Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

Artificial Intelligence

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Examples

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has set itself the goal of creating “intelligent systems.” The name was first used in 1956, and since then, AI has been surrounded by myths and controversy. On one hand, some predict a paradise on earth, a utopian future without worries where intelligent robots provide everything for humans. On the other hand, there are people who see Artificial Intelligence as the personification of evil and fear the end of humanity. Throughout this chapter, it will become clear that both sides have strayed very far from what is technically feasible.

But even if AI cannot yet create truly “intelligent systems,” many useful intermediate products have already been developed [RN10, BA14]:

- Self-driving cars, trains, and subways

- One can dictate letters to computers

- Texts can be translated into other languages with medium quality

- Vacuum cleaning robots clean households

- In 2007, IBM Watson won a game show in the USA

- In 1997, the computer Deep Blue defeated a chess grandmaster

Rational Agents

In AI, the term “agent” is also used. However, here an agent is not part of a simulation or a model, but a robot, a computer system, a program, or another machine [RN10]. An agent lives in an environment and perceives information through its sensors. With its actuators, the agent can interact with the environment.

If the agent is a computer program, the environment could be, for example, a single computer, a home network, or the internet. As sensors, the agent could, for instance, measure the room temperature with thermometers and use its actuators to regulate the heaters accordingly. Such an agent, which only controls heaters, would of course no longer be called intelligent today.

An agent could also be a computer program that searches the internet for specific things. As a sensor, it would then have a type of web browser, and as an actuator, it could, for example, send the links to the pages found via email. The recipient of this email could be another agent. If several agents work together in a system, the system is also called a multi-agent system.

An agent could also be a vacuum cleaning robot or a self-driving car. In this case, the environment would be the physical world.

However, AI has set itself the goal of developing intelligent agents. But what is an intelligent agent? There are two different possibilities here:

- The agent should think and act like a human.

- The agent should think and act rationally, i.e., achieve the optimal result.

Which of the two possibilities is pursued will depend on the area of application of the agent. A personal assistant, such as a virtual secretary, should behave as much as possible like an intelligent human (but of course not imitate their mistakes, such as stubbornness or being in a bad mood on Monday morning). A self-driving car, on the other hand, should not react as sluggishly as a human and should “step” on the brakes as immediately as possible to avoid an accident.

To test the first of these two possibilities, the so-called Turing test was developed [RN10].

The Turing Test

Via Chat

The Turing test was proposed in 1950 by the British “computer scientist” Alan Turing [RN10]. In this test, a test subject chats with a chat app with another person. However, the test subject does not know whether it is a human or an AI and is supposed to find out. There is no contact other than via chat. The Turing test is considered passed if the test subject thinks they were talking to a human, even though it was an AI.

To accomplish this task, the AI must perform the following steps:

- Analysis of natural language in the chat (Language Analysis)

- Extraction and storage of information (Knowledge Representation)

- Logical processing of information (Semantic Processing)

- Memorization of information for later use in the dialog (Machine Learning)

- Determining a logical answer or starting small talk itself (Semantic Processing)

- Formulation of the answer in natural language (Language Generation)

Steps 1, 2, and 6 deal with natural language. In steps 1 and 2, the language is analyzed, and in step 6, it is generated. In steps 3, 4, and 5, work is done with knowledge.

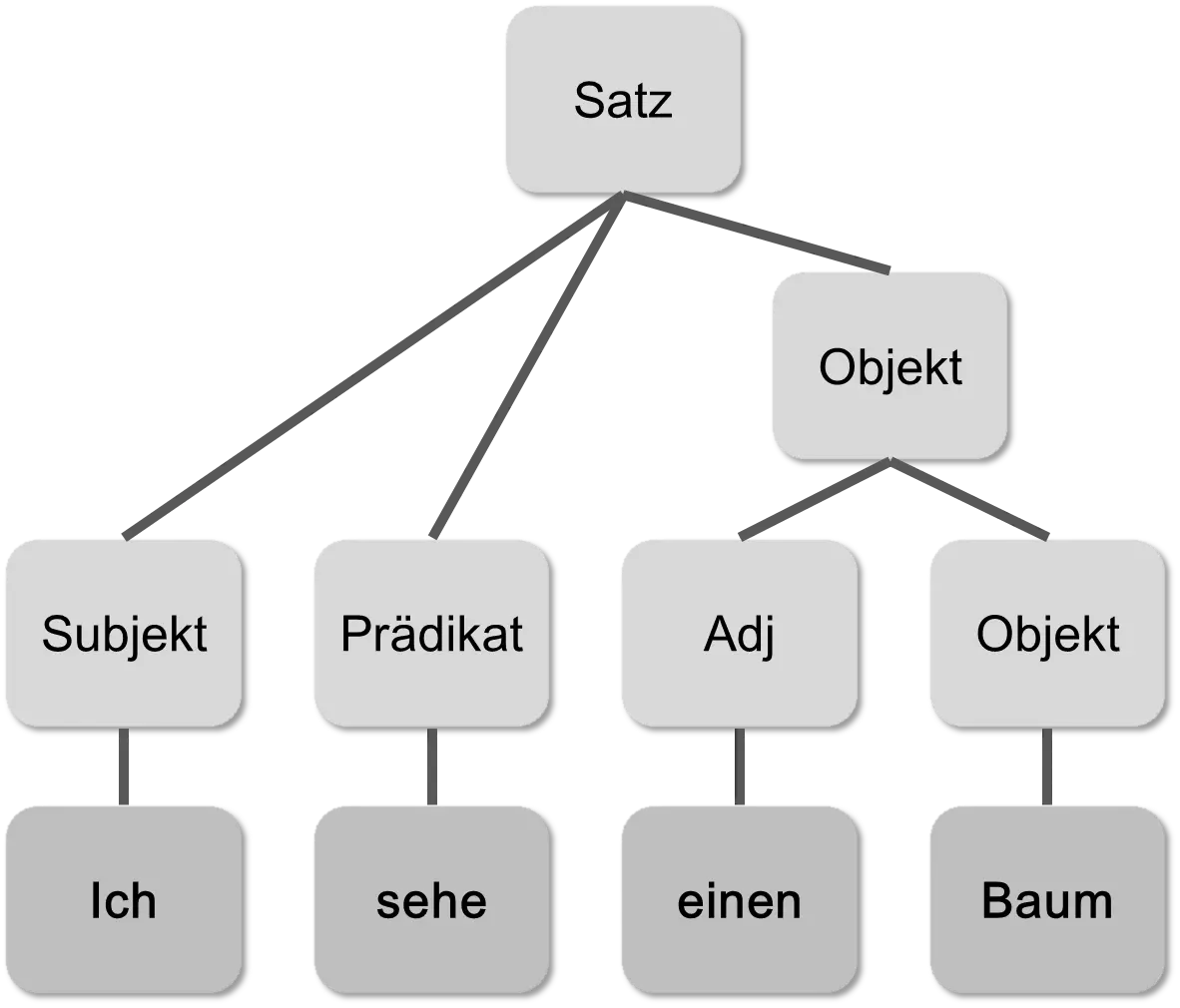

In step 1, a syntactic analysis is performed. Some may have learned it in school. The sentence in natural language is transformed into a tree based on the syntactic categories of the individual words. As an example, in the sentence “Ich sehe einen Baum” (“I see a tree”), it is recognized that the subject “Ich” (“I”) is followed by the predicate “sehe” (“see”), which in turn is followed by the adjective “einen” (“a”) and the object “Baum” (“tree”). The syntactic structure is stored as a tree in the computer.

Such a tree is also called a syntax tree. It is still a relatively easy task to teach a computer the grammar of natural languages. To do this, the computer must have a database of the words and their linguistic information. In addition, it must know the grammar rules, congruences, etc. But here, the amount of information is limited and relatively static. The grammar of a language usually changes only slowly.

It becomes more difficult with the meaning of the words, with semantics. Natural language offers many possibilities for misunderstandings. In a Turing test, one can test whether the AI can correctly resolve pronouns, i.e., whether it understands what “him,” “her,” “its,” etc. refers to. If the test subject says the following sentence:

I see a tree and a bottle of orange juice.

Then ignores the AI’s answer and writes:

I'm thinking about whether I should drink it.

How is the AI supposed to know what “it” refers to? Is it the tree or the orange juice? Humans know that you can’t drink a tree, so “it” refers to the juice. The AI would need to have knowledge about “trees” and about “drinking.” It would need to know something about liquids, that humans can drink liquids, that orange juice is liquid, and that you can’t drink trees. The AI needs semantic information. Such a database with knowledge about the world is also called an ontology. Creating this on a large scale so that an AI has enough knowledge to pass the Turing test has not yet succeeded [RN10]. Semantic processing and the Semantic Web are still subjects of research. In the past, only small progress has been made here. Such ontologies only exist so far for small sub-areas of human life. You can, for example, tell a mobile phone “send a text message to my mother.”

But even if there is progress here, a clever person will be able to trick the AI. They could check the AI for gaps in its semantic knowledge database. The test subject could, for example, also say:

I wonder what kind of one that is.

So, what exactly kind of tree or what kind of orange juice? Humans would argue as follows: Since the test subject has already specified the juice more precisely—it is juice from “oranges”—but not the tree, this sentence probably refers to the tree. The test subject is surely wondering if it is a birch, an oak, or a chestnut. Maybe they don’t know much about biology?

And for that, the computer would already need to have a huge knowledge database and possibly also need a longer time to “think.” Even small children often still have difficulties understanding exactly what the test subject means. To build this analytical ability, humans must learn for many years.

Unfortunately, creating an ontology as a knowledge database is not so easy. It is a very extensive task, and just as with the programming of computers, errors can creep in. This problem will persist as long as computers cannot automatically create such ontologies themselves, and how that is supposed to be possible has not yet been discovered.

Via Spoken Language

A simple extension of the Turing test would be to use spoken language instead of chatting. The test subject can therefore talk to the human or the AI via microphone and speaker. It is no longer difficult to add spoken language. The operation of technical devices with natural language is expected to be widespread by 2020. And programs that you can dictate to already exist today. The problem remains the semantic processing.

The Visual Turing Test and Humanoid Robots

A further extension of the test would be a conversation via video chat. The test subject sees an image of the human or the AI on the monitor.

There are two possibilities here:

- The image is simulated, i.e., generated by computer graphics. The AI only exists virtually.

- The AI is a humanoid robot and is recorded by a camera.

In the first case, the AI would also have to have image analysis (“computer vision”) to interpret the mood of the test subject. The test subject could, as a test of the AI, make a face or perform certain gestures with their arms and hands. Image analyses are nowadays implemented with neural networks, which are treated in section 8.5. The interpretation of human gestures and faces is also possible with neural networks.

In addition, the AI would have to have a face that credibly matches what is said and is classified as “truly human” by the test subject. This will be possible at some point, but not in the next 10 years.

For the second case, however, a human-looking robot is required, and that is currently still impossible and reserved for the films and books of science fiction.

Rational Agents

If an agent is to think and act rationally and achieve the optimal result, a theory of rationality is required. A rational agent is an agent that does the “right thing.” But what is the “right thing” in a certain situation with the means available to the agent? How much time does the agent have to “think”? When solving complicated problems, such as playing chess, it is better to have as much time as possible to try out as many moves as possible “in one’s mind.” For an agent to appear intelligent, it must also consider the consequences of its planned actions. A robot that walks into a wall does not appear intelligent. Rational behavior depends on the environment, the quality of the sensors and actuators, the available time, and the “thinking ability.” The “thinking ability” of a technical agent depends on the number of CPUs, the size of the main memory, and the algorithms used. In section 3.2, we learned about the bounded rationality of humans; a technical agent also has bounded rationality, albeit with different limits.

Rationality is therefore performing the best of possible actions under the given circumstances. For this, one needs a lot of theories from various sciences:

- Decision Theory

- Behavioral Economics

- Logic

- Statistics and Probability Theory

- Mathematics

- Philosophy

- Knowledge Acquisition and Knowledge Processing

- Complexity Theory

- Economics

- Game Theory

- Computer Science and Formal Systems

The task of creating rational agents is therefore a great interdisciplinary challenge. For this reason, it has so far only been possible to create agents for small areas of application, i.e., specialists, such as for playing chess.

In AI, as in complex systems, there is also a difference between the more mathematical methods that process numbers and the “symbolic” methods that also process texts and symbols: The symbolic methods determine data in a form understandable to humans. Here, trees, networks, graphs, and logics, such as predicate logic, are used as knowledge representation languages. Another example is the decision trees discussed in section 7.2. The models of the numerical methods are not understandable to humans and must be used by computer programs. An example of this is the neural networks discussed in the section after next.

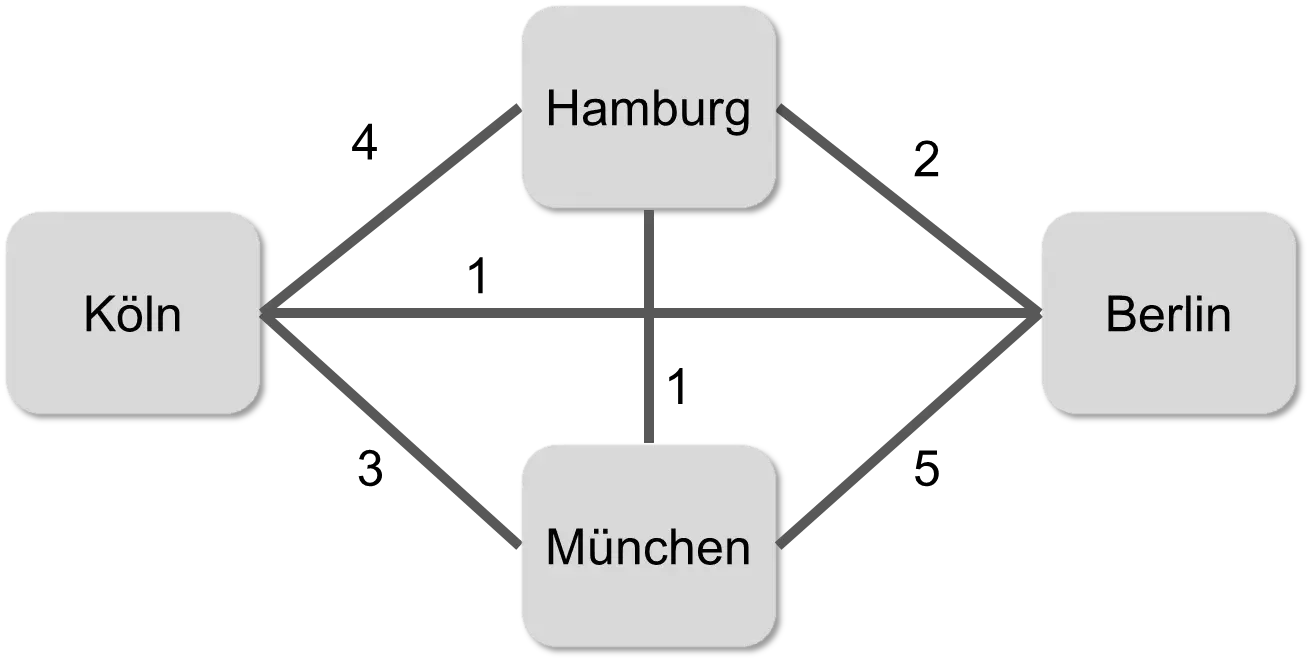

Search

Many problems in Artificial Intelligence resemble the search for a needle in a haystack. Since computers can only do one thing after another, the haystack is searched straw by straw until the needle is found. As an example, let’s consider the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) [CLRS09]. A music band wants to perform in four different cities and plans a round trip in which they want to visit each city exactly once for a concert. The musicians want to perform in Hamburg, Berlin, Munich, and Cologne, collect information about the travel costs, and create the following graph:

Each edge is “weighted” with the cost of the trip. The band wants to start in Hamburg. If they just drive off, e.g., first to Berlin, then Munich, then Cologne, and back to Hamburg, the trip costs 2+5+3+4 = 14.

But which is the cheapest round trip?

The simplest but most time-consuming way to solve the problem is to calculate all possibilities and then choose the cheapest one. With the four cities above, there are three possibilities from Hamburg, then 2, then 1, so a total of 3*2*1 = 6 possibilities. The costs for these 6 possibilities are listed below.

H B M K H: 2+5+3+4 = 14

H B K M H: 2+1+3+1 = 7

H M B K H: 1+5+1+4 = 11

H M K B H: 1+3+1+2 = 7

H K M B H: 4+3+5+2 = 14

H K B M H: 4+1+5+1 = 11

So it can be cheaper than 14, because the optimal trip costs 7 and goes from Hamburg to Berlin, then to Cologne, then Munich and back, or in the reverse order. It therefore made sense to look for the optimal solution.

Theoretical computer scientists have extensively studied the Traveling Salesman Problem. They asked themselves whether one really has to try all possibilities to calculate the cheapest route? Or is there a shortcut? Some problems can also be solved well with heuristics, such as always taking the cheapest local connection.

A major problem in practice is that the number of possibilities grows very strongly with the number of cities. For very many cities, the calculation would take too long even on supercomputers in data centers. Let n be the number of cities. With n cities, the number of possibilities is the so-called factorial of (n-1). That is n-1 * n-2 * n-3 * … * 2. This is a very large number. The Traveling Salesman Problem is a so-called NP-complete problem because the number of necessary calculation steps grows exponentially with n. The haystack during the search becomes very, very large. We will examine this exponential growth in more detail later in another context in section 9.1.

Important: NP-complete problems require an exponential amount of computing time.

This has not yet been proven, but it is very likely1.

In Artificial Intelligence, there are many other “search problems” [RN10], which luckily are not all NP-complete:

- What are the optimal moves in a game of chess?

- What is the optimal path to clean the floor (vacuum cleaning robot)?

- What is the optimal layout for the transistors on a processor?

- Which stocks should one buy or sell today?

- How can a container port be utilized as fully as possible?

- Can a mathematical formula be proven? (automatic theorem provers)

Search can be compared to System 2 of the human brain from behavioral economics. It is the automatic scanning of possibilities. For NP-complete problems, however, the search for a solution can take a very long time.

Neural Networks

In the course of this book, we have already seen various graphs and networks. The human brain is also a network, albeit made of neurons. Mental activity in the brain arises through electrochemical reactions in this network. A neuron can connect with up to 10 to 100,000 other neurons. These connections are dynamic and change when someone learns something new. Biologically, however, this is far more complicated because many other elements, such as axons and synapses, are involved.

The following table contains a rough comparison between a PC from 2015 and the human brain [RN10]2.

| PC 2016 | Human Brain | |

|---|---|---|

| Computing Units | 12 Cores 109 Transistors |

1011 Neurons |

| Storage Units | 1011 Bits RAM 1013 Bits Hard Drive |

1011 Neurons 1014 Synapses |

| Cycle | 10-9 Seconds | 10-3 Seconds |

| Operations / Second | 1010 | 1017 |

| Memory Updates / Second | 1010 | 1014 |

The number of computing and storage units no longer differs significantly between the brain and the PC today. The biggest difference is in the clock cycle: brains are much slower than PCs. A neuron switches a million times slower than a transistor. Overall, however, the brain is much, much more networked and parallel and therefore overall faster. In the PC from the table, only 12 cores work in parallel, while in a brain all neurons can work at the same time. The “architecture” is completely different. Therefore, the PC will not automatically become as intelligent as a brain even if the data in the table converges further in the future. A neuron works quite differently than a transistor. A neuron is biochemical and analog, while a transistor is electronic and digital.

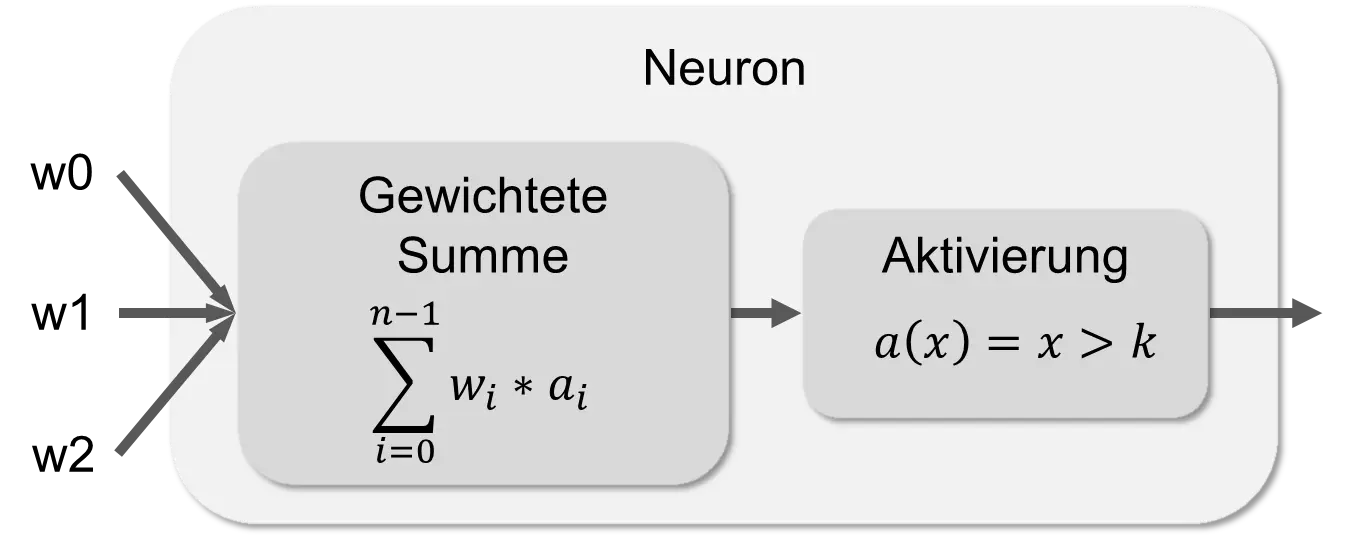

But if the brain is such a good “computer,” then it is obvious to at least imitate it. And that is exactly the idea behind neural networks. Already in 1943, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts created a simple model of a neuron. In the following figure, a simplified neuron is shown.

A neuron has any number of inputs; in this example, there are three: w0, w1, and w2. The edges of the inputs come either from other neurons or from the input of the entire network. Each edge has two pieces of data: an activation level a and a weight w. One also speaks here of “weighted edges”. From the inputs, a weighted sum is calculated in the first component of the neuron. In the second component, the outgoing activation level of the neuron is calculated. In one calculation step, the neuron thus calculates the weighted sum of the activation signals based on the inputs and activates its output signal if the sum is greater than a threshold k.

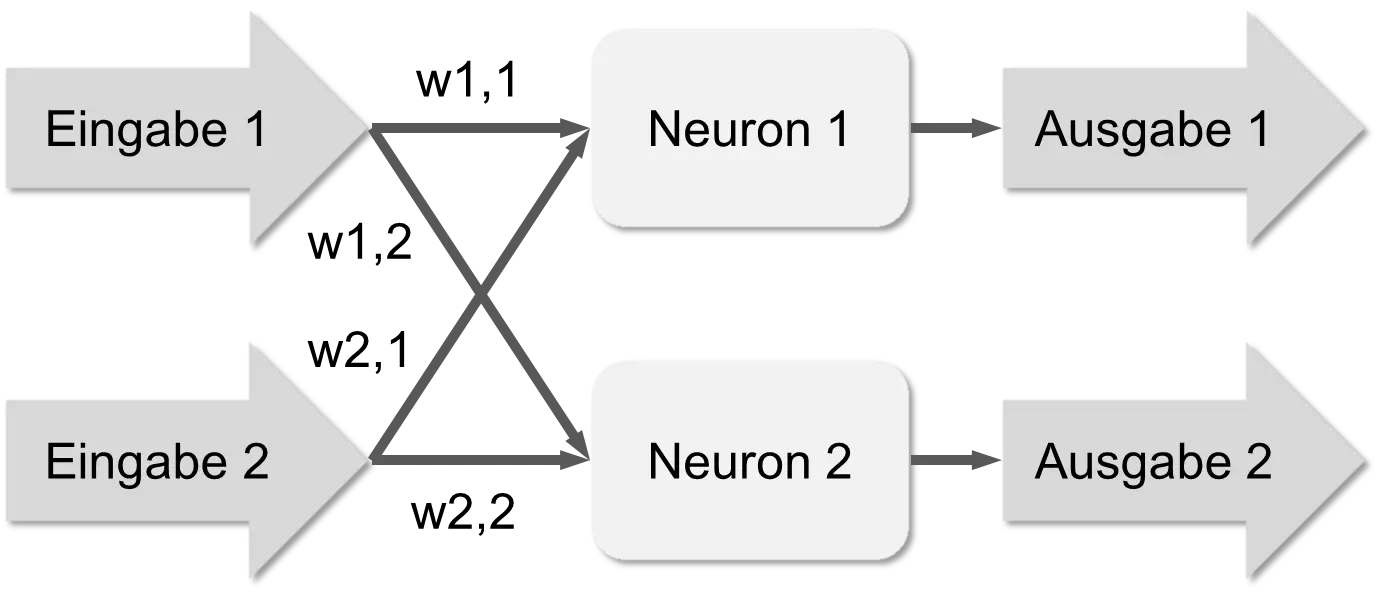

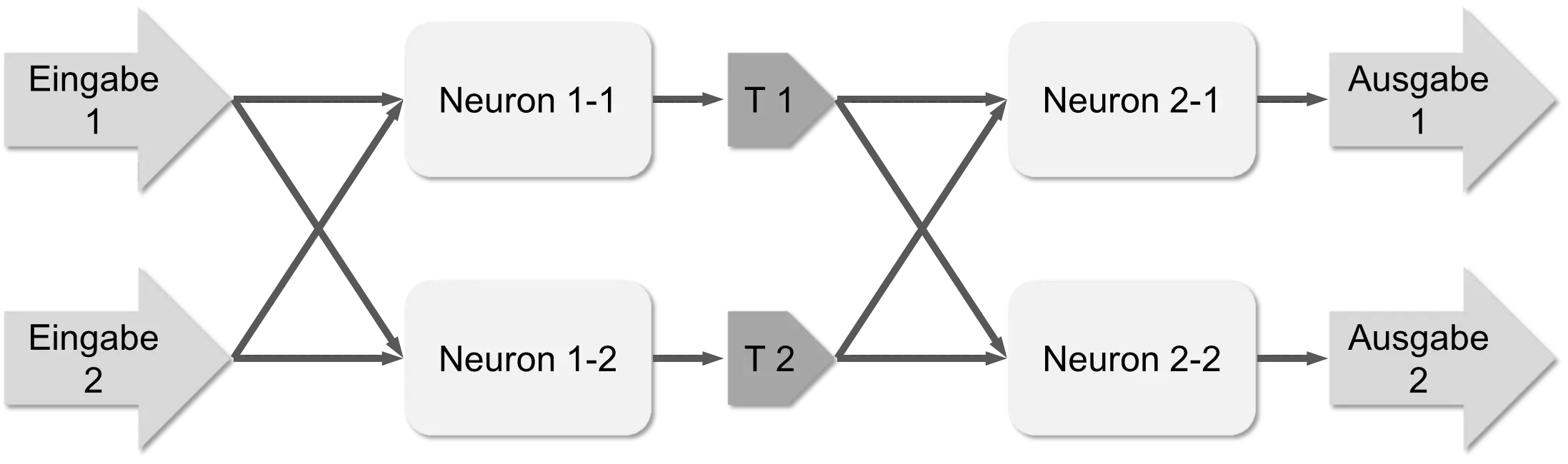

Several such neurons are combined into a neural network. The following figure shows a network with one layer of neurons between input and output.

With such a network, one can represent various functions. You provide two inputs, the neurons calculate their output based on the inputs and weights, and you can read this out at the end. Such a network is already somewhat flexible. If you change the weights, the result of the network changes. Let’s assume the weights have the following values: w1,1=0.4, w1,2=0.2, w2,1=0.6, and w2,2=0.8, and the input 1 (e1) equals 0 and input 2 (e2) equals 1. Then neuron 1 calculates the value w1,1*e1 + w2,1*e2 = 0.4*e1+0.6*e2 = 0.6 and neuron 2 calculates the value w1,2*e1 + w2,2*e2 = 0.2*e1 + 0.8*e2 = 0.8.

One can train such a network. One specifies both an input and an output and calculates what the weights of the edges would have to look like. This corresponds to supervised learning. A network with only one layer, a single-layer network, however, cannot represent many useful functions, as Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert proved in their 1969 article “Perceptrons”. As a result, much research funding in the USA was cut and research on AI was discontinued. It came to the first “AI winter” and neural networks were forgotten.

That changed in the mid-80s when neural networks were rediscovered. With the “backpropagation” algorithm, it had become possible to train multi-layer networks as well. And multi-layer neural networks can learn many more functions, even the non-linear regressions from section 7.2 [RN10]. Neural networks can handle numerical data well; they are “number crunchers.” Often, they can also tolerate noisy inputs or inputs with errors. They are fault-tolerant or robust in the sense of Nassim Taleb (see section 2.7). Therefore, they are particularly suitable for analyzing image data, videos, or voice recordings.

In the following figure, a multi-layer network is shown.

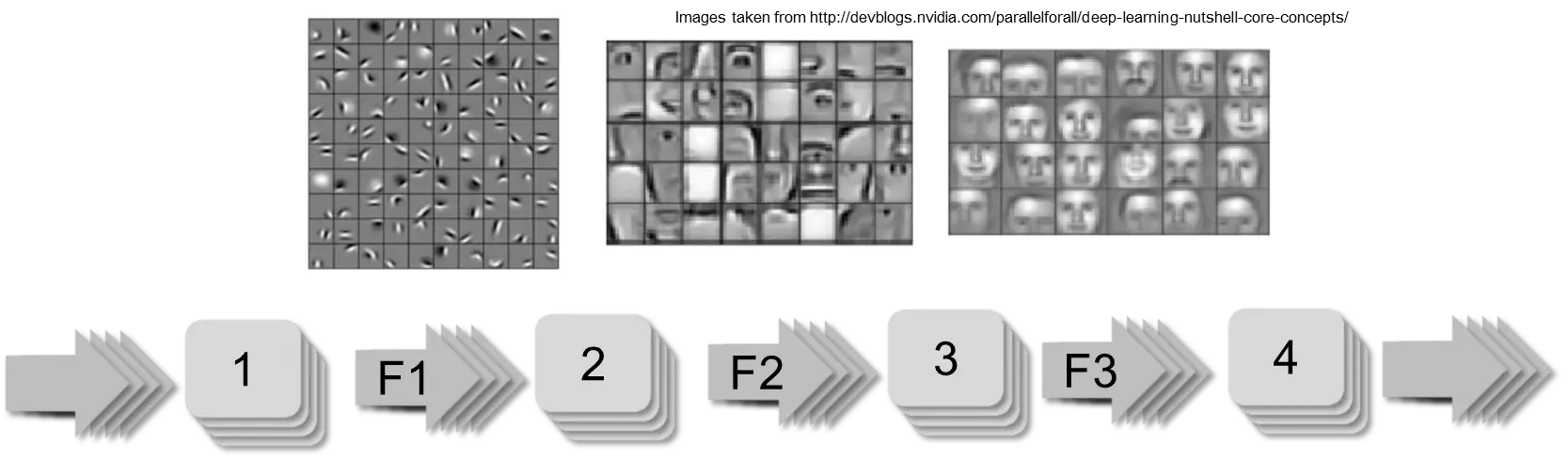

In the middle between the two layers are buffer memories T1 and T2. Real networks of course have much more than just two neurons per layer. Neural networks were regularly used in practice in the 80s and 90s, but they could only be used for simple tasks. Training often still took too long. Therefore, research became quiet around them again at the end of the 90s. That changed again in 2010 when GPU computing made it possible to outsource computationally intensive functions to graphics cards. With a GPU, training a neural network is up to 10 times faster than with a CPU. So from 2010 onwards, larger networks could be trained with more example data. Also, there was now much more data than ten years before. Digital cameras had made great progress. This led to networks with many more layers than before. There were also a number of algorithmic improvements and advances in the theory of machine learning [SB14]. The term “Deep Learning” was introduced for the new techniques. Particularly great progress was made in the area of “computer vision.” An image or a photo can be viewed from different distances. You can get very close or look at larger pieces in context. The trick in deep learning is to introduce a layer for each level of detail. This is shown as an example in the following figure.

The intermediate layers F1, F2, and F3 store “details” (“features”). In reality, there are networks with over 10 layers. These “deep” networks can be arranged in such a way that they enable self-driving cars.

It must be clearly stated here: neural networks learn from example images. One cannot speak of “computer vision” as a “understanding” of an image. After appropriate training, a neural network can with reasonable certainty assign a name to images of already known people or recognize cars on a street. But it is only a mathematical function in a form only to be used for computers [GW08]. The knowledge is “numerically” encoded. Neural networks are not “intelligent” themselves; rather, the intelligence lies in the developers who intelligently arrange the various layers, set the weights and thresholds correctly, and train the network with the right data.

As explained at the beginning of this section, neural networks are a simplified replica of the brain. The biggest difference from a real brain, however, is that a computer is based on transistors made of silicon that have a 0/1 logic. A brain is biochemical and analog, so it can represent many different intermediate states. We will go into this later in section 10.6 regarding the Singularity.

These neural networks are comparable to System 1 from behavioral economics. They can be used to store heuristics and “fuzzy” logic.

Intelligent Robots

For a human, it is very easy to move through an apartment but hard to play chess very well. For a robot, it is exactly the other way around. Abstract thinking, which is exhausting for humans, is easier to automate than sensorimotor movements, which are easy for humans. This contradiction is also called Moravec’s paradox, after the robot researcher Hans Moravec [BA14, RN10].

To speak with Systems 1 and 2 from section 3.2: System 1 was previously difficult to automate, System 2 was easier. The situation has improved a little due to “Deep Learning.” But even today, there is still no robot that can completely clean an apartment without breaking too much. Because it was very hard to teach a robot a sense of balance. For this, it needs good sensors that tell it what its environment is like, but also what state its joints are currently in. This must be calculated in real-time and corrected as quickly as possible if there is a risk of imbalance. Recently, however, progress has been made here, and it looks today as if the “balance problem” will be solved in the near future.

Another task of a robot is to find its way in unknown environments. For this purpose, the robot creates a map of its surroundings. However, a robot can only “understand” its surroundings with functioning image recognition. But as mentioned, image recognition was not practical enough before “Deep Learning.” The robot must enter the objects it has recognized on its “inner” map. At the same time, it must determine its own position on the map. This is harder than it looks at first glance. A robot moves with motors. It can tell its motors: move me 1 cm forward. But whether it has then really covered 1 cm distance or only 0.95 cm is decided by the resistance of the floor. On a parquet floor, it goes much “smoother” than on a thick carpet. Where it is located exactly afterwards, the robot must check visually. In English, the problem is called “Simultaneous localization and mapping” (SLAM). In the meantime, the right algorithms have been developed for this. SLAM was still considered a major challenge for robotics in 2008, but has since been solved satisfactorily for many areas of application [BA14].

Today, robots are used in many areas. Mainly in industry, e.g., in the production of automobiles or in warehousing. Robots have also moved into private households as vacuum cleaning robots. The city of Tokyo plans to use self-driving taxis at the 2020 Olympic Games. The robots are therefore continuing their advance. Later in section 11.7, the consequences for the labor market will be discussed.

Status of AI

In the 1960s, many AI researchers predicted the imminent appearance of intelligent computers. AI is a beautiful example of the “horizon problem” in research projects. At first, everything looks very simple; you make a plan and think you should be finished in five years. During the work on the project, however, new questions arise that you hadn’t thought of before, which were possibly even unknown before. The “knowledge horizon” shifts during the project. The original plan is obsolete. On the way, however, interesting things have been found out. It was very important to deal intensively with AI, because otherwise many products would not exist today, such as vacuum cleaning robots and chess computers. But it must also be clearly stated that AI has not reached its end goal of “intelligent agents.” And it currently does not look like there will be universally intelligent agents in the near future (until 2025). Because in Artificial Intelligence today there are the following limitations:

- AIs do not have general universal intelligence; they are specialists and are only used in small, defined areas

- AIs cannot “understand” information

- AIs are not “creative”

- AIs have no introspection, cannot “understand” themselves

- AIs have no consciousness and no self-knowledge

Today’s AIs at most “appear” intelligent, but they are not.

General AI

So far, AIs have only been developed for special areas of application and tailored to one task. A person is only “intelligent,” however, if they are flexible and can learn new things. Nowadays, the creation of a universal AI is not possible in practice.

Semantics

This is partly due to the fact that computers today cannot perform semantic processing of information. What does the word “Hamburger” mean? It can be a food item or a person. Humans infer this information from the context. These semantic analyses, however, are very complicated. No method has yet been discovered with which one could simply extract semantic knowledge from the internet. And to have this knowledge manually encoded by experts is very labor-intensive. But here, of course, progress will be made over time. For example, a “knowledge database” is conceivable that one can ask logical and statistical questions. But progress in this area is slow and will not proceed by leaps and bounds. The bottleneck is the creation of large knowledge databases and ontologies. And for this, human mental work is currently still necessary.

Consciousness

Can one be intelligent at all without having a “consciousness”? Consciousness is not so easy to define; it roughly means being “aware” of oneself and one’s “existence” [Bla05]. Famous here is the saying “cogito ergo sum” by René Descartes. There are researchers who claim that consciousness is the emergent result of the complex system of the brain [RN10]. But there are also researchers who say we don’t even know exactly what “consciousness” itself actually is [Bla05]. For example, no specific area for consciousness has been found in the brain. And as long as humanity does not know how something works in nature, it cannot replicate it. So the current findings are not yet far enough to be able to answer the question of whether computers can have a consciousness. Scientists differ in their opinions on this, however [Bro15].

Imitation of Humans

There is a very big difference between AI and humans: AI has no animal heritage. For humans are intelligent mammals descended from apes. In addition to intelligence, humans also possess instincts inherited from animals, such as sexuality. The zoologist and behavioral researcher Frans de Waal found out in chimpanzees that they have a pronounced social behavior and also help each other with delousing [Waa07]. So they already know reciprocity and win-win situations. But when it comes to food and sex, male chimpanzees try to dominate the other males. To do this, in addition to physical violence, they also use threats, bluffs, and other tricks. According to de Waal, it seems as if chimpanzees intuitively know many passages from Niccolò Machiavelli’s book “The Prince”. Humans also have these “instincts.” As children, humans must first learn to resolve conflicts peacefully, to reconcile with each other after an argument, etc. An AI, on the other hand, will not have this “animal heritage.” The AI will feel no urge to reproduce and dominate others. An AI is only information processing and conclusions, but not the mammal. For this reason, many predictions about AIs that suddenly develop self-awareness and threaten the world are nonsense, because an AI does not have this “animal” drive for dominance. In the feature film “Blade Runner” from 1982, very human-looking robots suddenly develop a consciousness and want to extend their lives, so they have a “survival instinct.” But exactly this “instinct” would first have to be programmed into the AI, because it will not arise by itself [Bro15].

Outlook

One can compare Artificial Intelligence with the development of means of transport. By nature, humans can walk. Some are a bit slow at it, others are already faster. The results in sporting competitions in the 100-meter run have gotten better and better. In terms of means of transport, there has already been significant progress: there are bicycles, mopeds, motorcycles, cars, trains, and planes. Humans can now move much faster with the help of technology.

The artificial intelligences developed so far correspond more to bicycles. A car would correspond to an AI that could pass the Turing test. An AI can “fly” when AIs are as intelligent as humans and have self-awareness. But even to the car, it is still a long way, and many inventions have yet to be made beforehand.

Until then, however, Artificial Intelligence will definitely have strong effects on progress and the working world. It is expected to change many professions, enable new professions, and also make some professions superfluous. We will deal with this later in section 11.7. If, however, it should be possible in the long term to produce truly “artificial intelligences” that are at least as intelligent as humans, then it could lead to the so-called “Singularity,” which is discussed in section 10.6.

Interested readers who would like to get to know different points of view on the topic of AI are referred to the book “What to Think About Machines That Think”, edited by John Brockman [Bro15].

-

This is the famous open problem of theoretical computer science P = NP or P ≠ NP. P ≠ NP is very likely and it is also very likely that this cannot be proven. ↩

-

X^Y is the mathematical notation for X to the power of Y. It is 10^1 = 10, 10^2 = 100, 10^3 = 1000, etc. If Y is negative, then X^(-Y) = 1/(X^Y) applies. So 10^(-1) = 1/10, 10^(-2) = 1/100, etc. ↩