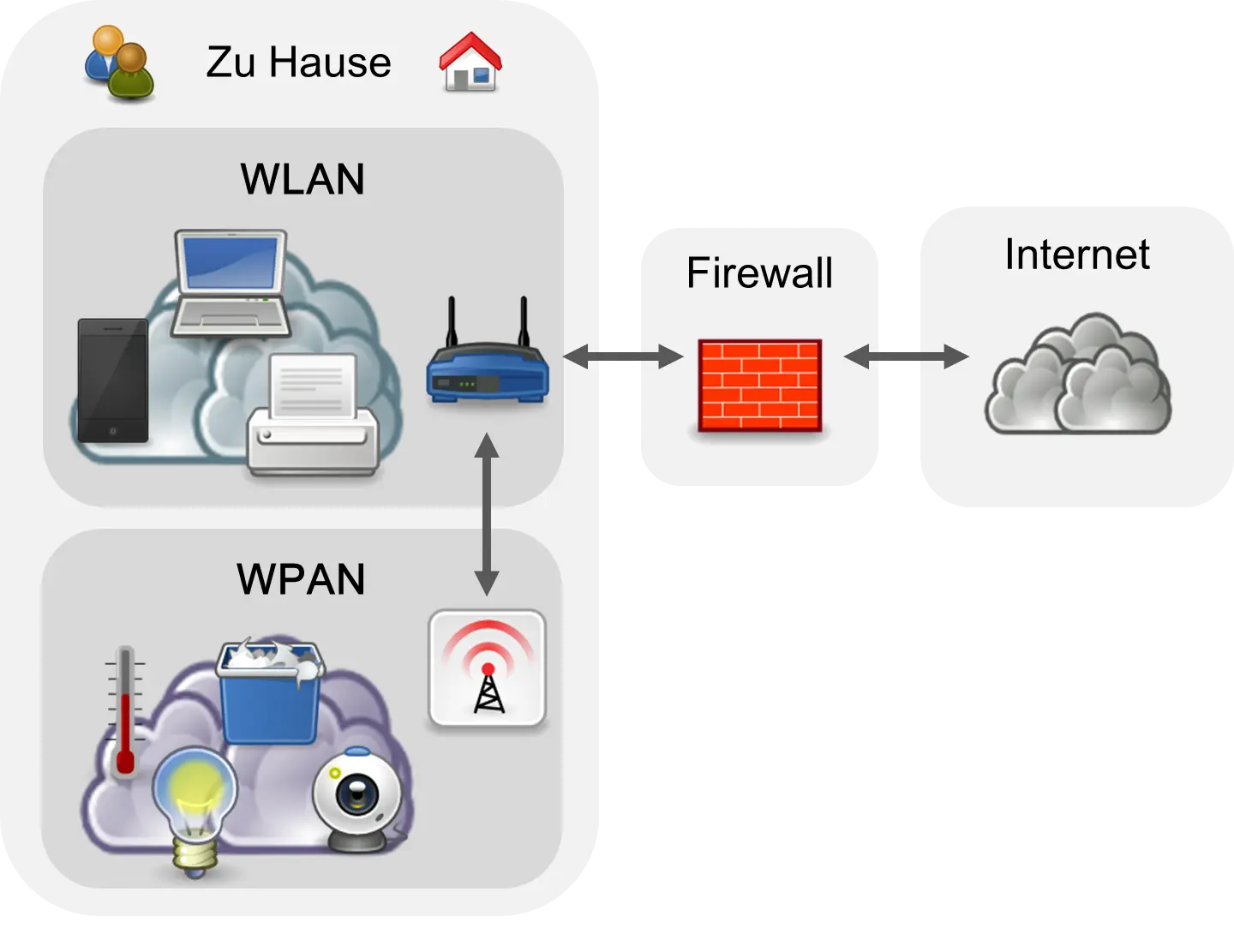

Currently, however, the production of WLAN components is still relatively expensive, so-called WPANs (“wireless personal area network”) were developed, whose network components are cheaper to manufacture. Here, however, the market is still in development and not as standardized as with WLANs, where the IEEE 802.11 standard exists. There are, among others, the following protocols [Gre15]:

- Bluetooth

- IrDa (“Infrared Data Association”) for infrared, e.g., for remote controls

- Z-Wave

- ZigBee

At home, you then have more than just one network, as shown in the following diagram.

You have a WLAN and one or even several WPANs. In the Internet of Things, everything is somehow connected to the Internet. The possibilities are endless and will significantly change the world. The new techniques are often designated with the prefix “Smart,” such as Smart Home, Smart Traffic, or Smart City.

Of course, there are also people who warn of the dangers, but—as can be seen from the figure—the WPAN is also protected from access via the Internet by the firewall. However, the future has yet to show how it is protected locally against attackers from the vicinity. But even here, the basic techniques already exist.

Identification with RFID

There are a lot of “things” in the real world that cannot truly communicate but only need to be identified. An example is a shoebox. For the shoe retailer, it makes sense to know if a shoe of size 46 is still in stock.

Therefore, the identification method RFID (“radio frequency identification”) was developed. RFID consists of a very small microchip that can store a number and the possibility of reading this number via radio waves. Often, the Electronic Product Code (EPC) is used as the number—an internationally used key and code system for a unique identification number. With RFID, the shoebox or even every shoe gets a very small chip glued on, and the shoeboxes are checked in and out at the entrance door of the warehouse.

In industry, RFID chips have been used by Walmart in the USA since 2005 on the pallets of suppliers [GB06]. Every pallet is uniquely identifiable via RFID, and thus Walmart was able to improve the logistical processes of supplying the markets. When a truck loaded with pallets arrives at a Walmart warehouse, every pallet is scanned with an RFID reader. The supermarket thus knows which products it has received and can update the database with the inventory. The company “knows what it has in stock.” Identification using the EPC could also be carried out with barcodes, but these must be “scanned” manually and visual contact is necessary. That is cumbersome. RFID uses radio, and the “scanning” can therefore take place automatically [Gre15]. RFID makes it possible to document processes better and obtain a better “overview”:

- Inventory can be determined automatically.

- For perishable goods, shelf life can be determined.

- Processes such as the supply chain or Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) can be improved. This reduces waste and losses.

- Processes could be “documented”: when the product was manufactured, when it was delivered, etc.

- In the case of defective goods, one can use the RFIDs to determine where in the production process the error occurred.

Since 2013, for example, Walt Disney World in Florida (USA) has been using RFID [JL14]. Every visitor receives a wristband containing an RFID chip. Visitors can book and/or reserve certain attractions via the Internet before arrival. For example, one can arrange a meeting with a Goofy character at a specific time. This avoids overcrowded events and queues in front of restaurants. The company, on the other hand, can use the data obtained in this way to further improve the park. Regarding data security, it should be said that only an artificial ID is stored in the wristbands. The booked attractions are determined using this ID in an encrypted database. According to Disney, this database contains no credit card data or other personal information. Personal data cannot be traced back via the wristband.

For security, it must be mentioned that there are now also RFID jammers and wallets that are scan-proof. RFID can therefore be bypassed if privacy is to be protected.

Machine-to-Machine Communication (M2M)

With RFID, a bridge can thus be built between the physical and the virtual world [Gre15]. This bridge between physics and information consists to a very large extent of machine-to-machine (M2M) communication. A thermometer sends its data to a WPAN receiving device, which sends the data further to a database on the Internet. This database is in turn used by a web portal with which a user can view the data. Important from a technical perspective is that these data transmissions work securely, reliably, and—in the case of confidential data—encrypted.

A lot of additional infrastructure is still needed here. A comparison with road traffic suggests itself: in addition to motorways, access roads, signs, gas stations, rest areas, motels, car workshops for repairs, etc., are required. It will be similar with the Internet of Things: devices, software, programming techniques, tools, etc. [Gre15]. A “nervous system” is emerging that can connect the devices in the world with each other. This connection must, of course, take place on a voluntary basis. It will also be possible to operate certain devices or services only within a private subnet or a “Virtual Private Network” (VPN).

Still in Development

At the time of writing (2015), the Internet of Things is on the S-curve in the status “in development” (see Section 5.6). There are still many things to learn and develop. Of course, there will also be setbacks and security gaps, at least for some products and for some users. Mistakes are made in every development.

Many critics have great fears here and fear the surveillance of people. If someone buys shoes and pays with a credit card, the shoe store could link the RFID of the shoes with the name of the buyer. When the customer enters the store again with these shoes, the shoe store can “recognize” the buyer. There are different opinions here: some would welcome this as a service, while others see themselves as being “monitored.” There will therefore be many more discussions about this in the future. However, this possibility already exists in car traffic without anyone getting upset about it. For every car has a clearly visible license plate.

The Improved Collective Intelligence

In the coming years, an Internet of Things will emerge that can be evaluated “semi-intelligently” with human help. The greatest progress will come from the combination of new techniques and data. New social networks and communities will emerge. Because more people can participate in the Internet, progress will be further accelerated.

Examples of the Internet of Things

The many devices in the Internet of Things will continuously generate data, which will be processed using Big Data and analyzed with Data Science. There are already rule-based systems today that trigger certain actions based on the data, such as ifttt2. A rule has the format “IF Sensor THEN Actuator.” There are adapters here for various software, devices, and social networks. Examples of rules and corresponding hardware available today:

- If the sun is not shining, turn on a light

- Read the headlines of a website and send them via email

- If the weather forecast predicts rain the next day, send an SMS

- Turn on the lights when you come home and it is already dark

These rules and services will certainly become more sophisticated and complex in the future. Later, more mature techniques with Artificial Intelligence will come into play, using decision trees or neural networks.

There are also many applications in the field of environmental protection. The “Hawaiian Legacy Reforestation Initiative”3 has set itself the goal of restoring the original ecosystem on Hawaii, which was destroyed by industrial use in the cultivation of sugar and pineapple. Here, volunteers can “donate” a tree. In total, more than 225,000 trees have already been planted [Gre15]. The administration and maintenance of these trees occur with modern technology, as every new tree gets an RFID chip so that it can be found again via its GPS coordinates. The care of the trees, possibly watering during droughts, etc., can be planned using the database.

In agriculture, many improvements can be achieved with moisture meters, thermometers, and pH meters, such as less and better-adapted fertilization and irrigation. With sensors, the management of free-ranging cattle is also easier [Dav14].

In logistics, such as with containers or parcel services, “tracking systems” have been used for some time. Here too, the economic savings are enormous. The environment is also protected if the delivery vehicles of the parcel services take fewer detours than before.

In so-called Smart Cities, traffic management systems could one day help avoid traffic jams and accidents and make it easier to find parking spaces. Self-driving cars will drive more energy-efficiently because they “oversteer” less than humans. They will accelerate and brake more purposefully than humans [Gre15].

The Internet of Things will therefore become both a telescope and a microscope. No industry will remain untouched by it. In connection with Big Data and Data Science, unimagined possibilities for progress [Gre15] and “collective intelligence” arise.

Application: Climate

With the Internet of Things, it will be possible to obtain much more data about the environment. This is where “environmental applications” will arise [HTT09]. These applications will manage and control various aspects of the environment, such as water quality. In research, better and more realistic models of the environment will emerge because more and better data are available. With inexpensive sensors, it will also be possible for the first time to explore previously unexplored parts of the large oceans with Big Data and AI. With the help of the combination of nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technology, computer models, image processing, and robotics, it will eventually be possible to research in the depths of these oceans with remote-controlled or autonomous robots.

Application: Health

Demographic changes in the world population—more old people, fewer young people—make an improvement in healthcare systems necessary. To maintain the same level of performance, productivity gains are required. When a new medication is introduced, it is important to react as quickly as possible if new side effects become known. This can be enabled, for example, by crowdsourcing [HTT09].

Medical research will benefit very strongly in the future from the abundance of health data and the analysis possibilities of Data Science. The number of misdiagnoses and medication errors can be reduced [HTT09].

Using scales, blood pressure monitors, and other sensors that send their data to websites for processing, automated warnings can be sent to people with certain diseases [HTT09].

A huge amount of news is generated in medical research. It is estimated that an epidemiologist would have to spend 21 hours every day reading new research reports just to stay up to date [HTT09]. A typical doctor should know about 10,000 diseases and syndromes, 3,000 medications, and 1,100 different testing procedures. This extensive knowledge is, of course, not manageable by individuals, and computer-aided knowledge management and diagnostic systems must be developed. One such diagnostic system is IBM’s Dr. Watson [BA14]. A doctor informs the system of the patient’s symptoms, such as a slightly elevated temperature, sweats, and a red rash, and the system suggests a series of possible diagnoses. The doctor then selects the diagnosis they consider appropriate.

Application: Financial System

Today’s money is issued by states, which use it, among other things, to pay the interest on their national debt. But it was not always like this. Money is a medium of exchange that facilitates trade. Before money was invented—in the era of hunter-gatherers—direct barter was necessary. A hunter who had one hare too many had to find a gatherer who wanted a hare and had something “tasty” as a countervalue. With money, it’s easier: the hunter exchanges the hare with someone else for money and then exchanges the money with the gatherer for berries. Money is therefore a very simple thing and naturally arose during trade. Even in the time of Ötzi, there were already small copper bars used for exchange [Rid10, Fer08].

Today, money is in state hands, and for various reasons, a mix of computer scientists, cryptologists, and market anarchists sought a digital currency that would not have the disadvantages of state currencies. Above all, the currency should not be controlled by a state.

In a digital currency, one would have a digital coin and could keep it digitally in an account app. When making a purchase, one would simply “transfer” the digital coin to other people. But with digital goods, copies are very easy! How can one prevent a digital coin from simply being copied and spent multiple times? A fraudster could try to use multiple copies of the coin as simultaneously as possible at different online retailers. They would only notice the fraud later, and then it would be too late.

One possible solution would be a central database in which all IDs of the digital coins are stored, along with which account a digital coin is currently on. Now, during a purchase, a retailer would have to query this database to see where the coin is currently located and whether the buyer truly owns it. That sounds well and good, but it has a major disadvantage: this database is central and therefore this system is fragile. What happens if this database fails or if a rogue hacks this database?

The developers of Bitcoin found an alternative: the so-called Blockchain. The blockchain is a peer-to-peer (P2P) network (see Section 2.3). The database is located on all participating computers. The blockchain can store which account a bitcoin is currently on. The technology behind it uses sophisticated encryption methods and is considered quite secure to this day [Ant14].

Bitcoin has many advantages, but at the present time also disadvantages. With Bitcoin, for example, people who have been excluded from the traditional credit economy, such as in many African countries, can also participate in international trade. However, at the moment, the handling of Bitcoin is not yet truly user-friendly, and it has happened that people have lost their money because they did not store the digital coins on their own computer but on a server. If such a server is then “hacked,” the bitcoins are gone. Of course, a new monetary system is also a magnet for all kinds of fraudsters and rogues.

The blockchain, on the other hand, can also be used for applications other than Bitcoin. Many more innovative applications will emerge here in the coming years [Swa15]. And the technology created here definitely threatens many parts of today’s financial system. Before computers and digitalization, the banking business was very profitable per customer. Back then, “banking” was labor- and legal-intensive. Then computers came, and calculations were automated. After that came the Internet, and customer relationships could be moved to the Internet. Today, there are “unbundled” banks that no longer have real branches, but only a website and a few service employees for the telephone hotline. It is very difficult for a bank today to still make money with its former core business. Critics even speak of an end of banks [Mil14]. The financial market will therefore change significantly in the coming years.

The Distant Future: The Singularity

Section 9.1 explained why the speed of progress increases due to the “Law of Accelerating Returns.” We have also seen curve diagrams for exponential growth and know that the curve at the end rises almost vertically. Will research be the same? Will as much research be done in one year as formerly in 100 years? Several futurists have given thought to these questions. The central point for these considerations is whether computers truly become as intelligent as humans and what they then do with their intelligence [Kur06, Sha15].

The central hypothesis is: if “intelligent machines” should ever exist that are just as intelligent as humans, then these machines could improve themselves and make themselves even “more intelligent.” These “more intelligent” machines could in turn do the same, and thus, after several steps, “hyper-intelligent” machines would emerge. This moment is called the “Singularity”. A singularity is a single important moment in a system. A moment when something happens that has a very large impact. In physics, for example, the Big Bang is a singularity, or a black hole.

Many critics of AI fear that this “recursive self-improvement” could become the end of humanity [Bos14]. They assume an “explosive” and very rapid development of a super AI that is much more intelligent than humans. This super AI could then seize world dominance because, through networking, all systems are interconnected, and it would be no problem for the super AI to bypass security mechanisms.

But there are a few things wrong with this scenario, and there are many scientific counterarguments. The biggest error is that we imagine in our current world what the consequences of such a super AI would be. What if people at the time of Jesus Christ had been told about tanks? They would have feared their demise because they could not have defended themselves against a tank. From the perspective of the time, a tank is unassailable and invincible. Today’s Italians, however, would not be truly impressed by a single tank. It is similar when we imagine the consequences of a super AI today. For by the time of the singularity, the world must have already changed beyond imagination. Before you can produce an AI that is as intelligent as a human, you must have produced AIs that are, for example, as intelligent as dogs or cats. And this would already change the world indescribably.

Another error is that inventions do not arise abruptly or explosively. They are the result of combinatorial innovation and collective intelligence. The super AI would have to be more intelligent than the 6 billion people living on earth.

Furthermore, intelligence in humans arises from an “intelligent” combination of Systems 1 and 2 (see Section 3.2). Human thinking is a mixture of time-saving heuristics from System 1 and careful trial of all possibilities with System 2. Both systems can be “simulated” by computer systems: System 1 by neural networks and System 2 by search algorithms, mathematical differential equations, or by simulations with agent-based modeling. A super AI cannot solve differential equations faster than a traditional supercomputer, however. An NP-complete problem is also NP-complete for a super AI and thus requires a long calculation time. Many optimization tasks are NP-complete, and today’s computer chips are already improved with mathematical optimization by computer algorithms. If this already happens mathematically optimally today, the super AI can improve nothing more here. A super AI would also be dependent on traditional computers, for they can do “number crunching” faster.

Moreover, economic aspects are completely missing in these critics’ views: computers need energy. Today’s supercomputers require the energy of entire power plants. This super AI would be very expensive initially and thus only operable by large states.

Nowadays, the trend is toward distributed systems. These systems consist, for example, of thousands of computers that together represent the system. Today, computing power is distributed across entire countries and populations. A super AI would certainly be a distributed system with a rather low computing power compared to the rest of the world.

Also, not all systems are interconnected. Many networked systems are in demilitarized zones secured by firewalls. Encryption methods and passwords are just as hard to “hack” for the super AI as for today’s computers and humans. So one cannot simply conquer the entire world via the network.

And as mentioned in Chapter 8 about AI, it has not yet been scientifically proven that a human-like AI will ever exist. Today’s AI only simulates intelligence. Whether creative and self-aware computers will truly exist one day is not yet certain today.

Since today’s AI based on silicon-based computers could not show the desired success, many futurists have switched to the imitation of human brains. They draft a—today still completely fictitious—theory that the human brain can simply be read out like a data storage device and rebuilt mechanically or via biotechnology. And thus one would then have an AI that is as intelligent as a human [Kur06]. Here, too, it is not yet scientifically clear that this is even possible. The brain is much more complexly structured than a computer. It is a complex network with different parts that react with each other chemically and electrically. Whether this can be simulated in computers is still open [Sha15].

That these goals are still far off can be clearly seen from the OpenWorm project4. Here, researchers are trying to recreate the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans in software. Caenorhabditis elegans grows up to one millimeter in size, and the male worm has 1,031 somatic cell nuclei and a brain with 304 nerve cells. Using a computer model, researchers have tried to better understand the organism of the worm. A first finding is that, despite the simple structure, it is very difficult to understand and recreate the complex interactions of the individual parts. Many questions are still open. The project is a beautiful example of the fact that progress can also be achieved in biology with the simulation of complex systems. On the other hand, a human has an estimated 100 billion nerve cells with 60 trillion synapses (connections). We are therefore still at least 10–20 years away from a simulation of the human brain.

In recent years, there have been reports in the media in which researchers reported the successful simulation of a brain. Here, however, one must take into account that a brain can be modeled and simulated with a different degree of abstraction. These simulated “brains” are highly simplified models. The complex chemical brain was reduced to a complicated neural network.

Interested readers are referred to the book by Murray Shanahan [Sha15] or to the “original” by Raymond Kurzweil [Kur06].