Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

Economies as Complex Systems

What is Economics?

Economics is the science of the economy. It is one of the disciplines with the greatest influence on people’s lives because the ideas of economists influence politics and, via the media, public opinion. Economists are consulted on all economic events: the current economic situation, the investment climate, or the mood on the stock market. Bad economic ideas have already cost many people their lives, such as the nationalization of all means of production in Soviet socialism.

What is economics as a field of study?

To define economics, the concept of an economic good must first be clarified. “Goods” describe commodities and services. A person’s working time is also a good. Sometimes a good is also called a resource. These goods are usually not available in arbitrary and sufficient quantities. In economics, they are then said to be “scarce.” However, “scarce” is used differently in everyday life. In colloquial language, something is scarce when there is very little of it left. In economics, “scarce” means that it is not available in unlimited quantities. For example, oxygen-rich air on the North Sea coast is not scarce, while plots of land near the beach are scarce—meaning they are only available in limited numbers. Most goods are scarce. A good can be used in different ways: a piece of wood can be turned into a guitar, a piece of furniture, or a pencil. One could also burn the piece of wood and convert it into heat. The violin maker requires different wood than the furniture manufacturer. Who decides which trees should be planted when land is scarce? Wood for violins or for furniture? Who decides how a specific good is utilized?

Now we are ready for the definition:

Economics is the science of the efficient distribution of scarce goods with different possible uses.

Since human society is a complex system, and the economy serves to satisfy human needs, the economy is also a complex system. Economics is therefore also a science of a complex system.

Economics has a rather dubious reputation. This is largely due to the fact that findings are constantly taken out of context and misused for political purposes. One example is the “invisible hand” by Adam Smith (1723–1790). Adam Smith used this metaphor to describe emergent behavior because there was no better word for it at the time. People act locally and only for themselves and their family and friends, but seen globally, much is steered “bottom-up.” However, as soon as any economic crisis emerges, Adam Smith and, by extension, the entire market economy are criticized:

Adam Smith supposedly said the “invisible hand” would regulate everything at all times. And since the financial crisis exists, the “invisible hand” cannot exist; therefore, the market economy is useless and Karl Marx was right after all.

But Adam Smith mentions this “invisible hand” only once in each of his two major works, “The Wealth of Nations” and “The Theory of Moral Sentiments.” The “invisible hand” was never the central point of his work. Nor did he say it would regulate everything, as Adam Smith belonged to the “constrained vision” in which humans, and thus society, have many flaws, as mentioned in section 3.4.

The statements of economists are heavily distorted in political discussions. Something similar happened to John Maynard Keynes [CK14], who would likely be just as dissatisfied with today’s Keynesianism as Karl Marx would be with Marxism [Des04].

Important: Economists are often misrepresented and misinterpreted.

Criticism of Traditional Economics

Because economics is so important for politics, theories that are politically desired but scientifically untenable often prevail. This hampers further development. No other science cites such old scientists so frequently: Adam Smith lived from 1723 to 1790, Karl Marx from 1818 to 1883, and John Maynard Keynes from 1883 to 1946. Economic researchers themselves do not do this, of course, but the general public seems to have “stopped” at a basic level of economic knowledge from that era.

How did this happen?

Historical Development

The book “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,” published by Adam Smith in 1776, is considered the first modern examination of economics [Bei07]. The book addresses questions such as:

- How is wealth created?

- How is wealth distributed among the population?

- What are the consequences of the division of labor?

- What is productivity?

- Should the state intervene in the economy?

Adam Smith still saw himself as a philosopher, and therefore the book is not mathematical. At that time, mathematics was still in its infancy. During Smith’s lifetime, physics had made great strides thanks to Isaac Newton (1642–1726). Newton saw the world through “mechanical glasses,” and for him, the world was one giant physical machine. This perspective also influenced philosophy and other sciences [Gil13].

During the “Classical Period” from 1680 to 1830, the relationship between supply, demand, and price was discovered (see Section 5.3) [Bei07]. However, the question of how to name or predict the “correct” price remained open. At that time, it was still believed that the price was objective rather than subjective. In physics (in Newtonian mechanics), one can use the right formula to make predictions about the future. It is possible to calculate how planets rotate around the sun or at what position a pendulum will be in 2 seconds. Economists at the time thought they could achieve this same predictability by performing a “mathematization” of Smith’s work. This was not immediately possible given the state of mathematics back then. Only after calculus was further developed by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), Leonhard Euler (1707–1783), William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865), and Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) and successfully used for physical and astronomical problems could economics become more “mathematical” during the Marginalist Period from approximately 1830 to 1930. This required the work of three economists: Léon Walras, William Stanley Jevons, and Vilfredo Pareto [Bei07].

However, mechanics and economics differ greatly. To transfer mathematics to economic problems, several simplifying assumptions had to be made. Léon Walras, for example, took the concept of “equilibrium” from physics. Since then, many economists have focused on these equilibria. Traditional economics views the economy through the eyes of physics. Imagine a rubber ball moving inside a very large bowl. Eventually, it comes to a stop. Equilibrium occurs. Now someone external must nudge the bowl for the ball to move again. The economy thus moves from equilibrium to equilibrium. States outside of equilibrium are not analyzed. Walras made a trade-off here between predictability and loss of reality. His model can no longer be applied to the actual economy. It is a simplification. For that time, it was still a major step. Walras applied mathematics to a new field. But his willingness to make simplifying assumptions so that the problem remained mathematically manageable has been maintained in economics to this day [Bei07].

William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) wanted to make human behavior as predictable as gravity. He was familiar with the works of Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell on gravity, magnetism, and electricity as “fields of force.” He assumed that price in economics corresponds to energy in mechanics.

Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923) was the first to research the foundations of game theory (see Section 3.3). Pareto recognized that most people voluntarily only engage in win-win actions. And if everyone wins, general prosperity increases. He thus laid the foundation for the assumption that humans always act “optimally.”

The 20th century saw the rise of the Neo-Classical School, in which equilibrium economics was expanded and new variations of simplifying assumptions were tested. In the 1980s, Paul Romer in particular further developed Growth Theory, though these theories also rely on “physical mathematics” and differential equations.

Traditional Economics is Based on Physics

Classical physics is deterministic: atoms always behave according to laws of nature. If the state of a deterministic physical system is known, predictions about the future can be made. An atom has no free will, cannot learn from the past, and cannot change its behavior. To apply mathematics developed for physics to economic problems, economists have made many simplifying assumptions over time, such as the following [Rid10, Gil13, Kah12, Bei07, Tha15]:

- Complete Information: Humans know all products, all dealers, and all prices.

- Perfect Rationality: Humans automatically do what is optimal—i.e., they always make the best move in chess. This model was called “homo oeconomicus.”

- Perfect Competition: No monopolies, complete transparency.

- Perfect Markets with omniscient participants.

- No transaction costs, such as taxes and fees.

- The assumption that products are sold only based on their price and not based on their appearance or brand name.

- The assumption that a product costs the same everywhere. In reality, the same product often costs different amounts in different supermarkets.

- All firms work as efficiently as possible and have no “frictional losses.”

- Time jumps from equilibrium to equilibrium.

These assumptions, however, separate economic models from reality. We know from behavioral economics that humans do not possess these capabilities (see Section 3.2). Economics has created mechanical models of a complex and dynamic system driven by humans.

Important: Economists have reduced a complex system to a complicated system.

This is by no means intended to diminish the achievements of economic science. Economists have performed important work that holds a significant place in human history. But from today’s perspective of complex systems, traditional equilibrium economics is not accurate.

Complex Economics

The Economy as a Network

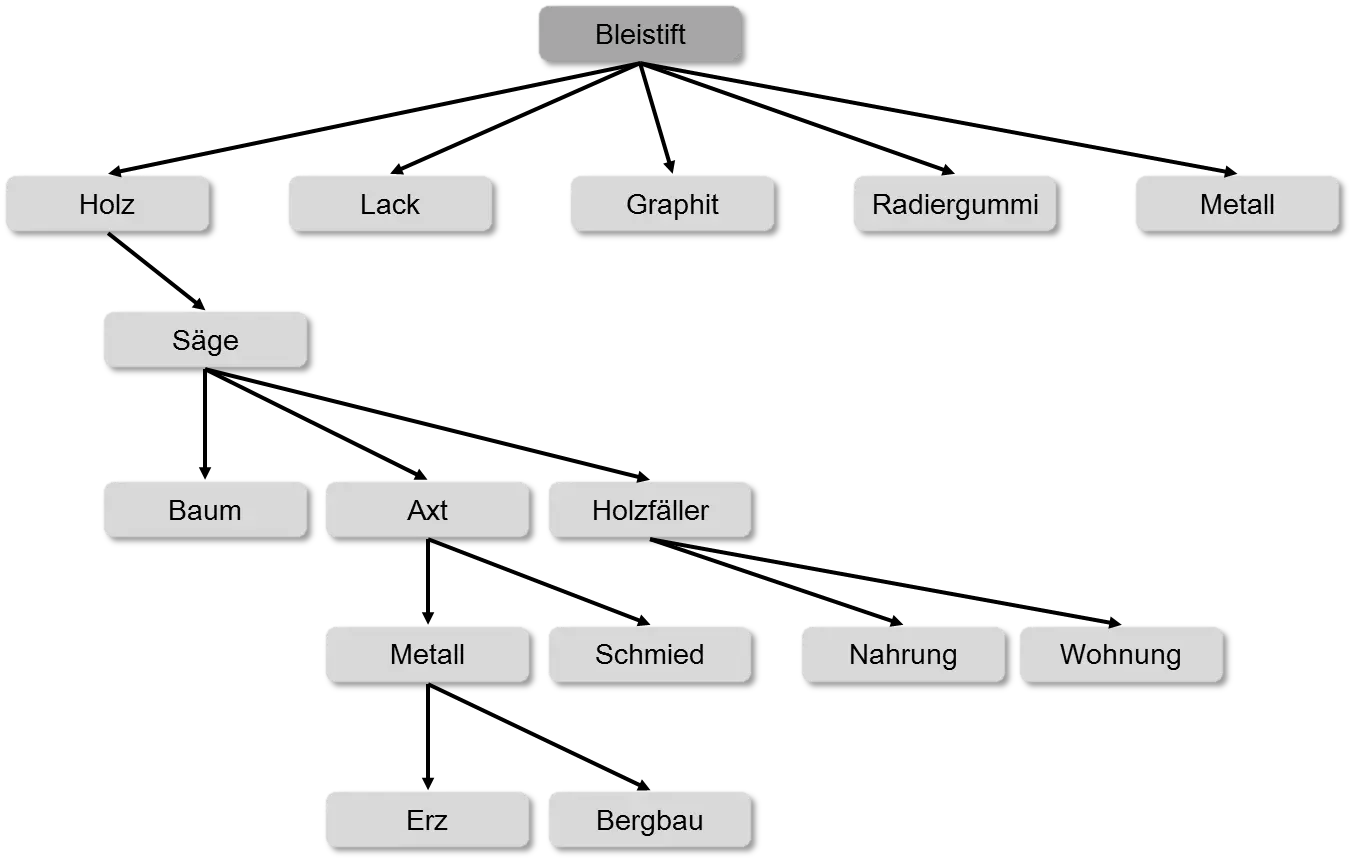

The story “I, Pencil” by Leonard E. Read provides a beautiful illustration of the world’s complexity [Rea58]. In this story, a pencil describes its “family tree”—its origin, what materials it is made of, and who produced those materials. Furthermore, it describes what was necessary in turn to produce those materials. The astonishing message of this book is:

No single person can make a pencil alone.

Because they require the products or services of other people to do so. The pencil itself is made of wood, lacquer, graphite, and has an eraser at the top end enclosed by metal. The wood itself is a specific species of tree that must be neither too hard nor too soft. A pencil must be easy to sharpen; if the wood is too hard, that won’t work. The wood comes from a tree felled with an axe or a chainsaw by a logger. Perhaps the wood was transported by truck or rail. The following diagram shows a very small excerpt from the pencil’s “family tree.”

It is the beginning of a truly complex network and a complex system. If you think about it further, it borders on a miracle that it works. Many different individual parts and subsystems cooperate asynchronously to ultimately produce a pencil. And all this without central control, without a total plan. This is what Adam Smith called the “invisible hand” (but only once per book!). Today, one could call it “collective intelligence” or a “collective brain.” The knowledge to produce a pencil is distributed widely across society. One of the first economists to examine this more closely was Friedrich August von Hayek (1899–1992) [Hay48]. Hayek was an economist belonging to the Austrian School of economics. This school differs from traditional economics because it understands economics as the actions of individuals. The economy is the result of human actions. The economy is viewed “bottom-up” rather than “top-down.” Therefore, mathematical models were rejected. Consequently, Hayek did not view the economy through the lens of (physical) mathematics and equilibria. His view was not “distorted” by mathematical models. According to Hayek, the economy is a decentralized system similar to agent-based modeling. In his 1948 essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” there is a quote that is remarkable from today’s perspective [Hay48]:

“We must look at the price system as such a mechanism for communicating information if we want to understand its real function—a function which, of course, it fulfils less perfectly as prices grow more rigid.”

This was in 1948: Communication and Information! These were completely unknown concepts at the time. In the same year, Claude Shannon published his article “Mathematical Theory of Communication,” which is considered the cornerstone of information theory today. Friedrich Hayek did not remain unknown either; he received the “Nobel Prize” in Economics in 1974.

Supply, Demand, and Price

Prices communicate information. What information do they contain? How do they do it? And if prices are manipulated—for example, through laws, price floors, price ceilings, etc.—do they lose this information?

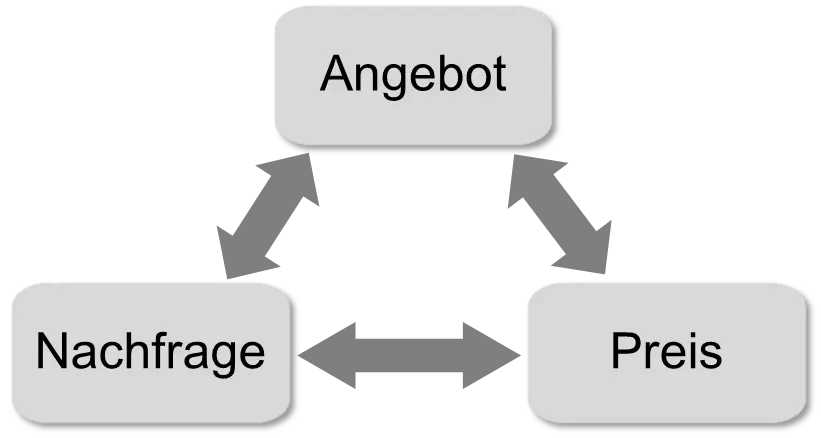

Goods are traded in markets: people can offer goods, and others can buy them. A distinction is made between supply (what people want to sell) and demand (what people want to buy). There is a connection, a dependency, between supply, demand, and prices. They are not independent variables but influence each other. This relationship between supply, demand, and price was discovered earlier in the “Classical Period” of economics from 1680–1830 [Bei07]. It is also covered in mainstream textbooks, such as Paul Krugman and Robin Wells [KW05]. The following diagram outlines these mutual interactions:

Let’s assume a test person sees an item in the supermarket that they have used for years and want to continue using because it is so good. The item is on sale for half the price. How many does the test person buy? Naturally more than usual, because they build up a supply, provided it is not a perishable good. The lower price leads to more being bought. Conversely, purchases are reduced when items become more expensive than before. The test person will try to get the item cheaper elsewhere or switch to another product. The higher price leads to less being bought.

Important: Supply, demand, and prices influence each other and cannot be viewed in isolation.

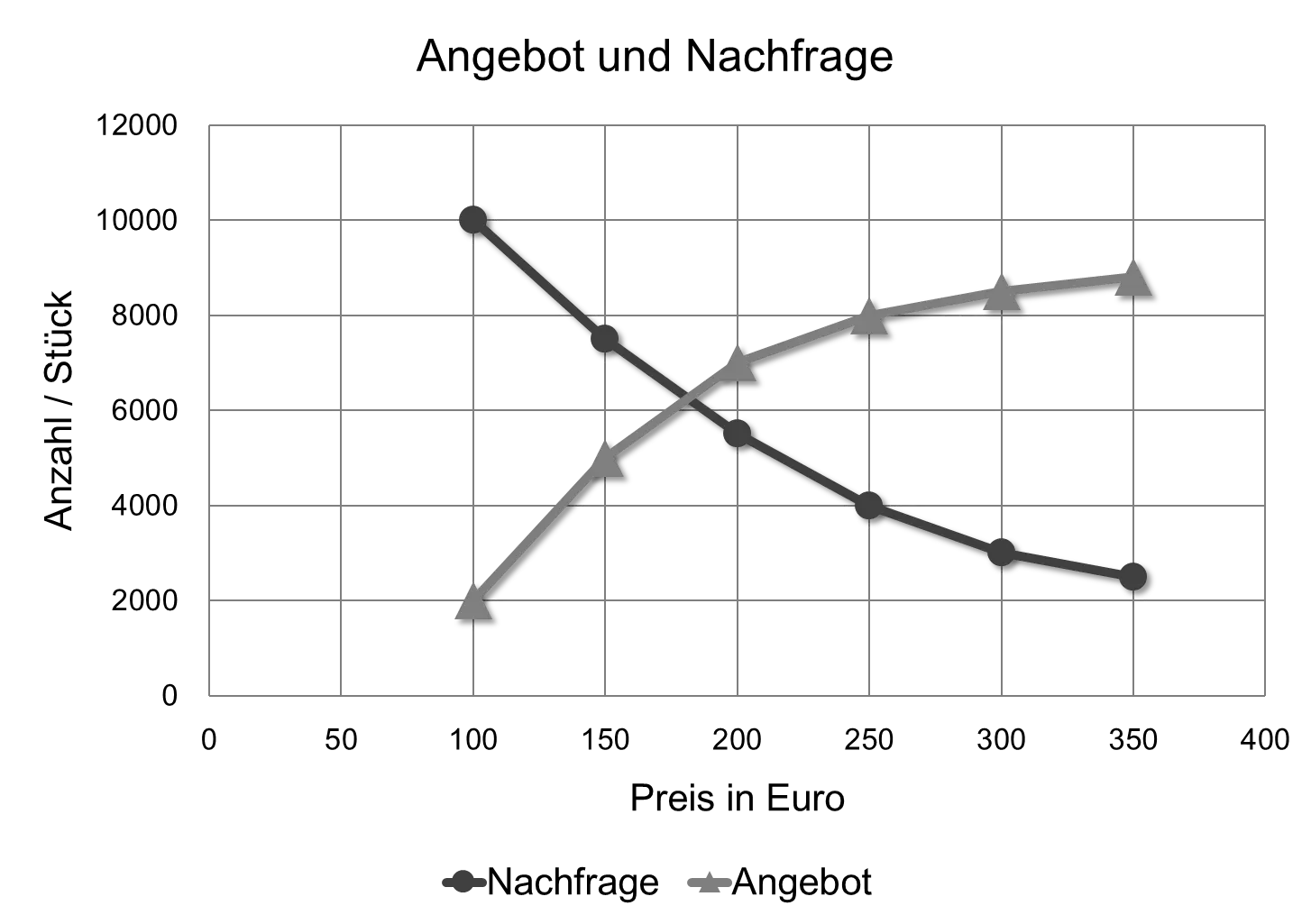

Economists usually explain this relationship in a supply-and-demand diagram:

Two curves are drawn here: supply and demand. On the horizontal x-axis is the price in Euros; on the vertical y-axis is the quantity.

The demand curve slopes downward because the more expensive the product becomes, the fewer people want to pay the high price. The supply curve slopes upward because sellers want to sell at the highest possible price. There is a dualism here—two opposing forces that must agree in the middle: sellers generally want to sell something as expensively as possible, while buyers want to buy something as cheaply as possible. Both must agree on a price. It is an “optimization process,” a “price discovery process,” a kind of auction.

With every purchase, a decision-making process (“Do I buy this or not?”) occurs within a person. Millions of times every second on Earth. These are intelligent decisions that take place in a distributed and decentralized manner.

Important: With every purchase or sale, an “optimization” of the economy occurs.

So far, we have only viewed the relationship as a buyer. Let’s put ourselves in the position of a flower seller. We have 1,000 roses and must sell them soon before they wither. We want to work for 8 hours. We set the price at 1 Euro per rose, and after four hours, we notice we have already sold 900 roses. We sold them too cheaply! Experienced sellers know this and adjust prices automatically. Large online retailers, for example, measure the sales velocity for every product in units per hour. This allows them to calculate when they need to restock their warehouse. If something sells too well, the price is increased; if it sells poorly, it is lowered.

The temporal change of a price therefore has a signaling effect and indicates whether supply or demand has risen or fallen. If a good cost 90 Euros yesterday and 100 Euros today, that could be due to increased demand or a tighter supply. But the price change sends out the information that something has changed.

Now let’s put ourselves in the position of an entrepreneur. Let’s assume the entrepreneur wants to earn as much as possible. However, they do not yet know which product they should manufacture for this purpose. Is it better to produce cleaning supplies or vacuum cleaners? We will ignore the production factor of “knowledge” for a moment. Let’s assume an entrepreneur could learn very quickly how to make these things. They will then choose the products where they can make the most profit—i.e., where the largest “margin” exists between the selling price and the manufacturing cost.

To do this, they need information about past market developments and a sense of what people will buy in the future. An entrepreneur must guess the future. They perform an experiment by manufacturing a product. They take on the “entrepreneurial risk.” Employees take on only a small part of this risk; they receive a monthly salary. A company, however, may have to have a product developed over years and “advance” the investments. Now the entrepreneur compares prices and sees that the prices for cleaning supplies have risen very sharply. This signals that money can be made with cleaning supplies. They start producing cleaning supplies. As a result, there will be more cleaning supplies again next year, and prices will drop again. Contrary to widespread belief, one cannot simply “make” or set prices. Prices emerge as an emergent property of a complex system.

What happens to this information when prices are manipulated through political intervention in markets?

- Price ceilings

- Price floors

- Guaranteed purchase prices for green electricity

- Rent caps

- Minimum wages

- Fixed book pricing

According to Paul Krugman and Robin Wells, such interventions have “unpleasant side effects” [KW05]. They even title the chapter “The Market Strikes Back”. Underlying this is the insight that in complex systems, an action always has unintended side effects. An intervention in the price system thus produces not only the desired effect but also side effects that are sometimes difficult to foresee but often follow quite logically. If, for example, a state were to set a uniform wage (a maximum and minimum price) so that everyone earns the same, it would not be worthwhile to invest much effort in education. Whether one can do math or not, one would earn the same later.

It is, however, somewhat surprising that politics in Germany is increasingly reintroducing price manipulations, such as with the minimum wage or the rent control brake (Mietpreisbremse). It was a key feature of the “Economic Miracle” (Wirtschaftswunder) that Ludwig Erhard abolished the price controls introduced by the Allies [Erh57].

Important: With the help of signals sent by price changes, markets allow for a degree of self-regulation. For this to happen, however, information must still be contained within the prices.

The Economy as an Information System

Information Theory

Prices communicate information, but what exactly is information? The term “information” was precisely defined only in 1948 by Claude Shannon in his article “The Mathematical Theory of Communication” [Gle11]. At that time, however, it was mainly about transmitting messages via radio.

A technician who wants to transmit or store a message needs to know the length of the message or how much space it requires on a data carrier at minimum. According to the technical definition, the information of a message is therefore the maximum compressed message itself. The length of the message is given in bits. A bit is the smallest distinguishable unit of information, usually represented as 0 and 1. A fair coin toss, where each side (heads or tails) is equally probable, also has information of 1 bit.

Information can be interpreted as the reduction of uncertainty regarding the state of the world. Before the coin toss, one is uncertain about the result. There is no information about how the coin toss might end. Both possibilities are equally likely. The coin toss itself reduces this uncertainty. It is similar to a weather report when planning a trip. Before the trip, one is uncertain about the weather at the destination. Will it rain or snow? The information contained in the weather report reduces the uncertainty. Here one must distinguish between absolute and relative information. If you read the weather report twice, the second reading provides no new information. Relatively speaking, the report contains no more new information. Absolutely speaking, the same storage space is necessary to save the report, so it contains the same absolute information.

Uncertainty regarding the state of a system is referred to in physics and information theory as entropy. The system must be in exactly one of many possible states. However, one doesn’t know exactly which one and can only provide probabilities. Let’s imagine the “physical” system with the three circles from Section 2.3 again. We know from the source code where the circles are located. We have absolute knowledge. Entropy is minimal. Suppose a computer error had changed all data randomly. We wouldn’t know where the circles are, what size, color, position, and “velocity” they have. We then have the greatest uncertainty about the system. The circles could be anywhere, and we would know nothing about the state of the system. Entropy is then maximal.

To reduce entropy in a physical system, work or energy must be put in. To reduce entropy in an information system, information must be added.

Information in the Economy

The entropy of an entrepreneur… oh, a tongue twister… second try… so, the uncertainty of an entrepreneur about the further course of the economy needs to be reduced. The entrepreneur wants to manufacture and sell products. But which ones? And what should they look like? Their entropy or uncertainty is high. They need information to lower their entropy, to lower their ignorance. Just as a physicist takes measurements, an entrepreneur performs market analyses or tries to generate new information from existing data with the help of Data Science. Everything serves to reduce ignorance. It is similar for a stock trader. A stock trader does not know how prices will develop, which stocks to buy, and which to sell. They are uncertain in their assessment of the future. They do not know how a specific company will develop or how the economy will develop in general. They need information.

George Gilder worked as a stock trader in the 1970s, and at that time, it was important to collect as much information as possible about companies and find out which companies were in good standing and likely had a good future [Gil13]. He writes that as a trader, he had to constantly look for surprises, for new information. This allowed him to reduce his uncertainty; he had more knowledge. Trading stocks was heavily knowledge-driven.

And he also writes that this no longer works today because the information is no longer there. In the 1970s, for example, indices were developed to diversify risk. An index is a so-called weighted sum of several values. An example of an index is the average. The average is the sum divided by the count. Let’s take the set of three numbers {1, 3, 8} as an example. The average is (1 + 3 + 8) / 3 = 4. The average is a weighted sum where the weight is always the same—in this example, 1/3: 1/3 * 1 + 1/3 * 3 + 1/3 * 8 = 4. One could now give the middle element more weight (1/2) and the other two elements less weight (1/4): 1/4 * 1 + 1/2 * 3 + 1/4 * 8 = 15/4 = 3.75. Such a weighted sum of individual prices, however, destroys the information contained in the individual prices. it “blurs” them.

According to Gilder, indices lead to information dumps and hide important information [Gil13]. If you want to make money on the stock market, you have to be better than the indices. This requires knowledge, information, surprise—the deviation from the norm. In stock trading, all known information is already priced in. Only news counts and triggers changes. The news must be evaluated by the trader, and they must act accordingly—i.e., buy, hold, or sell. Originally, indices were developed as a means of reducing risk. Individual indices are robust in the sense of Nassim Taleb (see Section 2.7). But the overall system is then not necessarily robust anymore; it may become fragile. Individual indices cannot crash, but the overall system becomes more brittle [Tal12].

What was once knowledge-driven stock trading has become a game of chance—casino capitalism. According to Gilder, there have been many more regulations in the American financial system in recent years aimed at avoiding risks and crashes, but in reality, they make information very hard to find [Gil13].

Important: Today’s stock markets suffer from information loss.

Today’s financial system will be discussed later in Section 11.3.

Markets

Supply and Demand

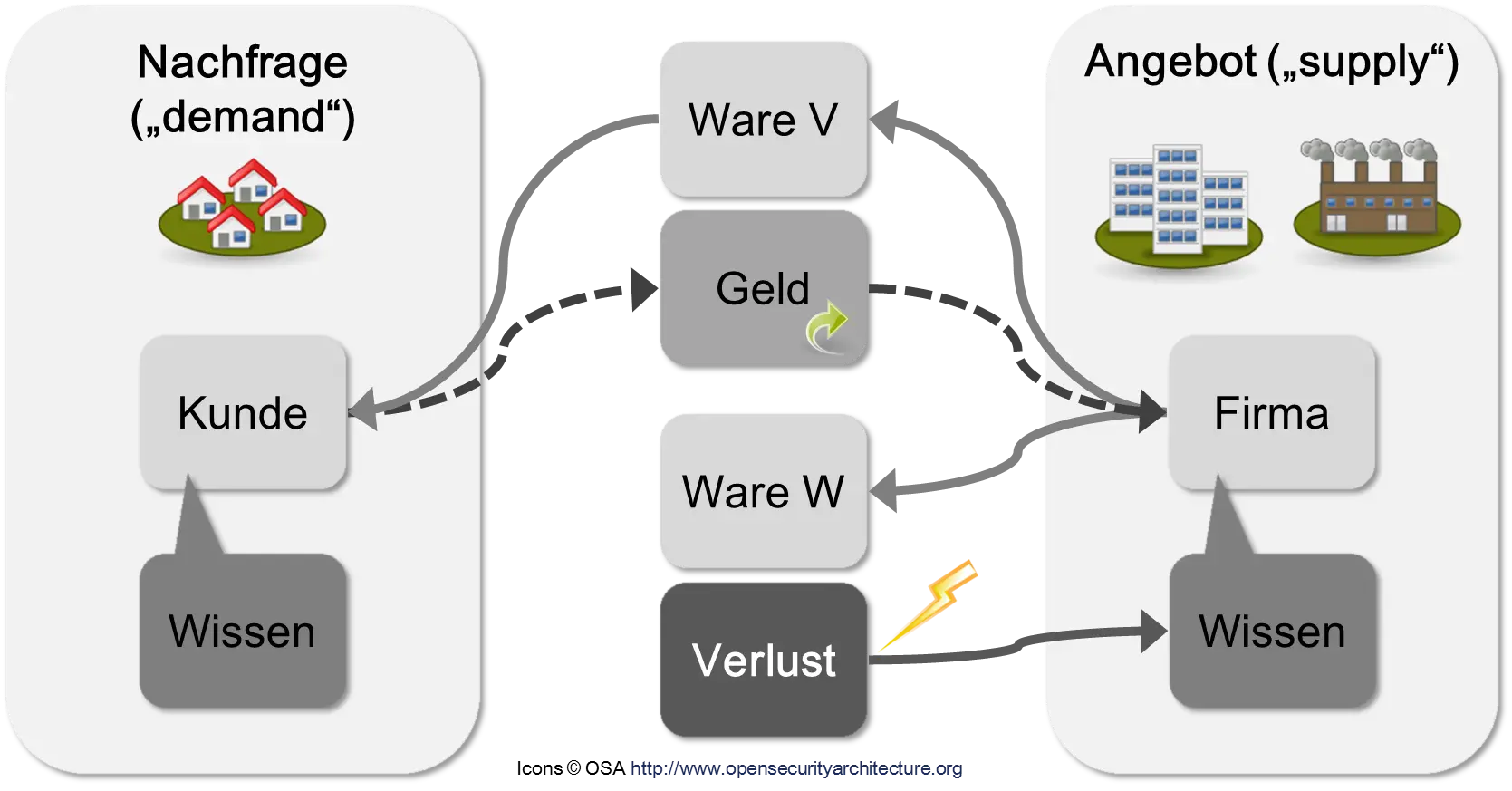

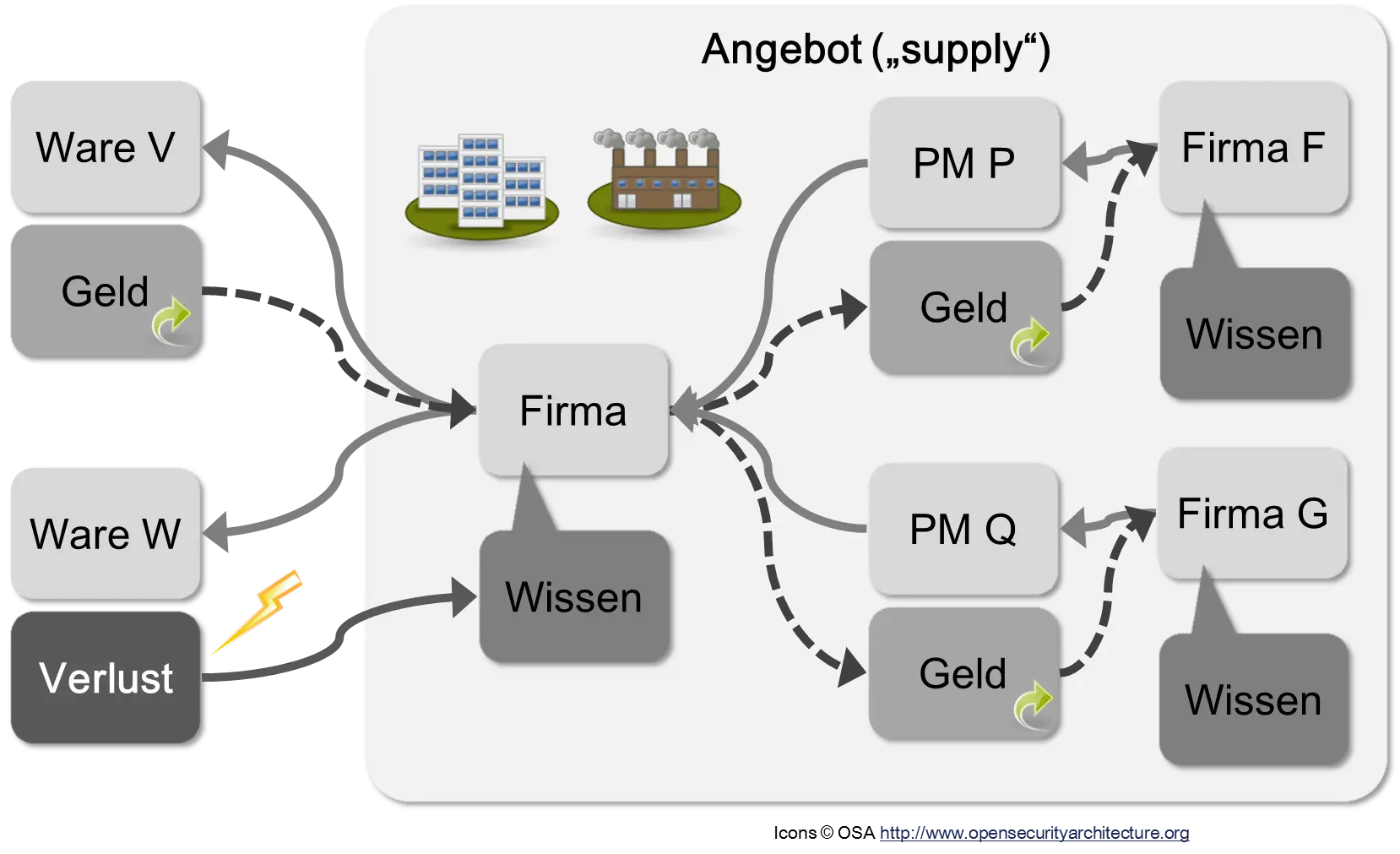

The task of an economy is to provide people with goods and services. The following figure shows a simplified overview.

The economy is divided into two sides: demand and supply. Demand refers to all customers and buyers of goods and services. Supply includes all companies. In the figure, a company offers two different goods, V and W. Good V is bought by a customer who pays for it with money. The customer and the company thus exchange money for good V. The company gains the information that good V is useful. It also knows now that good W is not needed. The company’s knowledge has increased. A company’s knowledge can be illustrated in a kind of learning curve. For the company, launching the two goods was an experiment, a test. The top product passed the test; the bottom one did not. The company thus receives both a financial reward and valuable information. For George Gilder, it is an essential element of the market economy that these two types of information—the financial reward and the knowledge of how to produce the product—remain together within an organization. The one who earns the money should also be the one who reinvests it. This makes a repeat success more likely [Gil13].

In all economic discussions, it is important to always consider both sides: supply and demand. How does a regulation or a law affect demand, and what impacts does it have on the supply side? Supply and demand have a dual relationship to each other. They can be well-imagined as the Yin and Yang symbol of Chinese philosophy.

There is a chicken-and-egg problem here: which came first, the chicken or the egg? Does supply create demand, or does demand create supply? On which side should regulations and interventions in economic policy focus? There are also different schools of thought in economics:

- Supply-side policy sees supply as the more important side. Political interventions should support companies and expand supply or make it cheaper.

- Demand-side policy, whose most famous representative was John Maynard Keynes, sees demand as the key element. Interventions here are intended to increase demand.

On which side is more knowledge present? With supply or with demand?

With new technical possibilities, socialists came up with the idea that with the internet and semi-automated factories, a (semi-) socialist planned economy could now be implemented. One would only need to ask customers via an “app” which goods they would like, and then one could produce them accordingly in a “socialist” manner. Demand has been determined, and a grand plan is set up according to which the supply side is to be organized. In a planned economy, the supply side has no “free will” but must obey the orders of the plan.

Information about customer desires would indeed be relatively easy to determine—for example, with a website and “apps” for mobile phones. We are ignoring the objection here that this would require a “transparent citizen” without privacy, where the state would know the entire consumption behavior of the person. So, the problems of the demand side are solved. But what about the supply side? Does it just continue as before? How then do new products arise? In reality, the supply side is much more complicated than the demand side. It is a very complex network, as we know from the story “I, Pencil.” The following figure now also shows two “supplier companies”:

The company uses the means of production (MP) P and Q to create goods V and W. A “means of production” is understood as a good used for the manufacture of other goods. A robot in a factory is a means of production. An oven at a baker’s is, too. The classification of a means of production also depends on its use: a laptop for a journalist who uses it to write texts that he sells is a means of production. The laptop is no longer one if the journalist uses it to play computer games. An open question for socialist societies was who decides when something is a means of production and belongs to the state, or is private property.

Now company F has used means of production P to produce V. Who decides how long P is used and when it is replaced by a newer means of production? If sold at the right time, money can perhaps still be made with it. If it breaks, it is repaired or replaced. These decisions are made decentrally in an economy where the means of production are privately owned—every company decides for itself. Whether the company can produce at all is decided by the customers who buy the product.

The complexity of the supply side of the economy is hidden from many proponents of a “planned” economy. Even if, in the age of the internet, the demand of end consumers can be easily determined, who determines which means of production P and Q are manufactured? What means should in turn be expended for that?

In many variants of socialism, these means of production are to be nationalized and a central planned economy introduced. To create this plan, however, one must possess the knowledge of the supply side. The knowledge distributed across individual companies in a market economy must therefore be centralized. But the “transfer” of knowledge to a planning ministry is anything but simple. Knowledge can only be “learned” by people, not simply “transferred.” This “knowledge problem” of the central planned economy comes from the previously mentioned work of Hayek [Hay48]. Centralizing the economy would place a great deal of economic power in the hands of a few planning officials. It is the advantage of a market economy that both knowledge and power are decentralized—the more distributed, the better [Gil13].

A further question is who determines the price of the means of production if they are all owned by the state? The state would then be both buyer and seller in one person. There would then be no market for means of production and no prices. Consequently, there can be no economic calculation. When should a means of production be replaced by a new one? This cannot be answered efficiently without prices. This argument was published in 1922 by the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises in his book “Socialism” [Mis49]. This problem, however, affects every monopoly, including large monopolistic corporations.

The Market

Supply and demand are brought together in a market. In the physical world, a market is usually a square in the city center where traders used to offer their wares. These marketplaces still exist in many cities, but most consumer goods are traded in supermarkets and department stores.

A market in the theoretical sense is a set of sellers, buyers, goods, and prices. There are different variants:

- A free market is not regulated—i.e., there are no restrictions by the state or others. There are not many of these left in the real world. But much open-source software is still free, such as programming languages and databases.

- In a regulated market, there are state requirements, such as:

- Only certain sellers are admitted (e.g., through licensing, like with taxis or banks).

- Only certain buyers are admitted (e.g., in wholesale).

- There are price specifications, such as price ceilings or price floors.

- There are ecological guidelines.

- Labor law: a business of a certain size must have a works council.

- In a black market, goods prohibited by the state are sold, such as weapons and drugs. Offers where necessary taxes and duties were not paid also count as part of the black market, such as smuggled goods or illicit work.

If you want to write an agent-based model for a simulation, a colloquial description of a market is, of course, insufficient. In their book “Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World,” David Easley and Jon Kleinberg introduce the mathematical and algorithmic theory of markets [EK10].

Matching market

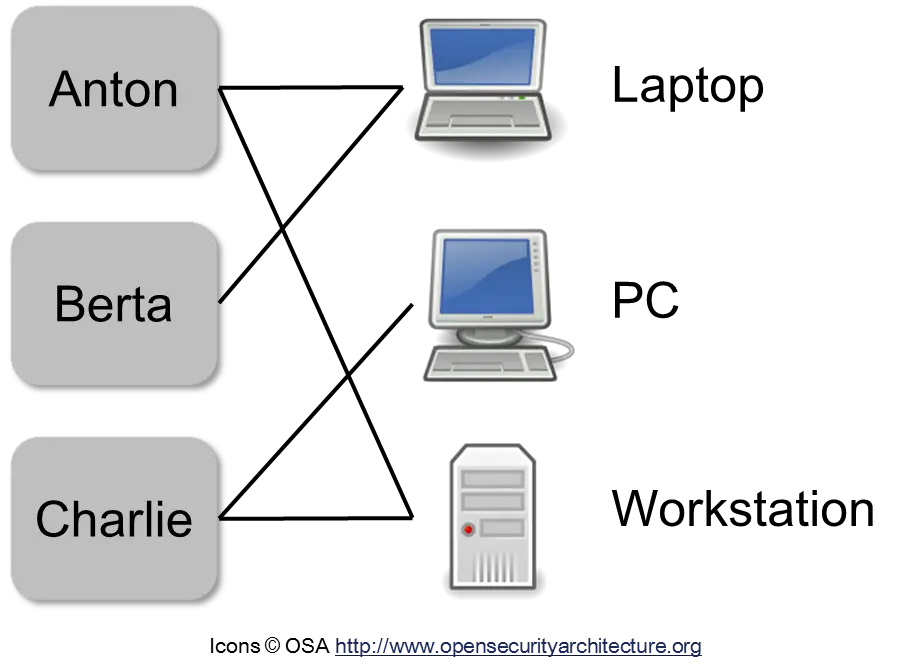

A “matching market” is the simplest possible example of a market. Let’s assume as an example that Anton, Berta, and Charlie have founded a startup and must share a laptop, a PC, and a workstation. But not everyone wants to work on every device. Everyone has their likes—their preferences. Anton, for example, would work on the laptop and the workstation, Berta only on the laptop, and Charlie on the PC or the workstation. In the following figure, the three people and the three devices are shown schematically.

The preferences are represented as (undirected) edges between the two nodes. Such a graph is called a bipartite graph because it has two different types of nodes (people and devices) and an edge always connects both types.

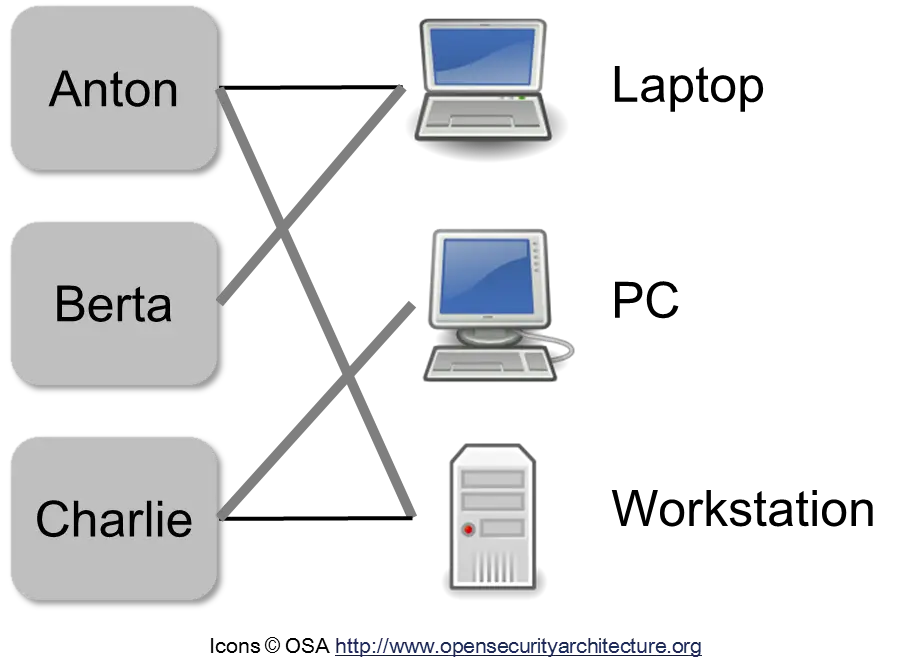

A “matching” is a solution that identifies an edge to a different device for each person—i.e., finds a device for every person. Many different algorithms have been developed in computer science for this purpose [CLRS09]. In the following figure, such a “matching” is symbolized by thicker edges.

Anton takes the workstation, Berta the laptop, and Charlie the PC.

“Matching markets” are the simplest imaginable markets. An algorithm for a simple problem can often be expanded. Such an expansion would be, for example, that one could order the preferences. Anton could then say, for instance, that he would rather work on the laptop than on the workstation. This turns a matching into an optimization problem. One wants to find not just any matching, but the “most optimal” one, so that as many people as possible can work on their favorite device. Algorithms have also been developed for this problem [EK10].

A Market with Prices

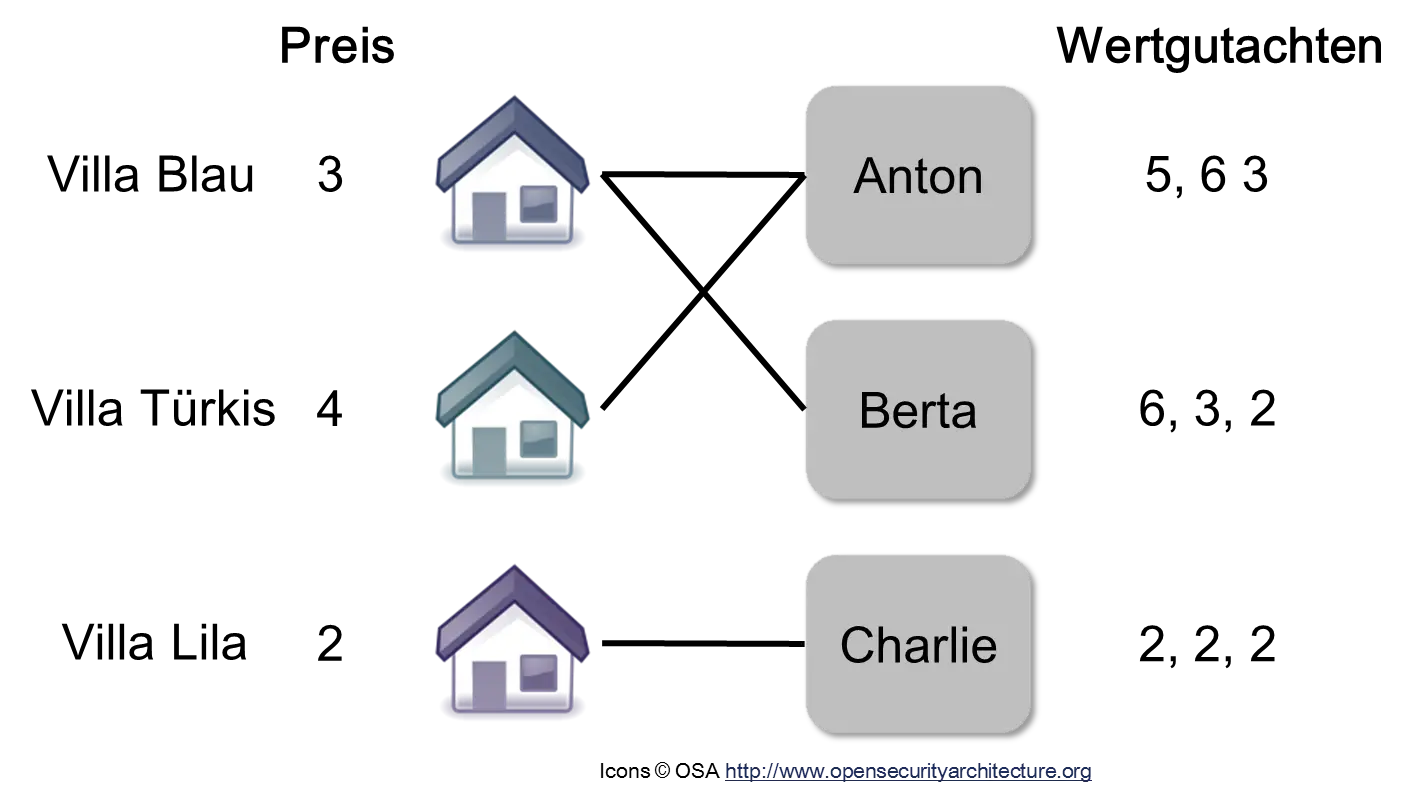

Another expansion is prices. For this, we use a different example (freely adapted from [EK10]): Anton, Berta, and Charlie were very successful with their startup, and now everyone wants to buy a villa. There are three villas to choose from: Blue, Turquoise, and Purple. Each owner of a villa specifies a selling price: Villa Blue for 3, Villa Turquoise for 4, and Villa Purple for 2.

For each house, Anton, Berta, and Charlie provide a valuation. Anton, for example, estimates the value of Villa Blue at 5, the value of Villa Turquoise at 6, and the value of Villa Purple at 3. Now, for each valuation, the difference to the asking prices is calculated. Anton estimates the value of Villa Blue at 5, while the price is only 3. He thus makes a “gain” of 5 - 3 = 2. For Villa Turquoise, it is also 6 - 4 = 2, while for Villa Purple, it is only 3 - 2 = 1. Therefore, Anton wants to buy Villa Blue or Villa Turquoise because the difference is highest there. This is why edges have been drawn between Anton and these two villas in the graph above. The same procedure is followed for Berta and Charlie.

Thus, the new problem is traced back to the known bipartite matching problem from the previous example. It is a common technique in computer science to trace new problems back to known problems for which a solution method already exists. An optimal solution for a “matching” is called a market equilibrium (“market clearing price”). In this case, Anton buys the Turquoise Villa, Berta the Blue Villa, and Charlie the Purple Villa.

Important: A market is an algorithm for solving the relationship between supply, demand, and price.

In the economic literature, there are countless insights about markets; for the interested reader, the book by Easley and Kleinberg is recommended [EK10].

Criticism of the Market Economy

Markets can thus be formalized and are an algorithm. Some critics speak of “market radicals” or “market radicalism.” This is just as nonsensical as speaking of “mathematics radicals” or “chemistry radicals.”

In political discussions, economic crises are often referred to as “market failure,” and this is usually associated with demands for “better” regulation by the state. Here, critics usually attribute a capability to the market that it does not have. For example, a market can only protect the environment if the environment is also “expensive.” If a company is allowed to simply cut down a rainforest for a low price, then that is a problem of the forest owner and not of the market. Why does the forest owner give away the wood so cheaply? Most likely, the owner is a state, because a company would sell the forest as expensively as possible due to profit orientation. This is an example of the “Tragedy of the Commons.” A market can also be immoral, such as the brokerage of contract killers or dangerous poisons. But that is not a problem of the market itself, but of the respective people who offer or buy such things. A market is the result of human actions and thus also reflects societal problems. This is no reason to question the functionality of markets as such.

It should also be emphasized that there are “markets” where payment is not made in money but through other social advantages, such as social prestige or sex. The dance floor of a nightclub is also a marketplace.

Profit Orientation, Bureaucracy, and Social Enterprises

Organizations

People organize themselves; they form groups and organizations. They have done this since the time of hunter-gatherers to increase their chances of survival. Later, settlements were added, then cities, empires, and nations. Today, there are also virtual economic and social networks.

In the economy, the most used form of organization is the company. Companies have many advantages over a loose organization of individuals [Mor07]:

- Complex goods can only be produced through collaboration.

- Mass production offers cost advantages; products can be manufactured more cheaply.

- People can work together better within a company because communication is more direct and because responsibilities and tasks are clearly defined.

- A company reduces so-called transaction costs. Theoretically, a company could be run by a single person who buys all required services from other firms. This would be cumbersome due to the many contracts and purchases and would also increase the price of products.

- Innovations may be worth millions of Euros and are therefore business secrets. These can be kept secret more effectively within a small, sworn community, such as a startup [TM14].

“Management” has established itself as a technique for managing such organizations. The organization is usually divided into specific parts, personnel are often organized hierarchically, and corporate goals are specified. There are many different possibilities in detail. Gareth Morgan’s book “Images of Organization” provides many perspectives from which one can view organizations [Mor07]. Previously, organizations were viewed as machines and consisted of individual departments connected via a centralized bureaucracy. They were highly hierarchical, bureaucratic, and mechanistic. Today, companies are seen more as organisms connected to each other via a kind of nervous system.

Profit-Oriented vs. Bureaucracy

In the past—put simply and somewhat provocatively—there were only the following two possibilities for the supreme organizational principle of an organization [Mis44]:

- Profit-oriented

- Bureaucratic

A profit-oriented company tries to have more income than expenses. The company can support itself financially and does not require subsidies or tax money. A “profit orientation” allows for a simpler structure of organization and “flat hierarchies” [Mis44]. Individual departments of a company can work independently as long as the individual departments are “profitable.” This makes it possible for company owners to say to the department head, “you can do whatever you want, as long as the numbers are right.” The department head is thus relatively “free” in their options.

An example of this is “franchising.” In “franchising,” licenses are granted for the use of business concepts [GFC13]. The franchisor owns the brand name, design, trademarks, and products and licenses them to the franchisee. The franchisee is usually an entrepreneur who is financially independent and takes full financial responsibility. The “franchising” business model also has the advantage of exploiting the fact that knowledge about local customers is available decentrally with the individual entrepreneurs. Thus, the service is likely better, and the employees are more knowledgeable.

Bureaucracy and bureaucratic methods are very old and exist in the administrative apparatus of all states whose rule extends over a large area. “Already the pharaohs of ancient Egypt and the emperors of China built giant bureaucratic machineries,” wrote von Mises [Mis44]. Bureaucracy is the organizational form of the “political means.” What could a king do in the past if he wanted to appoint a representative in a distant province? There was a danger that the representative would not be loyal and would “abuse his power.” The king therefore cannot tell him “do what you want” but must give him rules and regulations. State bureaucracy, according to von Mises, consists of the “appointment” of an official and the obligation to follow certain laws and regulations that he must strictly adhere to. In bureaucracies, the division of labor is organized via hierarchies and regulations. This leads, among other things, to bureaucracies being unable to change themselves and adapt to new conditions. A bureaucracy is “conservative” because every official is geared toward respecting the regulations and not questioning them. A bureaucracy is a complicated system, but not a complex one, because it lacks “bottom-up” processes.

Bureaucracy is the tool of politics. In a world with ever-faster technological progress, rigid bureaucracy will necessarily always lag behind and be unnecessarily complicated. In Germany, there are regular discussions about the “complexity” of a tax return; it is said that it must “fit on a beer coaster.” This will never happen because it can be changed neither “top-down” nor “bottom-up.” Many tax advisors earn their money precisely because of this artificial bureaucratic “complicatedness.”

However, bureaucracy also exists in today’s companies. As a rule of thumb, the larger the company, the larger the bureaucracy. Bureaucracy arises in firms also due to the fulfillment of legal requirements. These legal requirements cause costs that are charged to customers via higher prices or to employees via lower wages.

Social Enterprises

Profit orientation does not mean that profit must be “maximized,” that the environment is harmed, or that employees are exploited, as is often portrayed in the media. A profit-oriented company actually only needs to earn “enough.” An example is “Fair Trade.” Here, companies have emerged in recent decades that are profit-oriented on one hand but pursue specific social goals on the other, such as “fair pay for workers in the so-called Third World.”

The fact that “profit orientation” in today’s companies sometimes takes on such inhumane traits is also due to “capitalism without owners” [Gil13]. Most of today’s large companies are joint-stock companies (Aktiengesellschaften) that belong to no one and where, in the end, no one is really responsible. The employees of the AG can only become wealthy if they “extract” as much value from the company as possible, as managers do with their high salaries.

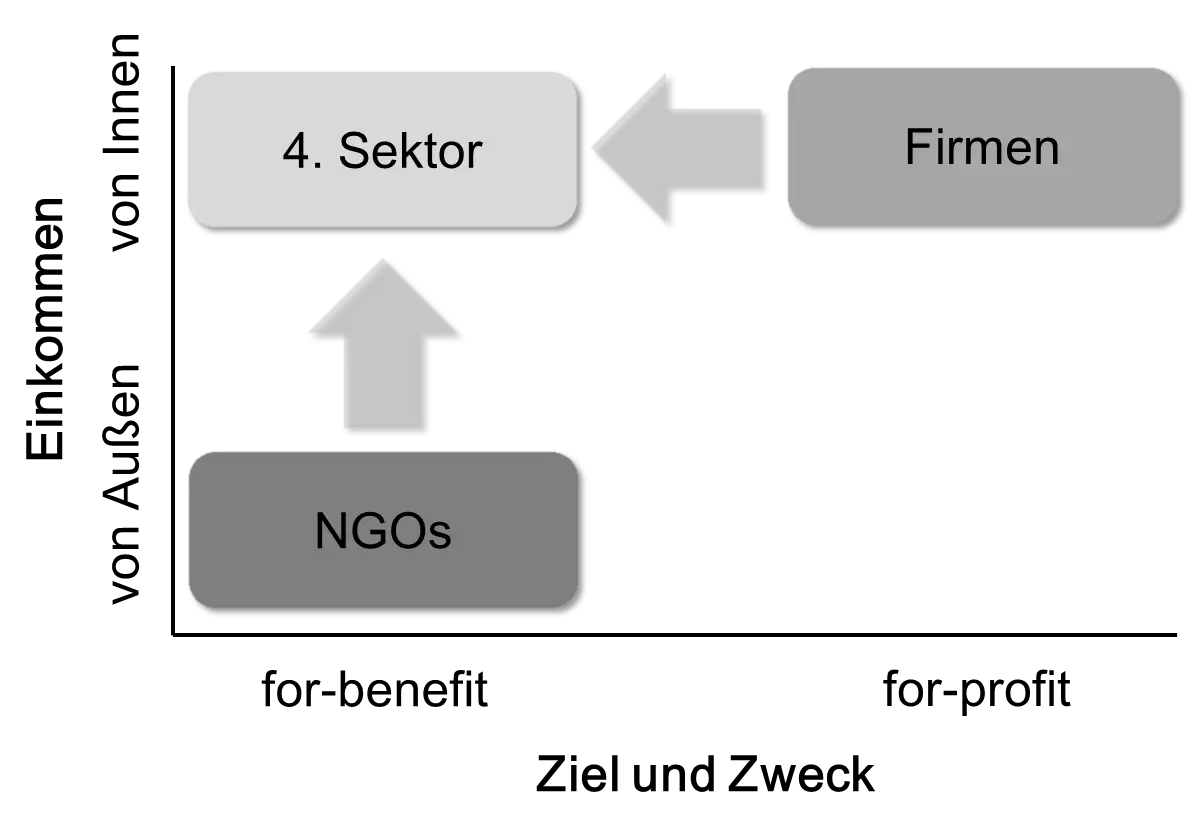

Profit orientation also does not mean that the profit must be a profit of money. An environmental organization can see its profit as the “protection of endangered species.” A social enterprise can see its profit as the “number of people with literacy skills” or as “what percentage of people can afford a medication.” In recent years, a new type of company has emerged here: the “for-benefit” company [CK14] and the so-called “fourth sector.” The following diagram shows the different types of organizations:

Many organizations derive their income, for example, through donations or taxes from the outside, such as so-called non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These organizations often have social goals and therefore do not practice profit maximization. However, they most likely then have the disadvantage of being very bureaucratic, and the money does not arrive where it is actually supposed to go. Traditional firms, on the other hand, are “for-profit” and derive their income from the “inside”—i.e., they generate it themselves—but have no social goals.

The so-called “fourth sector” (the first sector is the state and is not shown in the diagram) consists of “for-benefit” companies that generate their own income—meaning they are profit-oriented but not profit-maximizing1. They are a mixture of NGO and company that aims to combine the advantages of both. Such a “for-benefit” company must legally commit explicitly to the goals to be achieved. Examples of such goals are “production of a drug that 95% of the population can afford” or “internet access for 99% of people.”

However, the necessary legal framework is still missing in many countries to ensure that capital cannot simply be extracted from these firms and they are thus converted into “for-profit” companies. In the USA, experience has been gathered with this form of company since 2010 [CK14]. A task for politics would therefore be to take care of the legal foundations for “for-benefit” companies instead of conducting “political debates” about information technology.

Evolution and Dynamics

The world is constantly changing. Companies develop new products, researchers make new inventions, musicians write new songs, poets write new poems, people change their tastes and habits. The world is dynamic. Heraclitus of Ephesus (520–460 BC) expressed it thousands of years ago: “everything flows” (“panta rhei”). As we will learn in the rest of the book, however, everything flows faster today than before, and in the future, it will flow even faster.

People make new technical inventions, which in turn can trigger new social inventions. The telephone, for example, has changed the social behavior of people. A factory is the expression of a society’s current state of knowledge about technology, management, psychology, and process organization. Technology influences social and economic life and vice versa.

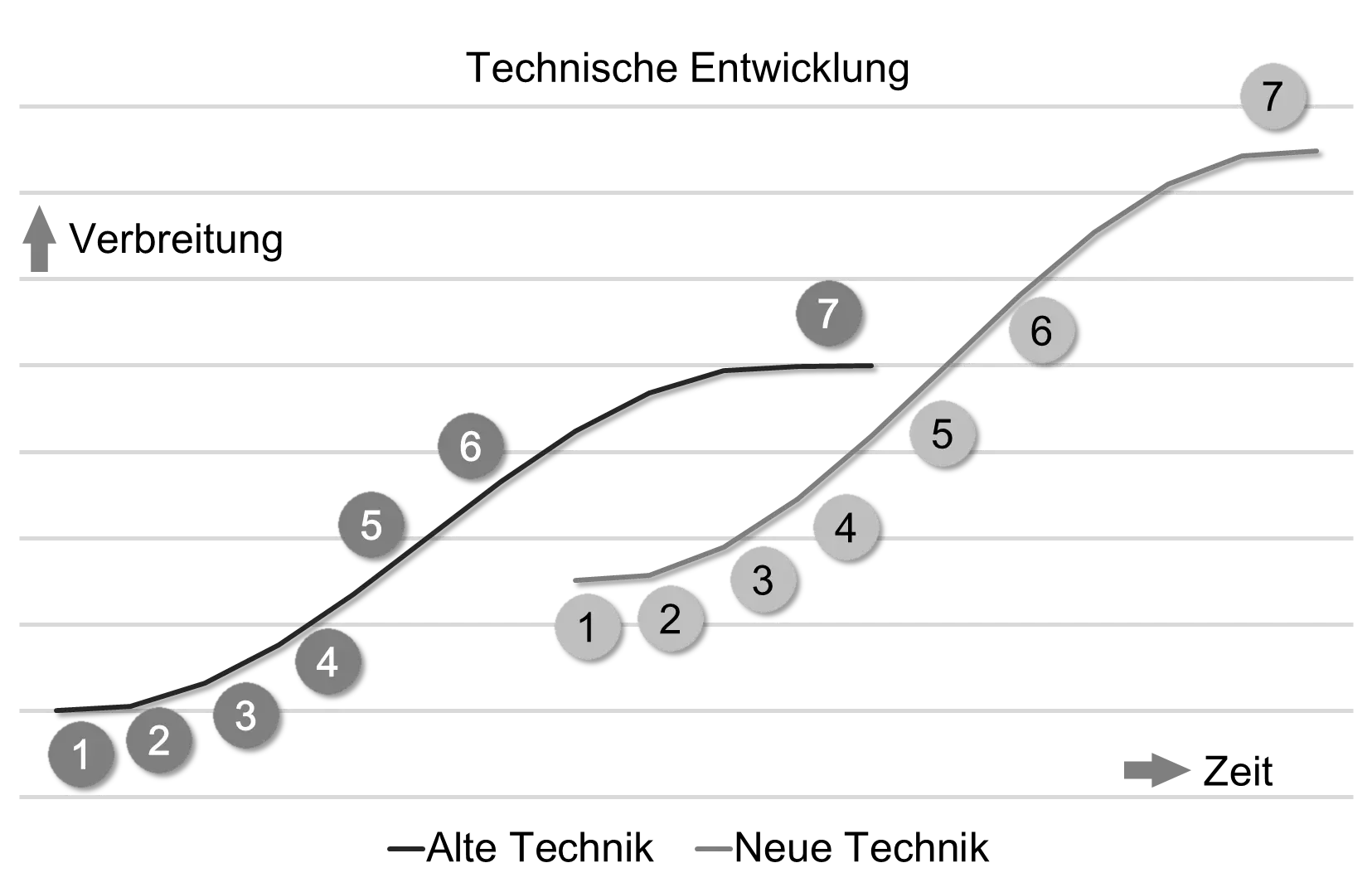

Inventions differ in their influence on general life. There are inventions that change life very strongly, such as the internet. And there are inventions that affect only a small part of humanity, such as a method for faster production of East Frisian rock sugar (“Kluntje”). An invention with very large effects is called a general purpose technology (GPT). Examples of this are the steam engine, electricity, and information technology (IT). A general-purpose technology is often not very useful on its own but requires further complementary inventions that supplement this technology. People must first find out how to best use these new inventions [BA14]. Therefore, the introduction of a new invention follows a so-called S-curve, as shown in the following figure:

In the diagram, a new technology replaces an older one. The development has the following phases [Kur06]:

- Dreamers: people dream of the new technology—”wouldn’t it be nice if…”

- Invention

- Development: a product must be made from the invention that is manufactured in mass production.

- Maturation: the technology is gradually improved.

- The technology threatens the old technology, but something is still missing.

- Takeover: the technology takes over the market.

- Antiquity: the technology is obsolete and only something for enthusiasts, such as vinyl records today (approx. 5–10% of lifespan).

The history of technology is an evolutionary process of successive S-curves. Each phase creates better “tools” for the next phase [Kur06].

Crucially, society must also be able to adapt to the new possibilities. If politics, for example, bans the use of new robots or makes them more expensive, then development is delayed [BA14]. Today, many companies from the so-called sharing economy, such as Uber or Airbnb, are very controversial. Many established companies demand political action against the new competition.

When something completely new is found in a science, such as the theory of relativity in physics, one speaks of a “paradigm shift,” which also follows such an S-curve [Kuh12]. During a paradigm shift, a large part of previous knowledge is replaced because it no longer agrees with the new paradigm. During a paradigm shift, there are also heated discussions in the sciences between established scientists of the old paradigm and the “innovators.” Since science takes place mainly in state universities and research institutions and is organized bureaucratically and hierarchically, the “new” have a much harder time here than in a market economy. In a market economy, they can do their own “thing” and found a startup, while in the university system, one only moves forward if it has been sanctioned by hierarchical superiors.

Innovations through Collective Intelligence

There are various theories about how innovations arise. The most plausible is the theory of combinatorial innovation [BA14]. According to this, innovations arise through the new combination of already known parts. This “combination” is usually not trivial, and finding it can require a lot of work.

An “inventor” today is usually no longer a single person working alone in a “quiet” room, but a group of specialists who share their knowledge. In an invention, known parts must be reconnected: a database, a web server, an app for mobile phones, etc. The internet is used for the exchange of ideas. If a technical term is unknown, it is googled. If the database gives a strange error message, one looks at the manufacturer’s service portal or an open-source portal.

The more of these “inventors” have internet access, the more inventions can be made. The more inventions that have been made, the more building blocks there are for further inventions. Here, growth accelerates. Humanity is a networked problem-solving process. A “collective intelligence” has emerged [Hin13, BA14].

Complex Economics

Once you are familiar with complex systems and agent-based modeling, economics no longer appears to be at the current state of the art. Many mathematical-economic analyses use the equilibria derived from physics. If you look at a typical introduction to economics, such as that by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells [KW05], you are initially amazed that the economy is treated only from a bird’s-eye view and is more of a statistical science than a causal science.

But this will likely not be the case for much longer, because economics is at the beginning of a paradigm shift: through the theory of complex systems and agent-based modeling, economics in the 21st century is set to become a “real” science: complexity economics [Bei07, Art14, CK14].

According to Eric D. Beinhocker, this “paradigm shift” should proceed as quickly as possible because it has great consequences [Bei07]. Many previous findings in economics, politics, and society are at best only approximately correct, and many parts are wrong. Politics therefore often causes more damage than making useful decisions. According to Beinhocker, new economic theories have always triggered major changes in practice: Adam Smith, for example, led to free trade and the Industrial Revolution. Karl Marx led, on the one hand, to revolutions and the socialism of the Soviet Union (Marxism-Leninism) and, on the other hand, to the welfare state and social democracy. For example, the German party SPD named “democratic socialism” as its goal in its 2007 “Hamburg Program” and describes “Marxist social analysis” as one of its roots [SPD07]. The neoclassical theories of the last half of the 20th century led to today’s globalized “casino capitalism” [Bei07].

The following table summarizes the differences between complex and traditional economics:

| Complex Economy | Traditional Economy | |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamics | Open, Dynamic, Non-linear | Closed, Linear, Equilibrium |

| Agents | Individuals, Incomplete Information, make Mistakes, Adaptive, Learn | Collective, perfect Rationality, complete Information |

| Networks | Explicitly defined | Implicit, e.g., Auctions |

| Emergence | Yes | Micro- and Macroeconomics are different subjects, Emergence is interdisciplinary |

| Evolution | Possible through Differentiation, Selection, and Reinforcement | No Changes |

Economics is therefore also facing major changes. Due to the previously mentioned “Twin Peaks” problem, however, these changes will likely take place rather slowly. But they will take place. Because the theory of complex systems and the “bottom-up” perspective of agent-based modeling allow for a better view of reality than the differential equations used hitherto.

-

See also http://www.fourthsector.net/. ↩