Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

The History

Trade, Technology, and Social Institutions

Exchange Leads to Trade

Ötzi lived about 5,300 years ago during the Copper Age in the Ötztal Alps. He was 1.54 m tall and died at approximately 45 years of age. Ötzi possessed an axe made of 99% copper. This copper originated from the Salzburg region, about 200 km away from where he was found. Ötzi also had a dagger with a flint blade and an ash wood handle. Embedded in the flint are fossils that only existed in the Lake Garda area, at least 100 km away. A high concentration of metals was found in his hair, leading to the assumption that he came into contact with copper processing. The processing of copper is so labor-intensive that one cannot perform other tasks on the side, let alone grow food [Rid10].

What does this tell us about Ötzi’s world?

There must have been trade and specialized “copper producers” who possessed the necessary tools for manufacturing and processing. Ötzi’s society was therefore already developed and familiar with specialization, division of labor, trade, and exchange: a type of “market economy” already existed 1.

In his book “The Rational Optimist”, Matt Ridley explores the question of what the most important human invention was [Rid10]. What caused human success? How did progress emerge?

It is voluntary exchange! Only when humans “figured out” that they could exchange goods with others, and that both benefit from it, did they truly distinguish themselves from animals. Apes, such as chimpanzees, understand mutual aid according to the motto “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” (“Tit for Tat”). If one chimpanzee grooms another, the other will groom him back [Fre14, Rid10]. This behavior is called reciprocity. However, scientists have found that apes cannot trade. They lack the “logic” for it. An ape can exchange a non-edible object for something edible. But he cannot exchange an edible item he likes less for another edible item he prefers more. He lacks this “intelligence” [Rid10].

Voluntary exchange is what first enables the division of labor. People can “specialize” in certain professions and still survive because the economic network allows them to trade their goods. Ötzi was able to acquire a copper axe and a flint knife from a “toolmaker.” Without this exchange, only life at a subsistence level is possible. Everyone must “hunt and gather” their own food and cannot build specialized knowledge because there is no time for it. Without the division of labor, no progress is possible [Rid10].

Voluntary exchange between two people is positive for both; it is a win-win situation. Person A has too much of X and wants Y; person B has too much of Y and wants X. Thus, the two can agree to exchange X and Y with each other. The ratio of how many X person B receives for one Y is the price. The value is established through the exchange. It is a subjective value [Mis49]. Each person determines, based on their personal preferences, whether they benefit from the exchange: “What would I rather have? 3 X or 2 Y?”.

The fact that prices are subjective and not objective was first investigated by the economist Carl Menger (1840 - 1921), who is considered the “founder” of the so-called Austrian School. Many other economists, such as Karl Marx, still believed in an objective value of goods and labor at that time. However, they faced significant difficulties because they could not satisfactorily explain many questions. Why do some people pay huge sums of money for famous paintings? Because they are inherently worth it? Or because there are people who find them that valuable?

From Trade to Prosperity

The “invention” of exchange and trade did not remain without consequences. The following figure shows the development in a simplified form:

Through the “invention” of exchange, trade became possible. People can divide labor among different individuals. This allows people to focus on one task—to specialize. These “specialists” then discovered things no one before them had found, because no one else could previously invest so much time into one field. New products, such as copper axes, emerged and progress was born. Consequently, people were much more successful together than they would have been alone. The entire society becomes “wealthier.” Most people are better off together than alone. Prosperity is the ability to use the products and services of others, even if one does not know how they are produced. In the words of Matt Ridley, a “collective and cumulative intelligence” emerged, characterized by trade and the division of labor through specialization.

Technology and Social Development

Specialization leads people to improve their craft and their tools—in other words, their technologies. Many technical inventions have major impacts on society. Technical inventions are often followed by “social inventions.” Examples include the printing press or the internet. The internet enabled social networks, through which the world has become a “global village” and, for instance, helped initiate the “Arab Spring” in 2011.

There are also inventions that are not technical, but purely social. Many social norms and values are “inventions.” One example is the so-called Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Other examples include the rule of law, democracy, credit, respect for property, and a free press. These social inventions are no less important than technical ones [Rid10]. On the contrary, without a stable society with a certain “order,” the economy cannot exist. The word “order” is often associated in German with authority, the Empire, or a dictatorship. This type of “order” could be described as “top-down” order and is not what is meant here. There are also norms and rules that emerge “bottom-up” in society, which can also be understood as “order.”

Progress thus happens through technical and social inventions. But how can progress or civilization then be measured? Has the world become better? Has there really been progress? Or is the world on a declining course? If you want to evaluate something, you must have a comparison criterion. The British historian Ian Morris developed such a criterion in his book “Why the West Rules—for Now”: the “Social Development Index” [Mor11, BA14]. For this, Morris collected a vast amount of data and compared Western civilization with Eastern civilization. The index is intended to express how well a society could master its physical and intellectual environment and consists of the following attributes:

- Energy Capture:

- How many calories can a person obtain for food?

- How much energy is available for labor, trade, industry, transport, and agriculture?

- Social and Economic Organization:

- The size of cities and organizations.

- War-making Capacity:

- Number of troops, weapons, logistics.

- Information Technology:

- The available means for information processing.

- And how these were utilized.

Morris “quantified” these four traits—i.e., expressed them as numbers—and combined them into the aforementioned index. Morris then uses this index to compare different civilizations. While interesting, this is not critical for this book. What matters here is that a historian has understood how important information technology truly is.

Important: Information technology is a fundamental factor for civilization and progress.

This historian does not speak of a “technological totalitarianism,” as some German “intellectuals” and politicians do, but understands the importance of IT [Sch15]. The reason IT is so important is not because some “capitalists” desperately want to make money, but because IT fulfills a vital function. The topics covered in this book are therefore important for progress. A “political debate” and political interference can thus become a threatening matter if politics sets the wrong course here.

Important: Incorrect regulation of IT will likely have fatal consequences.

The Economic Means

Theory of Constraints

The factors of production of a product or service are everything required to produce that product or service. They are the “ingredients” or the “input.” These include, for example, knowledge, capital, time, labor, and land. The Israeli management consultant Eliyahu M. Goldratt (1947 - 2011) described in his “Theory of Constraints” that in organized labor, such as in a factory, there is always a bottleneck (“constraint”) that prevents faster or better production [GC12].

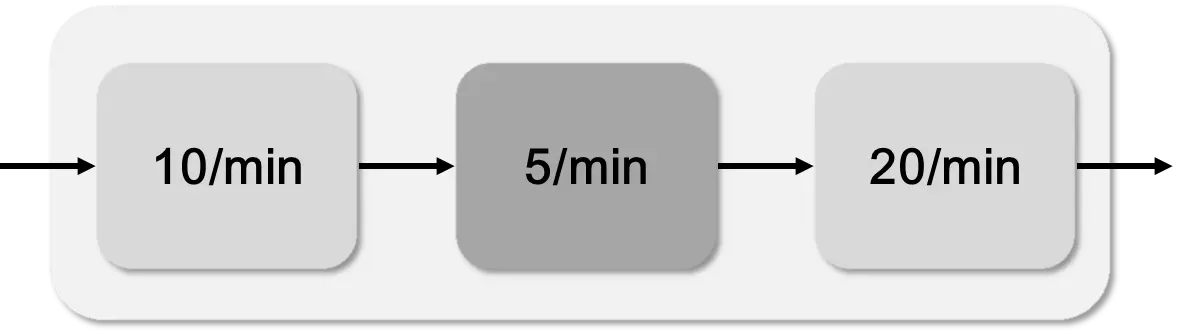

The following figure represents, very abstractly, a part of a factory with three machines.

The first machine can process 10 units per minute, the second 5 per minute, and the third 20 per minute. The bottleneck here is the machine in the middle and is therefore highlighted. In this example, it is child’s play to find the bottleneck. In reality, this is naturally not so simple in production processes. Because these—as we already know—form a network and not a simple chain.

The bottleneck is the limiting factor that restricts the entire system. There are two options here: Either you improve the throughput of the middle machine to 20/min. Then the first machine becomes the limiting factor. Or you accept the 5/min and adjust the first and last machines, replacing them with cheaper machines with a speed of 5/min. This would reduce costs.

Improving such a process is also called process optimization. The important insight here is that in such process optimization, you only need to worry about the bottleneck. Improving the other parts would be a pure waste of time. There are thus three important questions [Pea15]:

- What does the system look like?

- What is the limiting factor?

- What is the best way to improve this limit?

This sounds very simple, like something from a children’s book, but in practice, it apparently is not; otherwise, Eliyahu M. Goldratt would not have sold more than 6 million copies of his book “The Goal”.

The Evolution of Bottlenecks

Management consultant Ron Davison used the “Theory of Constraints” to examine human history. In his book “The Fourth Economy”, he described history as a history of bottlenecks in production factors [Dav11]. The following table presents the history of production factors:

| Era | Limit | Economy | Intellectual | Institution | Upheaval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1300–1700 | Land | Agriculture | Renaissance | Nation-state | Religion |

| 1700–1900 | Capital | Industrial | Enlightenment | Bank | Politics |

| 1900–2000 | Knowledge | Information | Pragmatism | Large corporations | Financial industry |

| Since 2000 | Entrepreneurship | Entrepreneurial | Systems thinking | Individual | Business |

In every age, there was a “limit,” the limiting production factor, and corresponding institutions and organizations that utilized this production factor. Because everyone needed this limiting factor, it often became scarce, leading to struggles and wars over it. Due to technological and social progress, the limiting production factor changed. Then a type of phase transition occurred, where the dominant institution also changed.

Today, all factors are still required. However, economies in individual regions use different proportions of these factors. There are parts of the world that still depend heavily on agriculture. Other parts, such as major cities and metropolitan areas, depend more on capital and knowledge. Silicon Valley, on the other hand, also requires many business founders, so-called “entrepreneurs”.

The following journey through history was created using various sources [Dav11, Pea15, BA14, Rid10, Wri01] and Wikipedia.

Land

Let’s take a small leap back in time to the first age, when land was the primary factor of production. Agriculture was still simple and technology very basic. The factors of production were land, physical labor, and for some farmers, an ox for the plow. If no plagues or other diseases occurred, there were always enough people. Therefore, land was the limiting production factor. The more land someone controlled, the wealthier they could become. Thus, rulers were interested in expanding their land holdings as much as possible. It was the age of the discovery of America, the search for land and natural resources, and conquest and plunder through colonialism.

The Catholic Church was the dominant power. But this power was crumbling. In England, Henry VIII reigned. He was unable to produce a male heir with his first wife. He wanted to marry his mistress Anne Boleyn, who was pregnant. When the Catholic Church refused him a divorce, he started the English Reformation and founded the Church of England. He made himself its head and expropriated the Catholic Church, having all monasteries looted and demolished. The new dominant institution, the nation-state, abolished the old dominant institution, the Church. Power became secular.

Henry VIII then laid the foundation for England’s further development with new economic laws. He abolished internal tariffs, standardized weights and measures for better trade, established legal certainty for property, and limited trade restrictions. More trade enables better division of labor and specialization and generates—as we have seen—prosperity. In 1545, he also allowed interest, which was forbidden according to the Catholic Church and the Bible. This was the foundation for England’s rise to become the leading nation, which it remained until the First World War in 1914.

Interest—as a brief note here—expresses the relationship of money at two different points in time. Money is worth X today and X plus interest in one year. If someone has money worth X today, they could invest it themselves—for example, by buying stocks—and thus make a profit of X plus profit in a year. If they lend the money to someone else, they forego this profit and want interest instead. Interest expresses the sacrifice of having money in the present. Today, however, the financial system is heavily regulated, as will be explained later in Section 11.3.

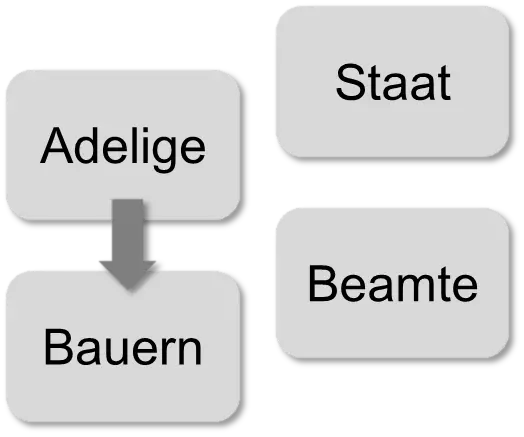

Germany was—compared to England—fragmented, inconsistent, and economically handicapped by small-state politics. The Reformation, initiated mainly by Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and John Calvin starting in 1517, led, among other things, to the Thirty Years’ War from 1618 to 1648. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 was an important milestone for the transition from religious power to secular nation-states, as the Pope was partially stripped of power. Due to Martin Luther’s “Two Kingdoms doctrine”—that the spiritual and secular should be separate—the Church continued to lose secular power over time to the rising nation-states. The economies of these states were mainly based on land ownership and natural resources. This led to the age of colonialism. Very simplified and abstracted, society had the following structure:

The state was managed by “civil servants.” The land was mostly in the hands of aristocrats and was cultivated by peasants. The influence of the Church began to decline. Of course, there were also craftsmen, bakers, blacksmiths, etc., back then, but this is intended to be a very simplified model.

Due to technological development, however, agriculture was slowly pushed back by craftsmanship and trade2.

Capital

In the period from 1500 to 1750, the economy was dominated by so-called Mercantilism. People believed at the time that there were advantages to “steering” the economy through extensive state intervention. In Mercantilism, there was a so-called guild for every profession. A guild was a type of interest group and strictly regulated the respective profession. Among other things, the number of authorized providers was fixed to keep supply artificially low and prices artificially high. Jews were often forbidden from joining guilds, so they had to seek out new professions. They were forced into innovation. Due to the ban on interest, Catholic believers and even Catholic princes and kings were forbidden from taking interest. Jews, however, were allowed to do so and therefore founded banks.

From 1700 onwards, there were many technical inventions. The Industrial Revolution was slowly announcing itself. However, Mercantilism was bad for the economy. The economy is a complex system and impossible to “steer.” On the other hand, nation-states even then were not good with money. Therefore, nation-states often needed loans from banks. Today, there are central banks—the FED in the USA or the ECB in the EU. With these, states can indirectly “print money for themselves” through convoluted paths. Back then, however, they were still dependent on real bankers. The most famous example is the Rothschild family. Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777 - 1836), for example, financed the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington during the Napoleonic Wars by purchasing British government bonds. These bonds were then sold within the widespread family in Vienna, Frankfurt, Paris, etc. Thus, the wars of the nation-states made the Rothschild family rich [Rid10]. The Rothschild family was an “entrepreneur.”

Even the Prussian King Frederick William III had to borrow money during the wars against Napoleon. What is historically special about this is that Nathan Rothschild made it a condition for a loan that reforms had to be implemented after the war. So, it worked according to the motto “You only get the money if…”. A banker was giving orders to a king; that was something completely new. The banks were in power. Capital became the limiting factor of production, and the era of “Capitalism” had begun.

Important: Bankers became wealthy because they financed nation-states. Because states went into debt, banks could profit from it.

Technologically, it was the time of industrialization and great changes. James Watt (1736 - 1819) had improved the steam engine by 1769 to the point that it could be used industrially [BA14]. Previously, one was dependent on the power of animals and humans. Now there were factories, mass production, and railroads. The standard of living for people rose tremendously. This, in turn, created strong population growth. Previously in human history, this had always been a recipe for disaster. Thomas R. Malthus (1766 - 1834) was the first to investigate the problem of “overpopulation.” Every society that had strong population growth subsequently had problems feeding all those people or having enough energy for them, e.g., in winter. But for the first time in history, enough energy was available to prevent mass starvation: there was enough coal that could be processed into energy in steam engines [Rid10]. On the other hand, this naturally caused great pollution, but “alternative” energies had not yet been invented. And people in the past thought only of their survival.

Due to the many inventions, there were numerous changes. And not all parts of the economy changed equally. Some parts were legally protected against technological innovations and changes. There were winners and losers. The losers usually demand a ban on the new or at least a reduction.

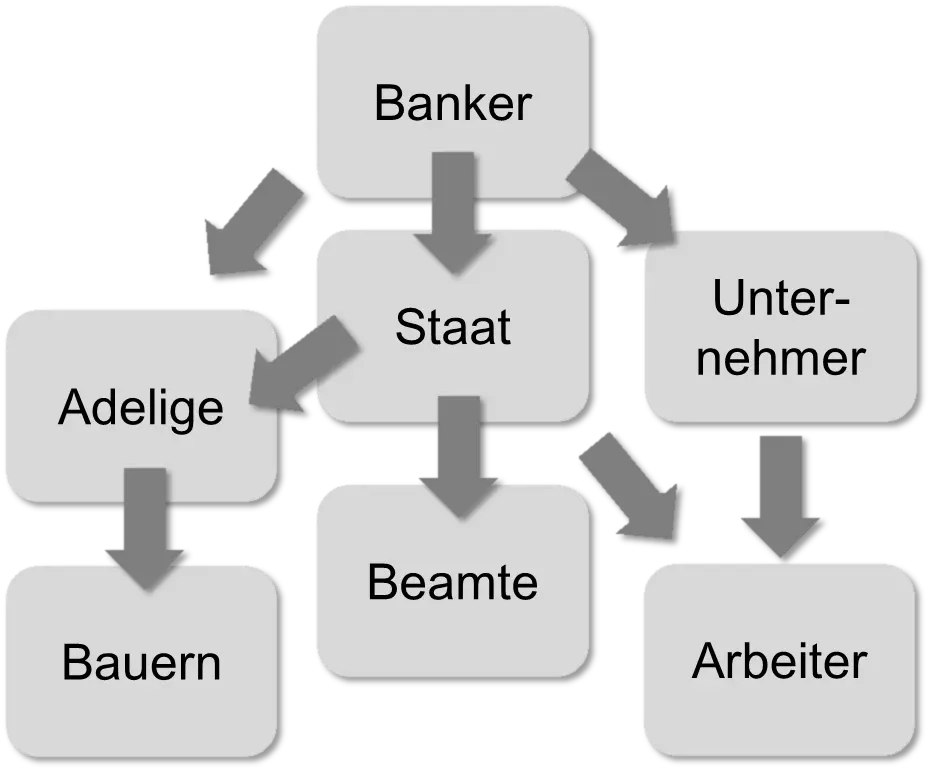

In a society, those who possess the most important production factors determine the rules. In the first age, when land was the most important factor, it was the large landowners—i.e., the aristocrats—whose land was worked by peasants. The aristocrats lost influence to bankers and entrepreneurs when capital became the limiting factor. The entrepreneurs, in turn, employed workers in the factories. Society now looks simplified like this:

And we can already see that society has become more “complex.” Bankers had varying degrees of influence on the other groups. But they were important for everyone because they could lend capital. It is important to see here that the aristocrats, the bankers, the state, and the entrepreneurs were in a competitive situation. Power was distributed among these “interest groups.” And there were, of course, bitter “fights” between these groups.

While technological progress was immense, operating a factory did not yet require much knowledge. One could buy machines and simply copy production processes. It was truly the era of “Capitalism,” as capital was the most important factor of production. Looking back today, industrialization is often described negatively: child labor, pollution, and exploitation. It is also disparagingly referred to as “Manchester capitalism” (often by Germans with a tone of envy because Great Britain was far ahead at the time). Of course, conditions were worse than today; this is easily seen by looking at the key factors of Ian Morris’s “Social Development Index.” But people were often better off than before industrialization, and there were significantly more people than before [Rid10]. Unfortunately, photography only emerged with industrialization, so humanity has no objective way to compare it with the pre-industrial era.

A worker’s working conditions and salary are determined by his “productivity.” Productivity expresses what value is created in a certain amount of time. However, this productivity depends on society as a whole. A worker can only be as productive as the machines that support him. The factory depends on traffic connections and transport options, the number of qualified workers, etc.

Important: Increasing productivity is an “economic network problem.”

And workers’ conditions were very poor from today’s perspective because productivity was also still very low. An example of improving conditions for workers was provided by Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856 - 1915), who was the first to begin studying and improving workers’ workflows in detail [Dru94]. Today, we would call it “increasing worker productivity.” If workers can accomplish more with the help of machines or through better workflows or conditions, they can also be paid more. Taylor called his method “Scientific Management,” and his goal was for workers to benefit from productivity improvements.

At this time, however, various “counter-movements” also formed, aiming for a better society and economy than “capitalism.” These “counter-movements” mainly had an unconstrained vision and tried to solve the economic problem using political means. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote the “Communist Manifesto” in 1848, for example. Marx and Engels divided society into two classes that stood opposite each other and had different interests: the “capitalists” and the “proletariat” made up of workers and peasants. Unfortunately, they overlooked the roles of the state, the workers, the entrepreneurs, the aristocrats, and the innovators here. A reduction to two classes is not a correct model of the society of that time.

Knowledge

But progress made further progress. In the second half of the 19th century, electricity and internal combustion engines emerged. And during the 20th century, the “complexity” of companies, products, and manufacturing processes steadily increased. Simple factories with simple machines became complicated facilities. Karl Marx still feared that workers would become “stupid” because they had to perform increasingly simple tasks. However, due to technical progress, complicated machines emerged that required a fair amount of knowledge to operate and repair [BA14, Rid10].

Finally, knowledge became the limiting factor. Management consultant Peter F. Drucker proclaimed “Post-Capitalism” in 1994 [Dru94]. Capitalism was over. As the starting point, Drucker cites the “G.I. Bill of Rights” of 1944 in the USA, which gave soldiers returning from the Second World War the opportunity to study. Thirty years earlier, after the First World War, this would have been unthinkable because there weren’t even enough jobs for people with degrees. Another milestone happened in 1975 when the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) simply switched banks for a large transaction. This was a sensation at the time. Today, companies compare bank offers and choose the cheapest for each transaction. Companies have now attained a higher standing than banks. In the competition between interest groups, companies had caught up with banks. Knowledge had replaced capital as the limiting factor.

We live not only in a “knowledge and information society” but also in a “knowledge and information economy.” Of course, there are still “capital-intensive” industries where capital is more important than knowledge. Land is also still needed for agriculture. However, knowledge became the limiting factor. Digitization and the internet have further amplified the importance of knowledge. Facebook, for example, is now worth billions of dollars but started with only $500,000 in external debt capital. That is less than the price of a condominium in a good location in a major German city. You can therefore earn a lot of money with little capital and the right knowledge.

Entrepreneurship

How to turn knowledge into money—or how to translate knowledge into concrete products—is the task of the company or the entrepreneur. The first signs of the importance of business startups were also provided by Peter F. Drucker in 1985 with his book “Innovation and Entrepreneurship” [Dru85]. The word “entrepreneur” is often used in different ways. For Peter F. Drucker, a businessman is an “entrepreneur” if he does something valuable and new. In his view, an entrepreneur does not have to be a small business; as an example, he also mentions the fast-food chain McDonald’s. According to Drucker, an entrepreneur also does not have to have commercial intentions, as he also includes Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767 - 1835), who “invented” the modern university in 1809. An existing company can also act as an “entrepreneur” if it “invents” something and brings it to market. An “entrepreneur” is thus an “inventive” businessman or an “inventive” company. The word “entrepreneur” sounds slightly snobbish in German, however. Yet, even the word “Unternehmer” (businessman/entrepreneur) has a negative connotation in Germany. It is associated with wealthy men sitting in executive suites in large office chairs, dressed in suit and tie. That sounds too little like innovation, inventive spirit, experimentation, and garage startups. Was Steve Jobs a businessman or an entrepreneur? The first Apple computer was built in a garage. This “entrepreneurial spirit” is not captured in the German word “Unternehmer.” Since there is no better word in German, “Entrepreneur” is also used in this book.

According to Ron Davison, “entrepreneurship” is the bottleneck among production factors in the USA today [Dav11]. Knowledge is still scarce, but not as scarce as “entrepreneurial knowledge.” Logically, this is not 100% clean, because “entrepreneurship” is knowledge about companies and therefore a subset of “knowledge.” But there is a certain truth in it. In Southern Europe, for example, in Spain and Greece, there is high youth unemployment today. Jobs are missing here. Existing companies must create new jobs, or new companies must emerge. There are only two possibilities here: Either it is too difficult to start a company in these countries due to legal requirements, or there is a lack of people with knowledge in “entrepreneurship.”

In Germany, there are several very strong international companies that contribute greatly to economic output. According to journalist Olaf Gersemann, in 2013, the three companies BMW, Daimler, and Volkswagen alone contributed a good quarter of the profits of the 30 DAX corporations, around a third of the sales, and nearly half of the expenditures for research and development [Ger14]. In Germany, therefore, large parts of the economy still function without “entrepreneurship.” The large companies pull a lot of people along. In other countries, where successful large companies are missing, this is not the case.

“Entrepreneurial knowledge” cannot be taught purely theoretically at universities or schools. Practical experience is necessary. It is also important that society allows for failure. In the USA, many business founders are only successful with their third or fourth startup. They try out several business ideas until one works. In many countries, including Germany, the importance of “entrepreneurship” has been recognized. However, focus here is often on support with capital (so-called venture capital) or support with legal issues. But the limiting production factor is “knowledge about entrepreneurship.” In school in Germany, you do not learn how to start your own business, but only how to become a good employee or worker 3.

-

More information about Ötzi: http://www.mummytombs.com/main.otzi.html. ↩

-

Land today plays only a minor role in politics in Germany. When a “wealth tax” is mentioned, real estate is usually not included. For socialists and communists, land reform was a primary goal before 1918. A fair distribution of land was to be achieved. This did not happen in Germany after both wars: not in 1918 and not in 1949. This is an indication that land was no longer seen as an important factor of production. Today in Germany, large landholdings are even indirectly subsidized in the context of alternative eco-energy: with each wind turbine, one can earn a lot of money through artificially fixed electricity prices. The more land someone has, the more wind turbines can be built. From this perspective, green electricity is therefore not “socially just” at all. ↩

-

In Germany, it was discussed in 2015 whether a subject “Economics” should be introduced in schools. Immediately there was an outcry in the media. The trade unions said “Social Science” would be more important. But if economics is not taught in school, then economic knowledge is “inherited”, i.e., passed on from parents to children. Children from “economically ignorant” families do not learn it in school and also not in the family. This results in greater disadvantage. ↩