Notice

This page was semi-automatically translated from german to english using Gemini 3, Claude and Cursor in 2025.

Systems and Networks

What are Systems?

The word “system” comes from the Greek and means “a whole composed of several individual parts”. These individual parts are related to one another and “work” together. An individual part can itself be a system, which is then called a subsystem. The word “system” is frequently used in everyday life, such as in solar system, ecosystem, and computer system. Most of the time, “systems” are distinguished by their field of application: technical, social, economic, biological, and ecological systems.

Systems can be natural or artificial, i.e., created by nature or by humans. Natural systems are the subject of the natural sciences. Here, models of nature are created and theories about behavior are established. These theories are tested using experiments. Due to the high “complexity” of nature, scientists have made their work easier by dividing nature into the subsystems of physics, chemistry, and biology.

However, artificial systems are not studied by “art sciences” or “artificial sciences,” but by a variety of different disciplines [Sim96]. This has historical reasons and has led to the field of artificial systems being difficult to grasp as a whole.

Certain facts can be explained better if a simplified model of reality is used. The model is an abstraction. In the natural sciences, it is often not necessary to go back to atoms in every last detail. Physics, for example, can precisely predict the movements of planets even with an abstract model. To make a prediction about planetary orbits, one can reduce the observed variables to the masses of the planets, their circumferences, the gravitational constant, etc.

This principle is called “reductionism” today, and one of its first advocates was René Descartes (1596 - 1650). The idea was that one breaks a complex system down into its individual parts, analyzes them individually, and reassembles the system afterward. Progress and industrialization only became possible through this method [Mit09].

At the beginning of the 20th century, however, the first doubts arose. Many facts could not be correctly explained this way: the weather, living organisms, epidemics, the economy, or the spread of cultural developments—in short, everything dynamic or living. This is often summarized with the saying “The whole is more than the sum of its parts.” Such systems are called “complex systems,” such as the following:

- Insect colonies of ants or bees

- The blood circulation in the human body

- The economy and the financial system

- The development of cities and metropolitan areas

The theory of complex systems has been developed since the 1980s [Mit09, Hol14, EA96, Bat07]. It emerged in various fields such as computer science, neuroscience, biology, economics, cognitive science, and artificial intelligence.

Correlation and Causality

When analyzing systems, one must be careful not to confuse correlation and causality. These terms sound complicated but are quite easy to understand.

Let’s assume a young alien student has some free time, flies to Earth for the first time, and looks at the faces in a pedestrian zone of any city in Europe. He notices two differences among the people: some have long hair and some have short hair. Furthermore, some people have red-painted lips and others do not. “How does that happen?” thinks the alien and creates a model with these two observed variables: “Long Hair” and “Red Lips.” After observing 20 people, he creates the following table with his measurements:

| Long Hair | Red Lips |

|---|---|

| YES | YES |

| YES | YES |

| YES | YES |

| YES | YES |

| YES | YES |

| YES | YES |

| YES | YES |

| NO | YES |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| YES | NO |

| YES | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

| NO | NO |

The alien tries to recognize a connection between the two variables and sees that very often the same value is present in both columns. In 17 out of 20 rows, the same value “YES” or “NO” appears in both columns. Statisticians call the simultaneous occurrence of values “correlation.” The correlation of two variables indicates how strongly two variables depend on each other. If they always have the same values, then the correlation is high. Correlation can take values from -1 to 1. The alien calculates a correlation of 0.698. That is not yet very high, but it suggests a connection.

“But how are the two variables related?” the alien asks himself: “Do the red lips cause the hair growth?” or “Does long hair lead to red lips?” If these two variables are related, what is the cause, and what is the effect? How are the two variables “causally” related?

The alien has observed a correlation between two variables, but that does not mean that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the two. It is not the case that red lips are created by long hair or vice versa. This is a statistical fallacy. A cause-and-effect relationship is also called a causal relationship. Correlation does not equal causality.

And the secret for the alien student is that there is another unobserved variable that he did not observe: gender. Because he did not include this variable in the model and confused correlation with causality, he researched complete nonsense.

Therefore, it is important in data analysis that there are as few unobserved variables as possible. For companies today, this leads to them first collecting a lot of data within the framework of data warehousing and Big Data without knowing what they can actually do with it. It could be data about a variable that will become useful later. Later in the book, we will cover these topics and data analysis with Data Science in more detail. On the other hand, many observable variables are often not important. A physicist observes different things than a chemist. For practical reasons, the amount of observed variables is therefore restricted. The model represents only an excerpt; it is an abstraction. The alien in the example above could also have measured the outside temperature and humidity. But these are not relevant to his question. Which variables are used depends on what the model is needed for. The principle of Ockham’s Razor (named after William of Ockham (1288 - 1347)) states that of two models explaining the same fact, the simpler one should be chosen.

Important: The model should be as simple as possible, but not reductionist.

Models, Graphs, and Networks

A “Simple” Model

This is the only chapter in which program texts with mathematical formulas are shown. It is not necessary to understand the code for further understanding of the book. However, readers without programming experience will get a first impression of programming.

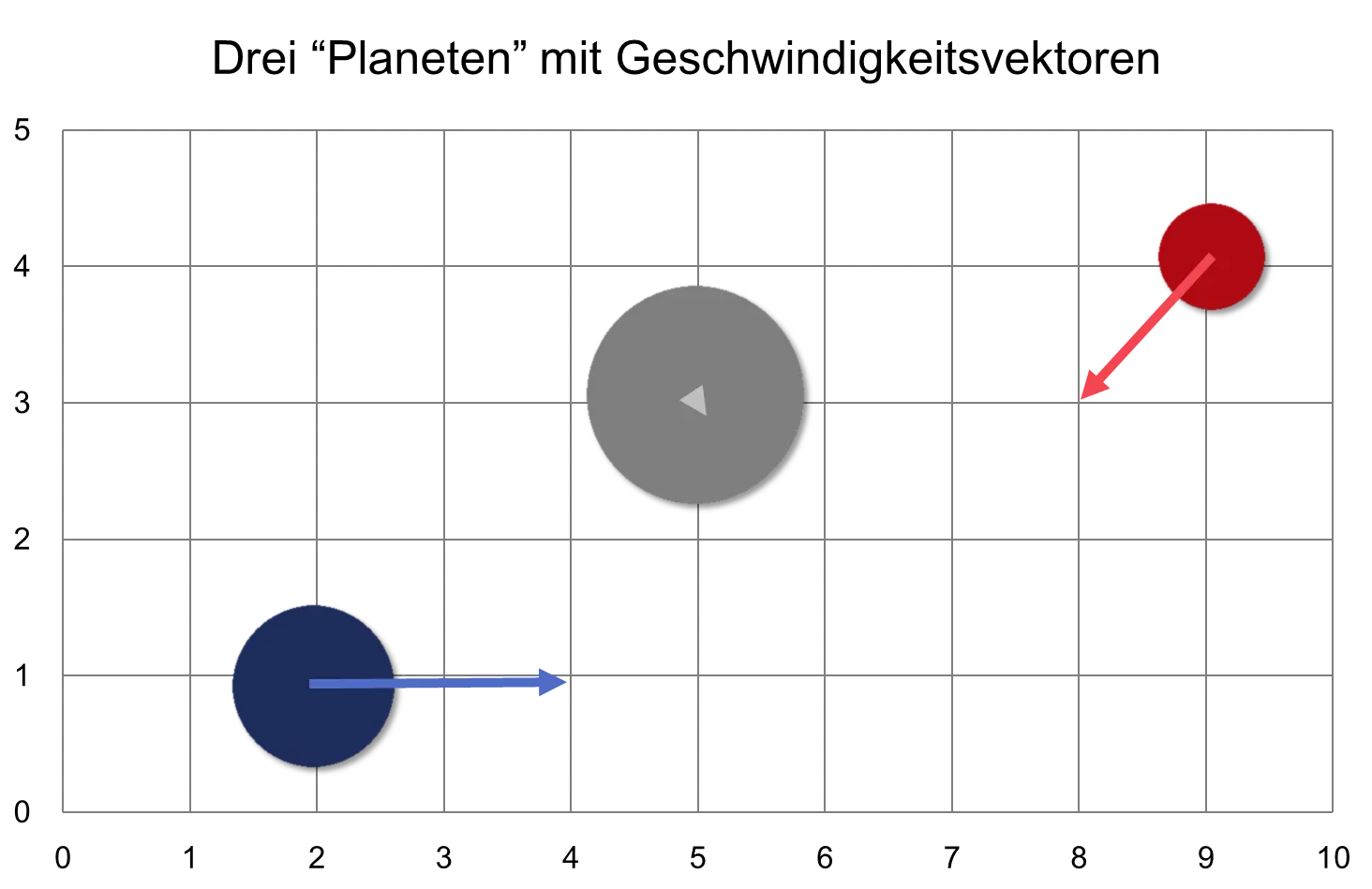

We start with a very simple system: in a distant two-dimensional galaxy, there are three planets: a small red one, a medium blue one, and a large gray one. We want to simulate the movements of these planets. In the following figure, these “planets” are seen with different colors and sizes on a coordinate system:

The coordinate system has a horizontal x-axis with values from 0 to 10 and a vertical y-axis with values from 0 to 5. A coordinate is given as a pair of numbers (x, y). The blue planet, for example, is located at the coordinates (2, 1).

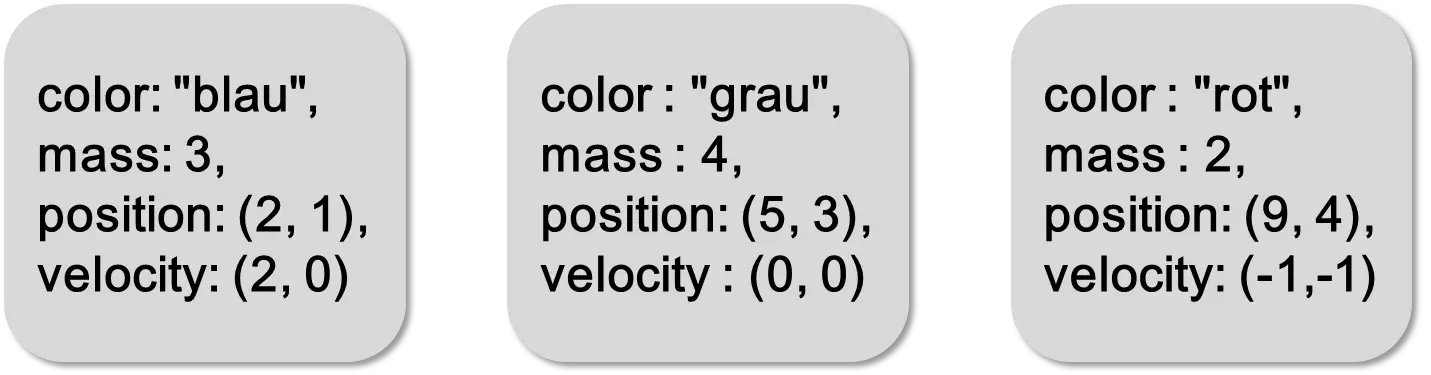

In computer science, object-oriented programming has become established. For each planet, we need the following attributes, which together define the “state” of the object:

- a color “color”

- a mass or weight “mass”

- a position “position” in space in 2D coordinates (x, y)

- a direction-and-velocity vector “velocity” in 2D coordinates (x, y)

The direction-and-velocity vector expresses the movement of the planet. The velocity is expressed by the length of the vector. Such a vector is often represented in diagrams with an arrow.

In software development, English variable names are used in most projects. This is due on the one hand to international projects and employees who do not speak German, or to English literature. Only a small fraction of English computer science literature is translated into German. Therefore, you cannot study computer science without knowledge of English. So, English names are also used here.

The following program code represents the definition of the class Circle. It is a direct implementation of the list above.

class Circle {

String color;

num mass;

Vector position;

Vector velocity;

…

}

The program is in the programming language Dart1. It states that there is a class called Circle that has as attributes a character string (String) named “color”, a number (num) named “mass”, a vector named “position”, and a vector named “velocity”.

One can create so-called “objects” from this class. This is done here with the function new. In the following example, the three planets are created.

var u, v, w;

u = new Circle(color: "blue", mass: 3, position: new Vector(2, 1), velocity: new Vector(2, 0));

v = new Circle(color: "gray", mass: 4, position: new Vector(5, 3), velocity: new Vector(0, 0));

w = new Circle(color: "red", mass: 2, position: new Vector(9, 4), velocity: new Vector(-1, -1));

For the program, these circles have the names u, v, and w. One could also use more descriptive names, but they should be short here.

So far, the Circle class only has attributes for storing its data. But a class can also have so-called methods with which it can change the values of its own attributes. We want to calculate the new position from the old position and the velocity by adding the velocity to the current position. To do this, we must give the Circle class a method that we call step():

class Circle {

… as before …

step() {

position = position + velocity;

}

}

A method is recognized by the parameter list “()” and the curly braces “{}”. With step(), velocity is added to the position. Before calling step(), the blue sphere has the following state:

color: blue, mass: 3, position: (2, 1), velocity: (2, 0)

And after a single call, position = (2+2, 1+0)

color: blue, mass: 3, position: (4, 1), velocity: (2, 0)

And after another call:

color: blue, mass: 3, position: (6, 1), velocity: (2, 0)

Here it should also be noted that the old values are lost. The Circle does not remember its history; it has no memory. This would have to be programmed in extra. That is not so difficult, but it is associated with effort and labor time. For this reason, programs are always as minimal as possible, i.e., they should contain just enough code so that they can fulfill their task. If this were not just a simple, unimportant circle, but the contents of a bank vault, then one should remember the previous state. In real computer systems, important data is stored in databases and the methods are logged in so-called logging files so that one can later check who changed what and when.

Important: Programming is tedious because everything must be specified exactly. Tediousness costs labor time and thus money. That is why in computer science, one tries to design programs to be as simple as possible and as extensive as necessary.

The step() method changes the state of the object, so it is also called a state change method. Mathematically speaking, the method expresses the difference between the two states; it is a difference function.

We have programmed a model of the three spheres and can “simulate” this by calling the step() methods for all three circles u, v, and w:

num t = 0;

while (t < 10) {

u.step(); v.step(); w.step();

t = t + 1;

}

If you want to understand this program code, you have to “interpret” it line by line. The variable t stands for time and initially has the value 0. The value of this variable can be changed again later. Then, in a so-called while loop, the step() methods of u, v, and w are called and then t is increased by 1. The variable t is incremented step by step starting from 0. At the beginning, we are at time t=0, then comes t=1, then t=2, etc. The while loop ends when t equals 10.

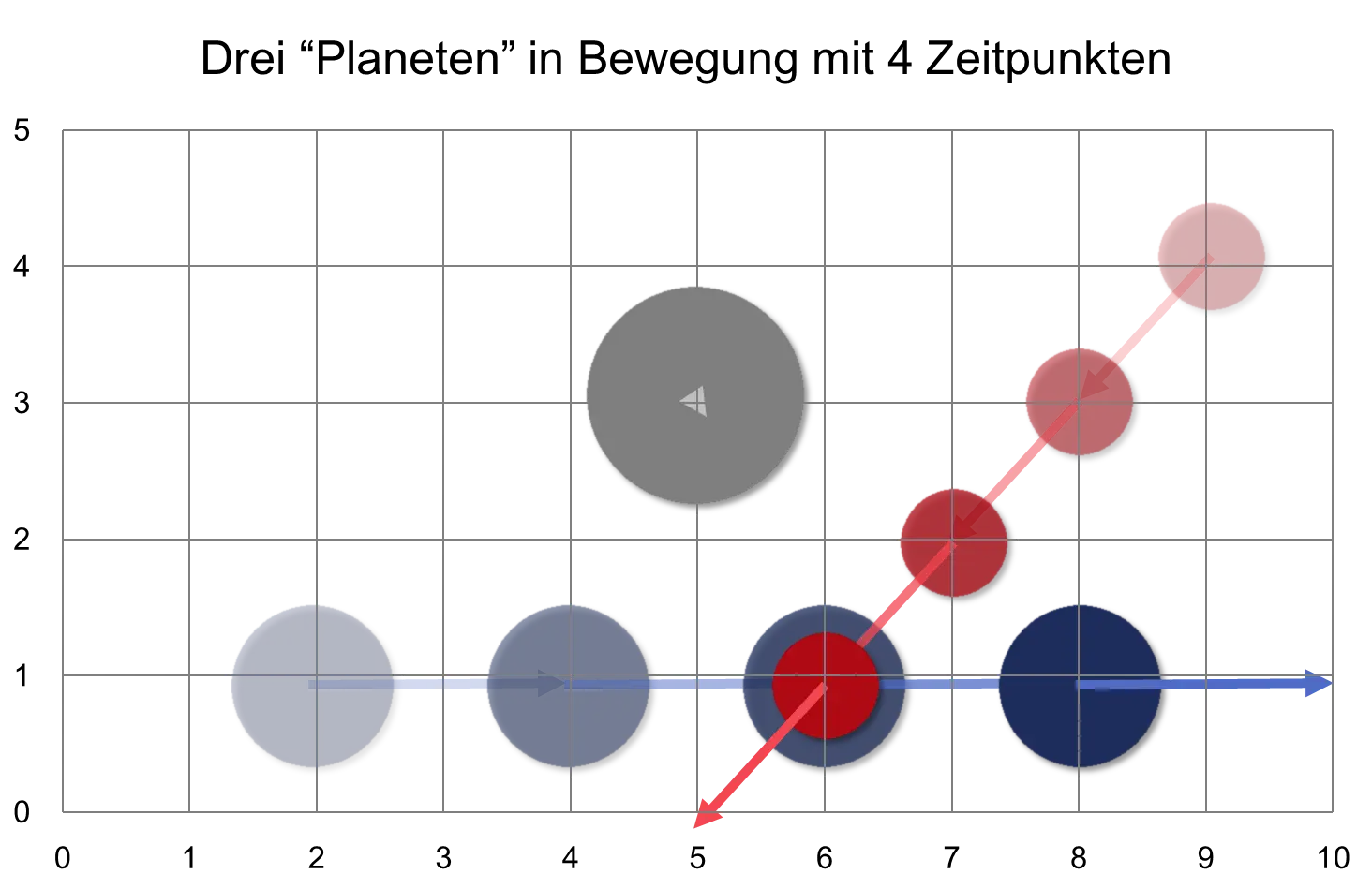

We have thus written a simulation. In the following figure, the changes for the first three steps are plotted:

The velocity of the gray sphere is (0, 0), so it does not move. The medium-sized blue sphere moves in the direction of the x-axis because the velocity is (2, 0), and the small red sphere moves diagonally “down left” because the velocity is equal to (-1, -1).

Now our time in variable t has a big difference compared to real time: natural time is continuous and does not consist of “steps.” A second can be broken down into smaller parts as many times as you like. But the simulated time t is discrete; it consists of individual points. This is a significant simplification, but it makes programming the model easier.

One could now ask the question whether the red and blue circles will collide? In reality, yes, but not in this model. One would first have to program “collision detection.” The model does not reflect reality.

Differential Calculus

A problem with our model is that we have to do a lot of calculation to find out where the spheres are at time t=1,000,000. In the simulation above, we start at t=0 and then have to call step() a million times. This can be quite demanding for the computer with extensive models. Is there a faster way?

In mathematics, differential calculus has established itself here. With this, one can determine a so-called closed formula for a difference function, with which the result for any value of t can be calculated directly. For the three circles, this is simple, for example. The following three functions calculate the position of the sphere at time t even without a simulation:

red(t) = (9, 4) + t * (-1,-1)

blue(t) = (2, 1) + t * (2, 0)

gray(t) = (5, 3)

Important: With a closed formula, the values for any point in time t can be calculated very easily. The simulation is not needed.

In many cases with elaborate models, this is a huge time saver. But unfortunately, these closed formulas only exist for fairly simple difference functions or step() methods. We will come back to this later.

A “Complicated” Model

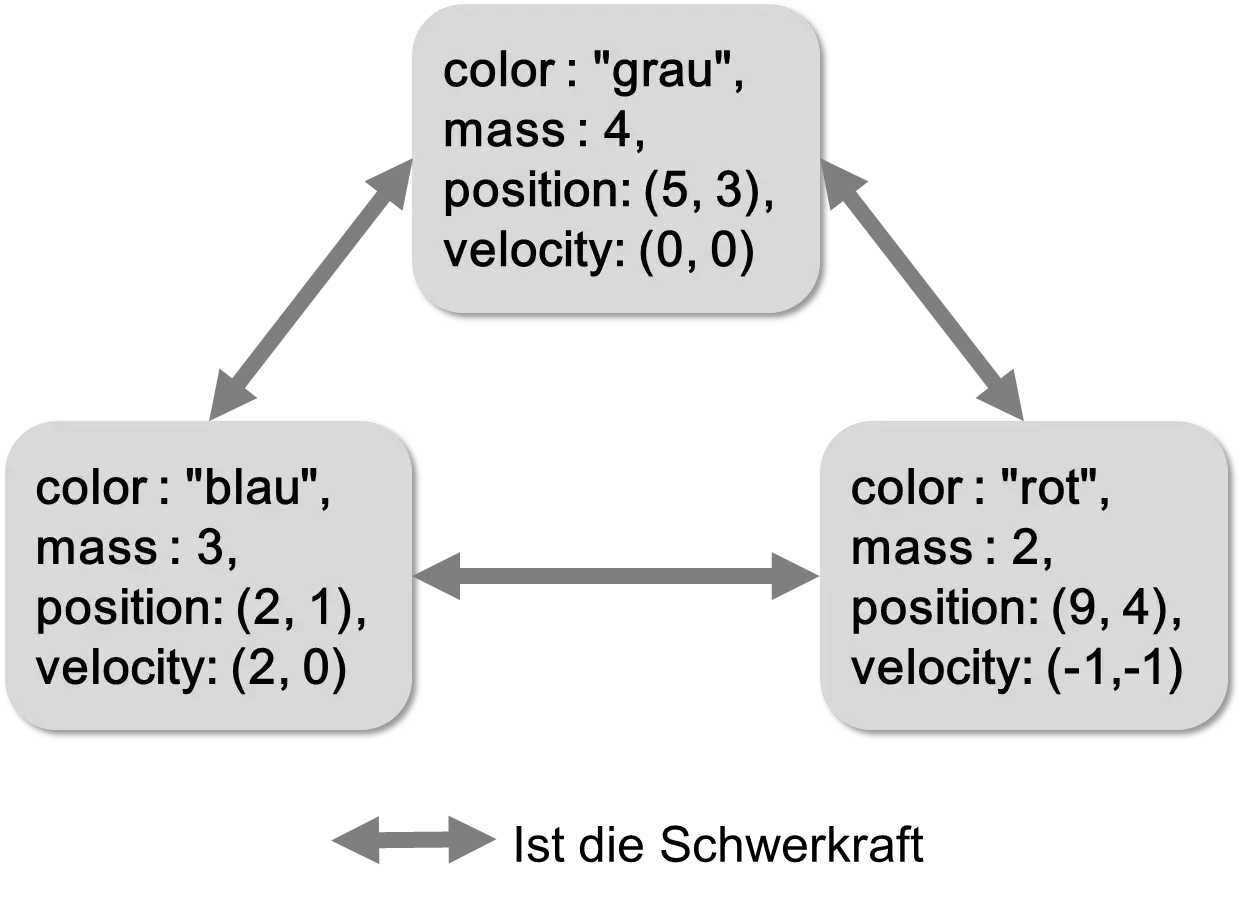

In the distant galaxy of the three circles, researchers make a new discovery: gravity. Gravity is proportional to the mass of the planet and the distance and ensures that the other planets are attracted. The planets influence each other. We skip the physical theory here and adapt an existing program to our two-dimensional model [Wil13].

The step() method with gravity is, however, a bit more complicated. Readers who are not interested in programming can rest easy, as it is the last code in this book. Interested readers, on the other hand, can try out and download the code on the book’s website:

step() {

Vector force = new Vector(0, 0);

objects

.where( (Circle c) => c != this)

.forEach( (Circle c) => force += bodyBodyInteraction(position, c.position, c.mass));

velocity = velocity + new Vector(force.x / mass, force.y / mass);

position = position + velocity;

}

In the first simpler step() method, only the position was changed. With gravity, however, the velocity also changes. First, the forces force for all other circles in objects are added with the auxiliary function bodyBodyInteraction(). Then a new velocity is calculated and with it the new position.

The simulation has thus become more complicated. The movements of one planet depend on the other planets. This simulation is the basis of the so-called n-body problem, which has many scientific applications [Wil13]:

- Simulation of planetary orbits in astronomy

- Molecular modeling of chemical molecules

- Particle systems in the simulation of water or fire

Graphs and Networks

The previous presentation was the illustrative one from the “real” physical world. But we can also represent the model more abstractly. In our first system, we have three elements between which no dependencies exist. We simply draw them side by side in the following diagram.

Each element has several attribute-value pairs that determine the properties or state. The individual elements are independent of each other. In the second system, gravity acted on the “planets.” In the following figure, gravity is drawn as an arrow:

We can also draw the model a bit more abstractly and add “elements.”

Such an abstract structure is called a graph or a network. Graphs are used in many sciences, such as mathematics, computer science, social sciences, economics, and biology. Even the public transport plans of a city or the route map of a railway are graphs.

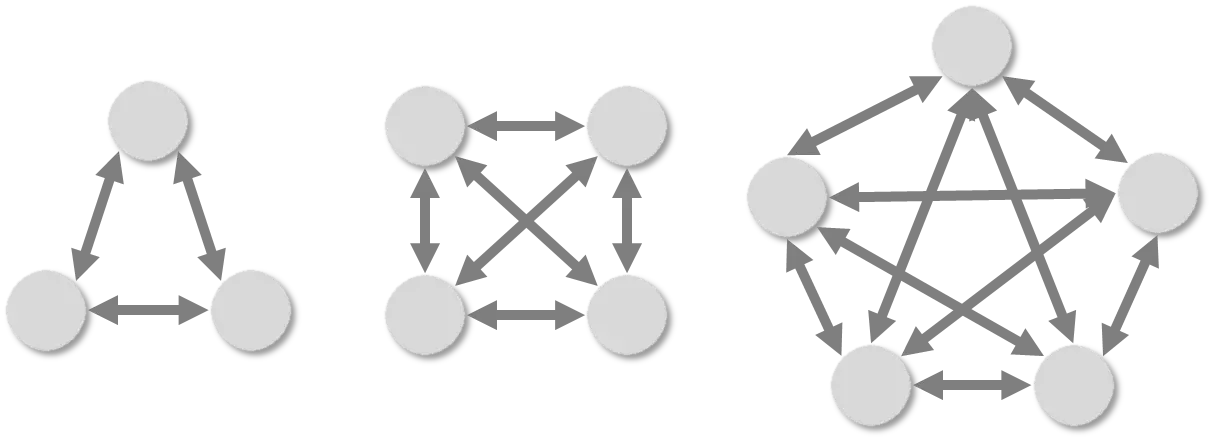

A graph consists of a set of nodes (the “planets” in our simulation) and edges between these nodes, which are represented by the black arrows. The edges model relationships, also called relations, between the nodes. Gravity was the relationship between the individual “planets.” The last diagram, for example, contains three graphs: the left graph has 3 nodes and 3 edges, the middle one has 4 nodes and 6 edges, and the right one has 5 nodes and 10 edges.

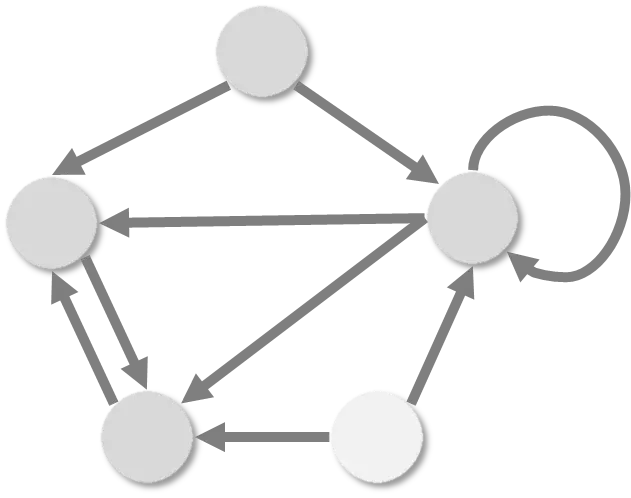

There are different types of graphs. In the following example, the edges are “directed” and no longer bidirectional, and “loops” are allowed, with which a node can be connected to itself.

With directed graphs, it can happen that some nodes can no longer be reached by others. The light node, for example, only has “outgoing” edges; the others cannot reach it.

The advantage of the high degree of abstraction of graphs is that they can be used in different fields and the graph theory can be “reused.” For example, there are the following networks that can be well modeled and analyzed with graphs:

- Technical networks: Internet, telephone network, electricity, water, gas

- Social networks: Friendships, families, acquaintances, contacts

- Economic networks: Spread of financial crises, logistics, transport

- Information networks: News, Internet, WWW

- Biological networks: Metabolic networks, transmission of epidemics, neural networks

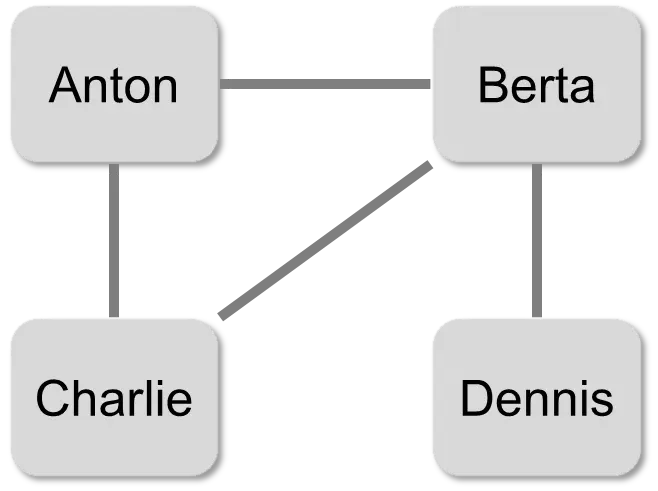

In a social network, people are friends with each other. In the following diagram, a network with the four people Anton, Berta, Charlie, and Dennis is represented.

With bidirectional edges, the arrowheads are usually omitted, as in this graph. If two nodes are connected, then they are friends. The number of edges of a node is then the number of friends of the person in the network. Anton has two friends and Berta has three.

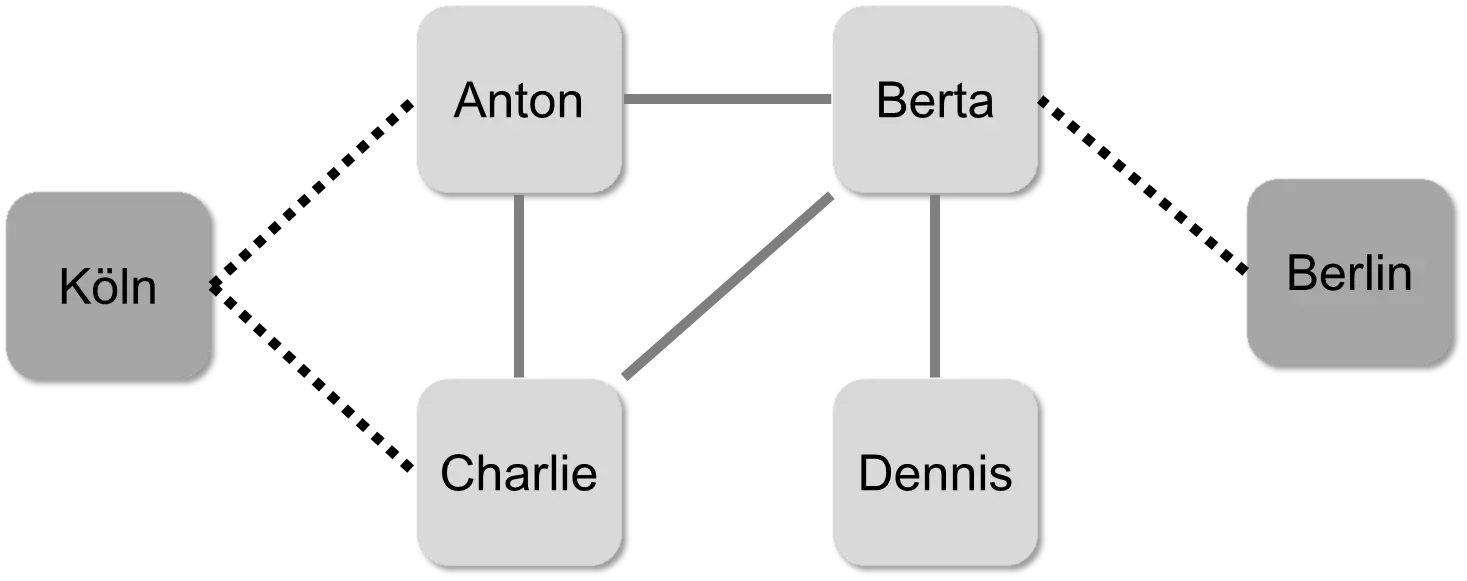

A network can also consist of nodes of different types. In addition to people, it could also include cities, for example. These different types can be visualized, for example, by different shapes or colors. In the following example, the cities are marked with darker nodes. The edges to these nodes are drawn with dots.

Anton and Charlie live in Cologne, Berta in Berlin, and Dennis’s place of residence is unknown.

In reality, graphs can become very complicated. Programs for visualization have been developed here, such as Gephi2.

The analysis of networks is still a fairly young field, because without computers, only very small networks can be analyzed. In the future, a large part of science will use network theory or graph theory.

Computer Networks

Computer networks can also be represented as graphs. The following different types of networks are the best known:

- Internet: Large international network, mostly connected via cable

- Intranet: Network connected via cable in companies or other organizations

- WLAN (“wireless local area network”): Network for smaller buildings, home network for private households

- 3G and 4G: Telecommunications networks for mobile phones

There are two main methods of how different devices can be connected to each other:

- Client-Server

- Peer-to-Peer (P2P)

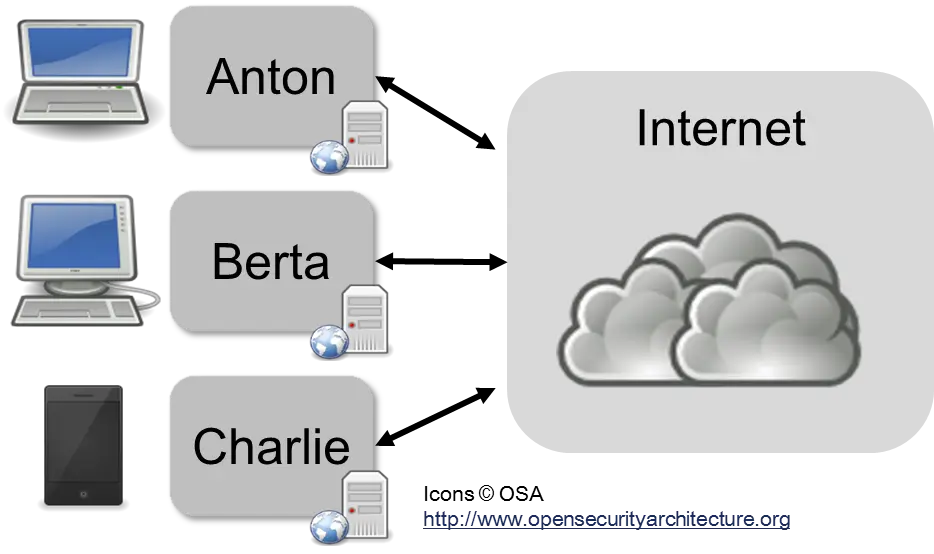

As an example, let’s assume Anton, Berta, and Charlie want to log in to a website where they can “chat” with each other. The computer for this website is called the “server.” Anton, Berta, and Charlie use a web browser as a “client.” This architecture is therefore also called client-server architecture and is shown in the following figure.

On the left in the picture are Anton with his laptop, Berta with her PC, and Charlie with his mobile phone. On the right is the WWW server. Between them is an unspecified network, which is often represented in diagrams as a cloud. This has led to the term “cloud computing” for Internet services, such as cloud storage, where one gets space for data on a remote server.

Anton, Berta, and Charlie now exchange messages with each other via the server. A client-server architecture is prone to failure, because without the server, communication between Anton, Berta, and Charlie does not work. In a dictatorship, it would be easily possible to switch off or monitor such a service.

An alternative is a so-called peer-to-peer network (P2P). Here, the software that was previously located on the server is distributed to all clients. Each participant is now also partially a server.

Such P2P applications, however, got a bad reputation due to file-sharing networks on which pirated music or films were exchanged. However, the P2P architecture is more failsafe and not easy to control. In dictatorships, they are therefore an important means of communicating securely. Another example of a P2P application is the cryptocurrency Bitcoin.

A “Complex” Model

The physical system was already dynamic but still easy to understand because the individual planets behave deterministically according to a fixed pattern. The planets already have dependencies, but these are constant and do not change. The planets cannot decide for themselves where they fly. It only becomes “complex” when the elements make their own decisions and can adapt.

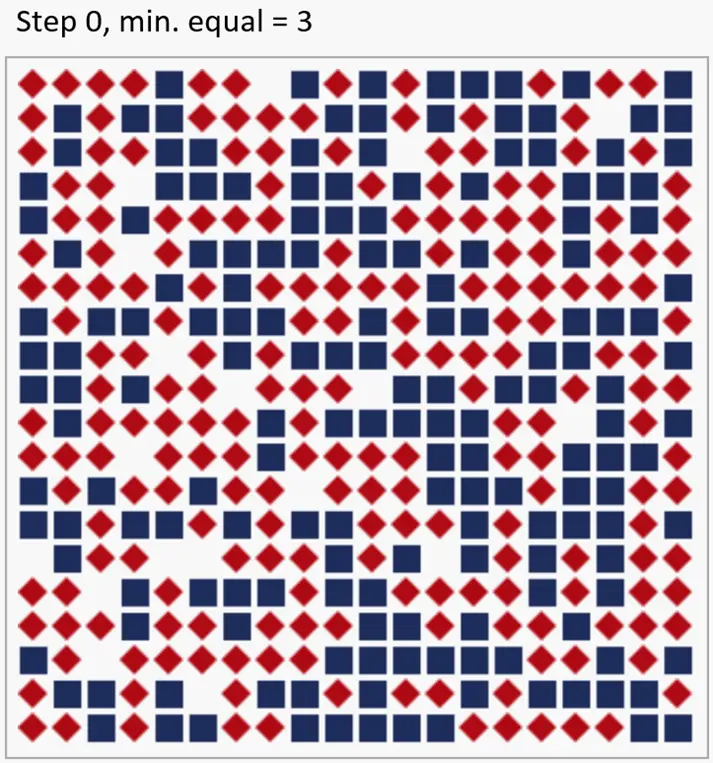

The Schelling model, named after its inventor Thomas C. Schelling, consists of m*n plots of land [Sch78]. A plot can either be vacant, or a red diamond-shaped or a blue square “agent” lives on it3. The field starts with a random distribution of red, blue, and empty fields. In the following figure, such a model is depicted:

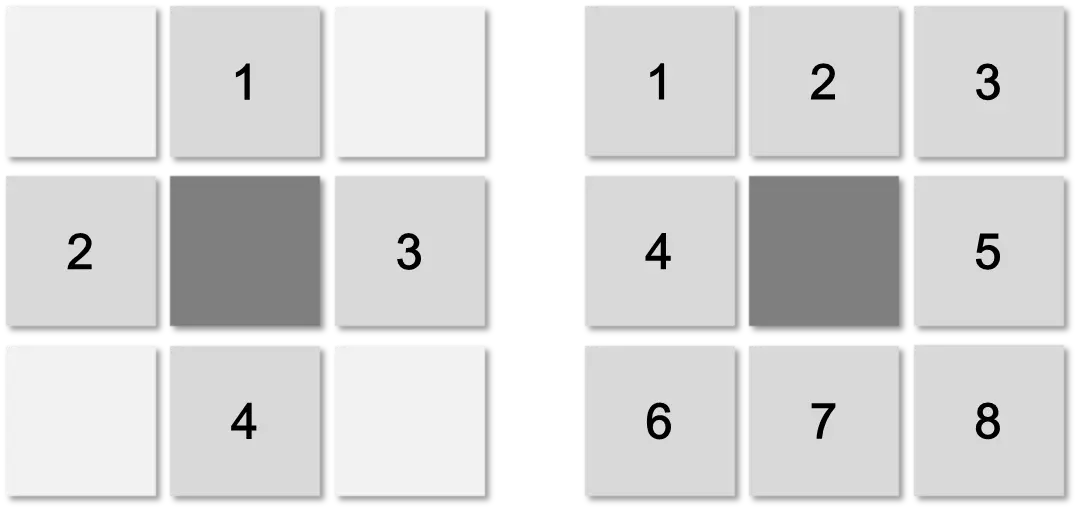

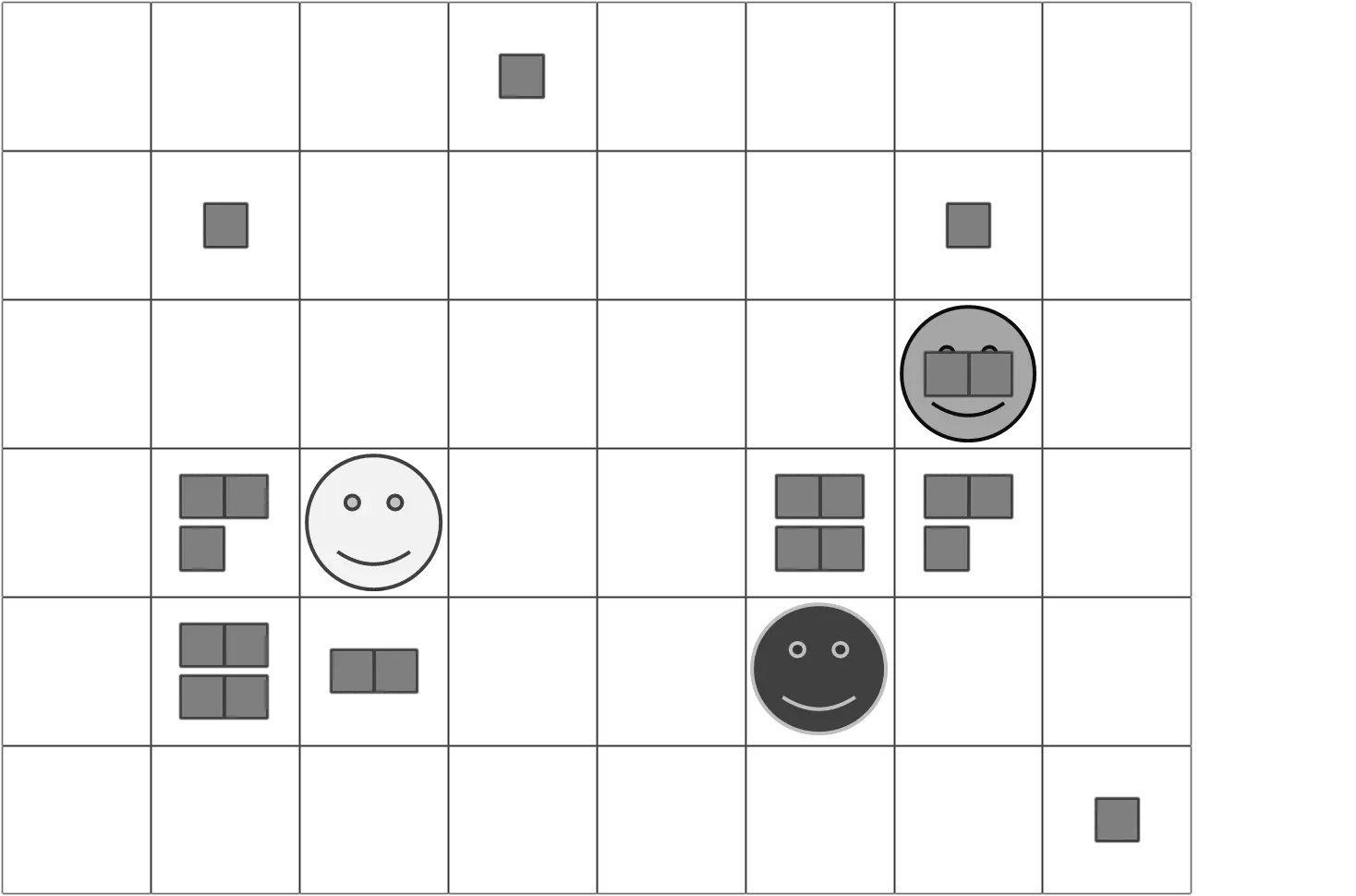

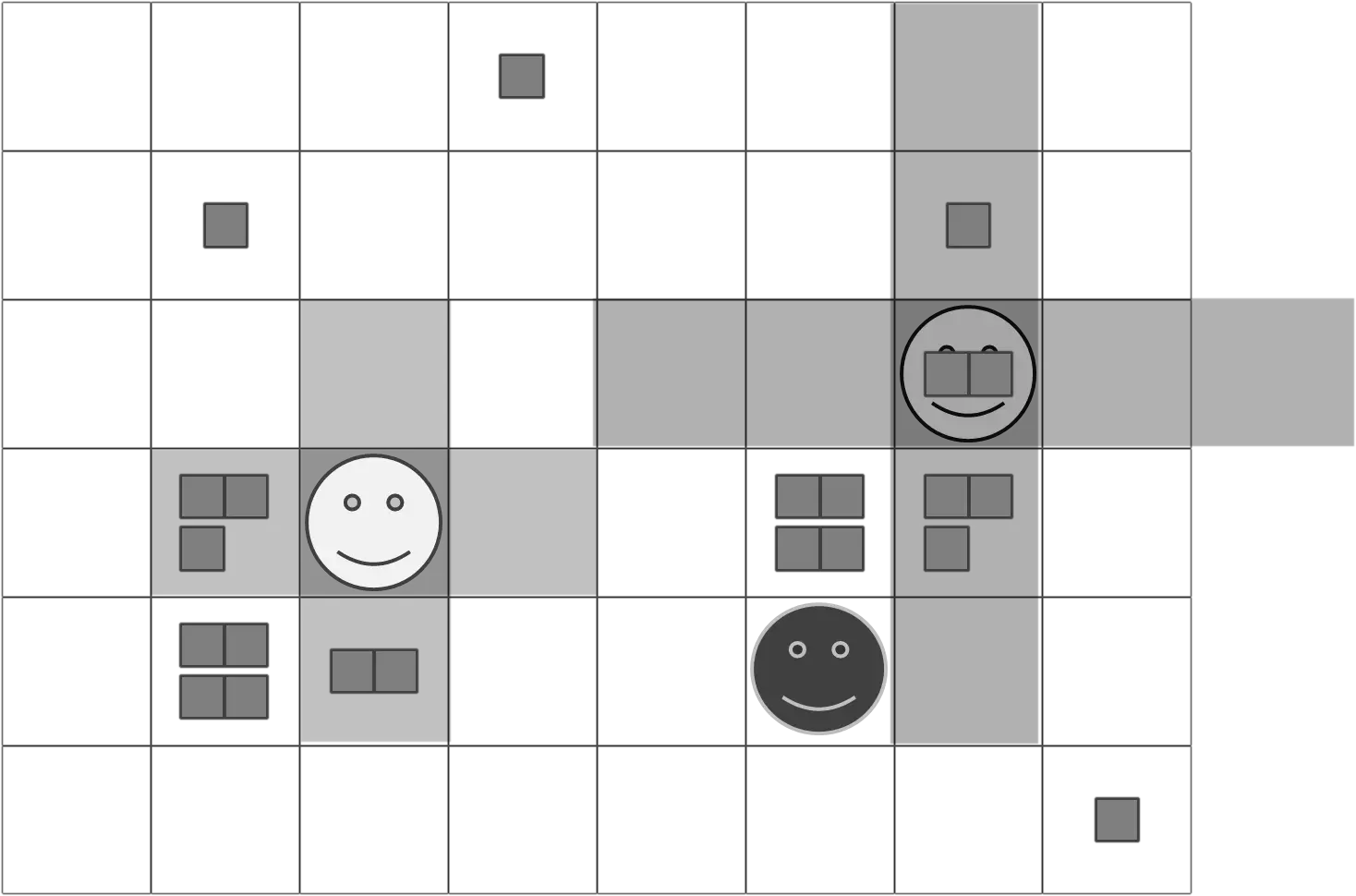

In each round, every “agent” looks at how many neighbors have the same color. If more than a certain number have a different color, the agent moves to another vacant field. The neighborhood of an agent consists of the fields around it. In the following figure, two different neighborhoods for an agent are shown:

The agent is in the middle. The Moore neighborhood on the left in the picture consists of only four neighbors: top, bottom, left, and right. The von Neumann neighborhood additionally includes the diagonal neighbors4.

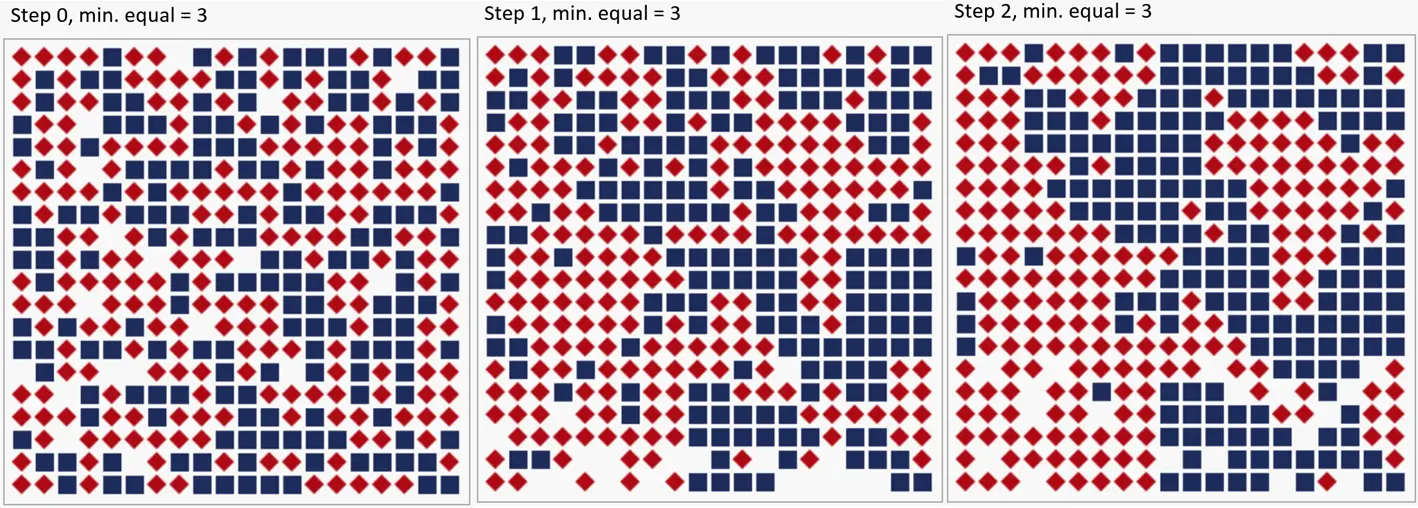

In our example, the agent is kept as simple as possible: In each step, he looks at his von Neumann neighborhood (with eight neighbors) and counts the different colors. If there are too few of the same among them, he moves to any still vacant field. One says the agent is “adaptive”; he changes his behavior based on his environment.

Question: What does the field look like after a few moves, even if the agent is willing to live in a “minority” with only at least 3 same neighbors out of 8?

Thomas C. Schelling conducted this thought experiment in the 1970s and still had to calculate it by hand. Today, it can be easily calculated with computer simulations. You can also try it out on the book’s website. With at least three same neighbors, the field develops as follows in the first two steps:

On the left is the initial situation, in the middle the first step, and on the right the second. Here it is already clearly recognizable that the two groups are separating from each other. How can that be? After all, the agents accept living in a minority of at least three same neighbors. Nevertheless, “housing blocks” with the same agents arise. In sociology, this is called segregation, from Latin meaning to set apart/separate.

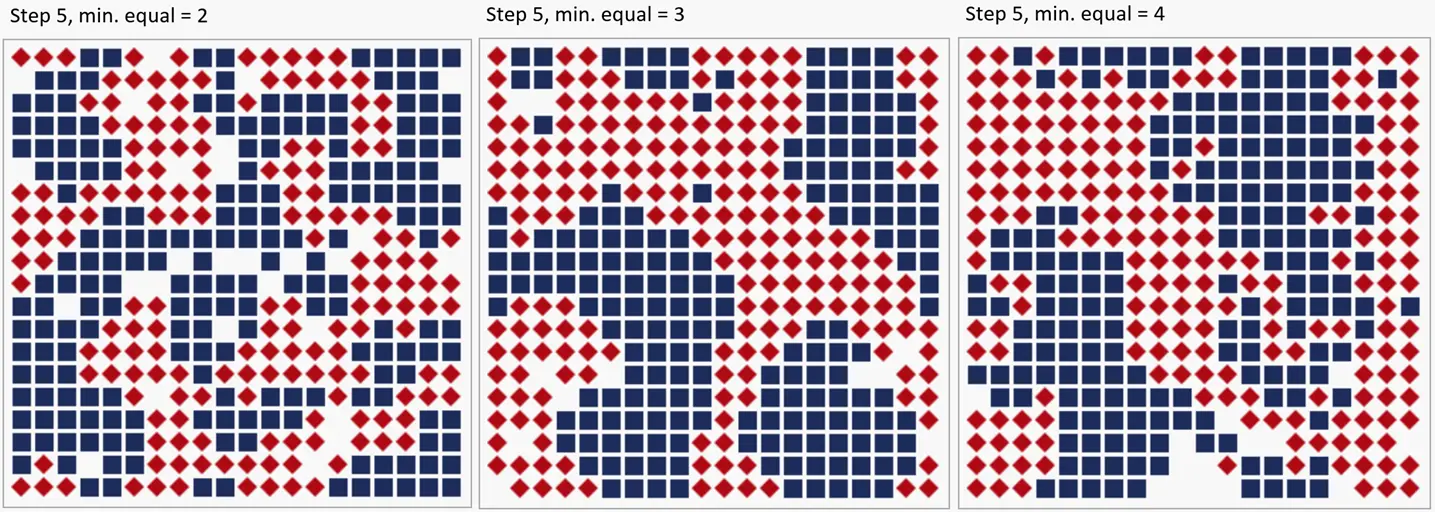

The following figure shows the fields after five steps for different minimum numbers of same neighbors: 2, 3, and 4:

Here, too, the “blocks” are clearly recognizable. A group behavior emerges that was not “programmed in.” Critics could already accuse the society in the middle, with at least three same neighbors, of “racism,” yet every single agent is tolerant. In a democracy, however, a majority of 51% is always needed, i.e., the agents must insist on at least 4 same neighbors to be able to reach a “draw.” Then, however, a clear separation already arises.

The group behavior was not explicitly programmed into the individual agents, but rather it emerged. One says the behavior is emergent. The problem with emergent behavior is that no one foresaw it. Here the sentence “the whole is more than the sum of its parts” really makes sense5.

Important: Emergent behavior arises unexpectedly through the repetition of interactions.

The problem for science is that this emergent behavior cannot be found out beforehand. You cannot tell by looking at the step() function. This consists of a simple rule: “IF (number of same neighbors <= 3) THEN move ELSE stay.” Global behavior arises from the individual local actions of the agents.

For mathematicians who like to use differential calculus, there is also a problem here: For this simple rule, no solution could be found with differential calculus so far [EK10]. In the first two examples with the three “planets,” that was still possible. There, for example, one could save a million calculations because one had this closed formula. That is not possible here.

Important: A system with emergent behavior is also called a complex system. Complex systems must be simulated. Mathematics cannot describe such dynamic processes.

This example is a simple variant of the model already published by Thomas C. Schelling in 1969. Schelling was a pioneer of complex systems, and his book “Micromotives and Macrobehavior”, published in 1978, was very influential [Sch78]. For his work in game theory, Schelling received the “Nobel Prize” in Economics in 2005 together with Robert J. Aumann6.

A model is an abstraction and a simplification of reality. This example is intentionally so minimalistic according to the principle of “Ockham’s Razor.” It is the smallest model that generates segregation. This simple model can, however, be the starting point for further investigations, because it could be extended in various ways [EK10, Bat07, RG11, EA96, MP07]:

- More than two different colors of agents “red” and “blue”

- Larger neighborhoods: all neighbors reachable in two steps

- Different thresholds for moving: Reds move with fewer than 3 same neighbors, Blues with fewer than 2 same neighbors

- The distance could be restricted during a move

- One could introduce rents or land prices

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM)

In the previous examples, we already used “agents.” Now it is time to clarify the term. An agent acts; he “operates.” The word comes from the Latin “agere” and means precisely “to act” or “to operate.” An agent lives in an environment and perceives information through its sensors. With its actuators, the agent can interact with the environment. An agent acts according to defined rules. In a simulation, a number of agents are “released” into an environment. In each time step, the agents are then allowed to perceive and act according to their rules. Agents form artificial societies that arise and change during a simulation. The goal of a simulation is to understand how and under what circumstances emergent behavior occurs. A “CompuTerrarium” is created [EA96].

One also speaks here of agent-based modeling (ABM) [RG11, EA96, WR15]. It is a new way of conducting science. Kenneth J. Arrow, who received the “Nobel Prize” in Economics in 1972 and found the famous Arrow theorem, said in 2006, “I am convinced that agent-based attempts in economics will become an important tool” [Eps06].

But ABM requires a rethink. Problems are formulated from the perspective of individuals and not from the perspective of the whole. The world is viewed from the “bottom” and not from the “top.” It is “bottom-up” modeling and not “top-down” modeling. The writer Leo Tolstoy (1828 - 1910) was one of the first people to describe this “bottom-up” perspective [Eps14]. In his work “War and Peace,” he wrote the following in 1812:

“To study the laws of history, we must completely change the subject of our observation, must leave aside kings, ministers, and generals, and examine the homogeneous, infinitely small elements by which the masses are guided.”

… and …

“Only by taking an infinitely small unit for observation (the differential of history, that is, the homogeneous tendencies of men) and attaining to the art of integrating them (that is, finding the sum of these infinitely small units) can we hope to arrive at the laws of history.”

This “differential” is the step() method. But as innovative as Tolstoy was here, he was also a bit mistaken, because as we now know, it is not enough “to calculate the sum of these infinitely small individual parts,” but we must “simulate the product.”

ABM has already been used with success in very many different areas. Dynamic processes can be represented very well with them. ABMs helped, for example, to clarify the following questions:

- How do social norms and customs arise? [Eps06]

- How do forest fires spread? [WR15]

- How do cities develop? [WR15, EA96, Bat07]

- How do epidemics and other diseases spread? [WR15]

- Where do traffic jams occur? [WR15]

- How can rainforests be used economically while also preserving biodiversity? [RG11]

- How do tumors grow? [WR15]

ABMs are still a fairly young development, and their distribution is constantly increasing. In the following, we will present a few ABMs.

Sugarscape

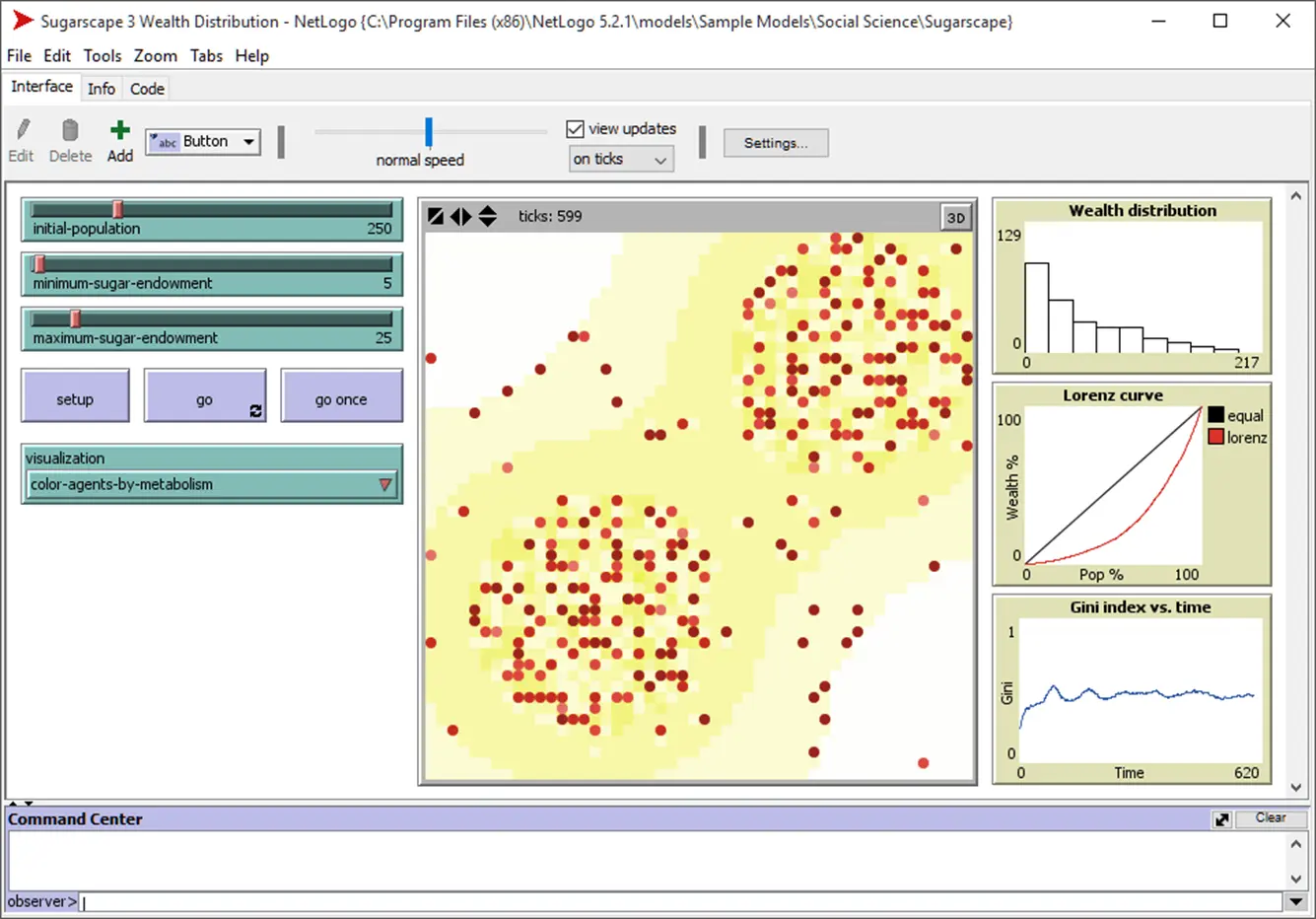

Joshua M. Epstein and Robert Axtell created a model called “Sugarscape” in 1996 in their book “Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up”, which is still often used today [EA96]. Sugarscape consists of a 2D grid of cells. In some of these cells, a random amount of sugar grows in each time step. The agents have a metabolism and require a randomly determined amount of sugar in each time step. They can harvest this sugar from the field they are currently on. Sugar that they do not consume, they keep as a reserve. A maximum of one agent can be in each cell. A “Sugarscape” is sketched in the following figure:

Sugar is symbolized by the small blocks. There are three agents: Light, Medium, and Dark. Only “Medium” has something to eat. The other two are standing on fields where there is nothing. The agents have a randomly determined visual range with which they can search their surroundings for sugar, as sketched in the next figure:

The light agent with a visual range of 1 only sees the nearest neighbors; the medium-gray agent with a visual range of 2 also sees the neighbors of the nearest neighbors. The agents cannot look diagonally; they consider their Moore neighborhood.

In the simulation, it is determined at the beginning how much sugar is in each cell. Then the agent population is defined and the metabolism and visual range of each agent are established. In the step() method, the agent carries out the following steps:

- How much sugar do I find in my surroundings within my visual range?

- Is that more sugar than on the field I am currently standing on?

- If yes, go there, otherwise stay

- Take the sugar from the current cell

- Eat enough sugar; if not enough is available, “die” and drop out

And so it continues for each time step. The following figure shows a screenshot using the tool NetLogo.

There are many variation possibilities here:

- The size of the field and the number of agents

- How much sugar can be on a cell?

- How fast does the sugar grow? Fast or only slowly, e.g., one piece per time step?

- Agents could have a limited lifespan. After t time steps, they then die automatically. A new agent is added randomly as a replacement.

Epstein and Axtell go through various possibilities in their book. In this simple “play world,” three characteristics known from reality can already be shown [EA96]:

First, an environment can only sustain a certain amount of living beings; it has a “carrying capacity,” as in ecology. If too many agents are created, the environment can no longer feed them. This may seem trivial at first glance, but in a more complex model, one could model real agricultural systems and calculate how many people can feed themselves from this agriculture.

Secondly, in simulations with a high number of agents above the “carrying capacity,” it becomes clear that “selection” occurs. Agents with a high visual range and low metabolism are more likely to survive than others.

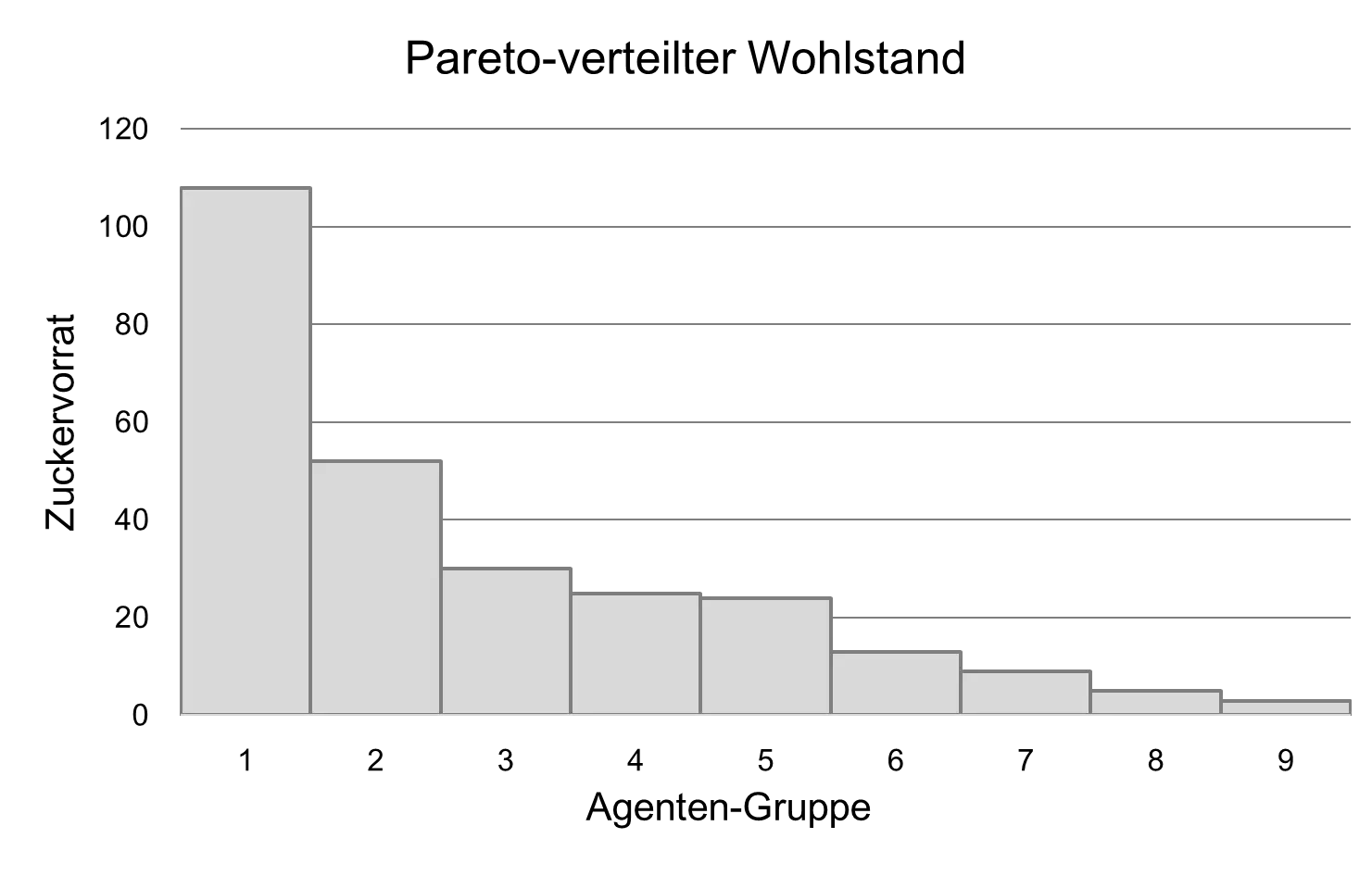

Thirdly, the agents can collect a sugar supply; they can achieve wealth. The “distribution” of the agents’ assets was analyzed here and it was found that it is a so-called Pareto distribution, named after Vilfredo Pareto (1848 - 1923). This wealth distribution is an emergent property and is represented in the following graph:

The rich agents therefore have much more sugar than the poorer ones. This means: wealth is unequally “distributed.” Incidentally, Pareto had found this distribution when he examined real incomes in Italy. This type of distribution is found in many complex systems. Another example of a Pareto distribution is the distribution of words in an English text. There are words that occur much more often than others, such as “the”, “a”, “is”, “of”, etc.

It should be noted here that the term “distribution” comes from statistics and refers to how frequently certain values occur, how they “distribute” themselves. It does not mean that there is a “distributor” somewhere. There is no one who carries out this distribution. If one were now to call the above distribution an “unjust distribution,” then that does not get to the heart of the matter, because no one in this model is “unjust.” No agent does anything to the others in this model. They all just work away for themselves. Complex systems have no internal or external control, but they “regulate themselves.” A “spontaneous order” arises. This “order” does not, however, have to be in the interest of the observer and can also create great inequalities.

In this model, the inequalities arise because the agents have different metabolism and visual abilities. Furthermore, the sugar is distributed unequally. Here in the simulation, “first come, first served” currently applies. Anyone who happens to be on a sugar-rich cell at the beginning by chance has advantages. The emergent “bottom-up” behavior therefore shows undesired results.

The opposite of “bottom-up” is “top-down,” and here in the simple example, one can already consider how one could adapt this economy to one’s own ideas of “justice” through “interventions.” Is it better if everyone has the same amount of wealth? How could that be achieved? “Simply collect and distribute” sounds easier than it is, because this “redistribution” must also be carried out by agents. One needs agents who collect sugar and distribute it to the poorer. But who determines how much sugar is collected and who is poor enough to receive some? Is that decided centrally for everyone? Do you also have to implement politicians and a whole democracy with these “redistributors”? The redistribution must be done by agents who also have to eat sugar because they too have a metabolism. Are they allowed to eat from the collected sugar? An agent with a high metabolism could become a redistributor because that is the only way he can get to the lots of sugar.

The Sugarscape model may seem simple and trivial at first, but a lot of political questions arise here that are not at all easy to solve or implement. As a programmer, you cannot simply say at this point “the state must do that” and leave it at that, because the state would also have to be programmed first. And before you can do that, you have to ask yourself “exactly how should the state actually do that”? What means are actually available to it? Who pays for it? Who ensures that the “redistributors” do not constantly increase their “stipends” (here with sugar, the term “diet” takes on a whole new tone).

Sugar and Spice

In the course of their book, Epstein and Axtell examine many extensions of the basic model [EA96]:

- Migration through seasonal effects: When seasons are introduced and sugar grows more slowly in some regions, migratory movements can be observed.

- Environmental pollution: If the mining of sugar generates dirt, then polluted areas arise and the agents have great difficulty feeding themselves.

- Genders and reproduction: If the agents are given a gender and they can have children, it can be investigated which characteristics reproduce and how the population develops.

- Cultural attributes: How do certain opinions spread? How do networks arise? How do “tribes” of agents emerge?

- Aggressions: What happens if aggressions are allowed?

- Spice as a second good: If there is a second commodity “spice” in addition to sugar and the metabolism of the agents is changed so that agents need both to live, then barter trade with the neighbors arises. Here, economic phenomena can be investigated, such as at what prices the two goods are traded.

All these examples make it clear that complexity can be generated with very simple means. Many questions that have not yet been solved by science and politics arise here. But ABM can help to find answers to these questions.

Why did the Anasazi move away?

The “Long House Valley” in Arizona in the southwest of the USA was inhabited for centuries by Anasazi Indians. But quite suddenly around 1300 AD, the entire population left this valley and it was thereafter no longer inhabited for a long time. Some researchers suspected a drought period as the cause.

Starting from their Sugarscape model, Epstein and Axtell developed a model of this valley [Eps06]. The valley is 96 square kilometers in size and is located today in a Navajo Indian reservation. Extensive data about the climate and the environment in this valley existed due to research work. The climatic conditions in the valley allowed, for example, the exploration of agricultural use in the past. Through excavations, insights were gained into the various cultural development stages of the population over time. It had been found that from 7000 to 1800 BC, hunter-gatherers sparsely populated the area. Around 1800 BC, agriculture began with the cultivation of maize and then led to the Anasazi culture until its sudden disappearance around 1350 AD. For agriculture, geological knowledge about the condition of the soil and water occurrences is very important.

Data from very many different projects and databases had to be compiled. It must be explicitly emphasized that this work could only be done because there was reusable data from previous research work. Without this “data collection,” this simulation would not have been possible. Researchers are needed here who are sufficiently familiar with handling data so that they store the data in the correct scope and format. Researchers with data and data analysis knowledge are needed.

The simulation was calculated from 800 BC to 1350 AD. In this model, households were used as “agents” because the exact number of inhabitants and their behavior were not known, while the number of approximately 200 households was known due to excavations.

The result of the simulation is that it was not due to a persistent drought alone that the entire population left the valley. For although the valley had become drier, it would still have been enough for a few inhabitants. The fact that all inhabitants left the valley together must therefore also have had social reasons. The inhabitants probably did not want to separate from each other.

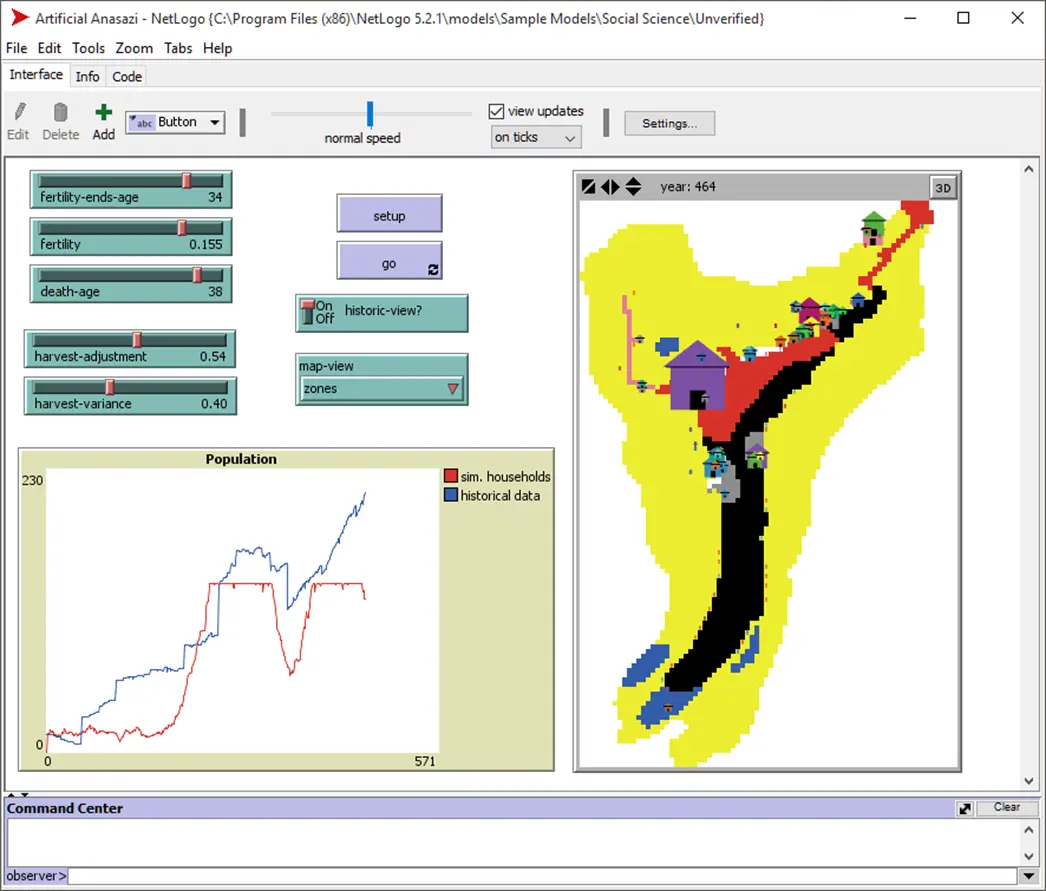

The model is also available in NetLogo. The following screenshot shows an excerpt from the simulation.

One can see from the screenshot that the absolute population figures were not correctly predicted in this model, but that was improved in a later model [Eps06, Chap. 5]. The American historian Jared Diamond wrote in the American journal Nature about this project that it represents a “new standard in archaeological research.”

“More Human” with Agent_Zero

In traditional agent-based modeling, agents are often quite mechanical because they only work through simple IF-THEN conditions. But social phenomena can only be investigated with “more human” agents. Therefore, Joshua M. Epstein has developed a “software individual” that he presents in his book “Agent_Zero: Toward Neurocognitive Foundations for Generative Social Science” [Eps14]. Agent_Zero is intended to behave “more humanly,” also make mistakes, and not be a perfect “homo oeconomicus.” To this end, it has three different “components”:

- Feelings: emotional, feeling-related (“affective”)

- Thinking: cognitive, deliberative (“deliberative”)

- Social: Network with others who can influence him

These components can also have opposing opinions: Agent_Zero therefore has an “inner life,” possibly also with contradictions. Agent_Zero is intended to represent the complexity of human behavior better in this way.

This sounds better, of course, than it is in reality: Agent_Zero consists of three functions whose results are added together. They are relatively simple formulas, but they were designed based on findings from neuroscientists. These formulas are also, in Epstein’s opinion, anything but perfect and are only to be understood as a first approach. In his opinion, however, they fulfill their task, because his goal is not the modeling of the individual, but of society. When several of these simple agents “come together,” they generate social behavior that he wants to investigate.

To this end, he simulates, for example, the Arab Spring of 2011, the emergence of business cycles in the economy, or American court cases in which the hearts and minds of jurors are to be won.

Complex Economics

The economist W. Brian Arthur has investigated economic problems with the help of complex systems and ABM. Since the 1980s, he has been working on “complexity economics.” For example, he has examined the following topics with ABM [Art14]:

- Manipulation of financial systems

- Behavior of stock markets

- Technological competition and economies of scale (“increasing returns”)

- How inventions work

Complex economics will be covered in more detail later in Chapter 5.

You as an Agent Yourself

You are the agent, and other people are too. The environment is the real world. What would have to be programmed into the step() function? Do you also think about holidays or retirement? If you want to buy a car, how much credit should you take out?

What would the agent have to consider? Economic behavior, in any case. But to do that, you would first have to become aware of why you make your purchases the way you make them. Most purchases, for example in the supermarket, are made out of habit and without much thought. Why do I buy a certain yogurt and how do I teach the agent this? Traditional economics sees the economy from a bird’s eye view (“top-down”); they calculate aggregates and make models with differential equations.

In agent-based modeling (ABM), a completely different perspective is required: “bottom-up.” Here in this example, it corresponds to the ego perspective.

Complex Systems

Classification

We have now become acquainted with various models. The examples have shown: Whether a system is simple or complicated depends on various factors:

- Number of elements or nodes

- Complexity of the individual nodes, in particular the

step()function - The number and “complexity” of the relationships between the elements

Systems can be categorized colloquially as follows [Pea15]:

- Simple (“obvious”)

- Complicated (“complicated”)

- Complex (“complex”)

- Chaotic (“chaotic”)

These are not scientific definitions, but they can be used well in everyday life.

In a simple system, cause and effect are clearly recognizable. There are no side effects. Everyone can apply learned recipes here, such as at IKEA™ or LEGO™.

In a complicated system, on the other hand, the analysis of cause and effect already requires some effort and expert knowledge. Optimal solutions can be calculated with some effort. The knowledge for solving tasks in complicated systems is taught in schools and universities. Solutions arise from the combination of existing knowledge. A detective story is a good example here, but not the simple ones on TV, but rather Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, or John Dickson Carr.

In complex systems, the relationship between cause and effect is only apparent in hindsight. Optimal solutions are very difficult to find or do not exist. Solving the complex system often exceeds the abilities obtained in formal education. One must invent something new or apply existing knowledge in a new way.

A chaotic system, on the other hand, is a hopeless case. It is not possible to determine rationally what is cause and what is effect.

A strict distinction must be made here as to whether a system is complex or whether it is only seen as complex. Chess, for example, was once seen as complex; on closer inspection, however, it is a simple mathematical optimization problem and is today only seen as complicated because the creation of chess programs is still complicated today. Whether a system is seen as simple, complicated, or complex therefore also depends on education, knowledge, and the available technology.

Properties of Complex Systems

Complex systems show emergent behavior and, moreover, often possess other special properties [Hol14, EK10, MP07, Mit09]:

- Self-organization: Complex systems have no internal or external control, but they “regulate themselves.” A “spontaneous order” arises. This “order” does not, however, have to be in the interest of the observer. An example of this is flocks of birds.

- Adaptivity: The agents of the system adapt, and through this, the whole system adapts. This adaptation can take place through learning or through evolution.

- Decentralization: There is no central control, only self-control of the individual elements.

- Each component has relatively simple rules. The overall system has complex behavior.

- Diversity: Some complex systems become even more complex in the course of their existence, as the diversity of elements increases. In a jungle, for example, new animal, insect, and plant species arise.

- Butterfly effect: Small differences in the initial configuration can have large effects and lead to completely different results. Can a butterfly in Brazil trigger a tornado in Texas? [TG15]

In some books, a distinction is made between “complex physical systems” (CPS) and “complex adaptive systems” (CAS). Others distinguish between “complex systems” and “complex adaptive systems.” For reasons of simplicity, we do not do that here.

Differential Equations

The traditional scientific means of describing dynamic systems are differential equations. Similar to the step() method, these express differences regarding time. For a passenger car, this differential is, for example, the speed and is given in km/h. For many simple and complicated systems in science, these differential equations are often the best choice7. But they have their difficulties with complex systems.

Important: Differential equations are not suitable for complex systems; these must be simulated with ABM.

Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), Part 2

ABMs therefore have many advantages compared to differential equations, because only rudimentary programming skills are needed and the “bottom-up” perspective is much more natural [Eps06, RG11, EA96]. ABMs are easier to understand and often offer causal explanations, while mathematical methods usually consist only of numbers and are “number crunching.” Another advantage of ABM is that there is a fluid transition between simulations and computer games [BP12].

The goal of agent-based modeling is to generate and investigate certain emergent behavior of systems. It is a new scientific instrument for a “generative science” and generates “generative explanations” [Eps06, WR15].

Currently, however, ABMs are not yet very widespread: humans have traditions and habits. If someone has already invested a lot of time and work in a scientific method, why should he learn a second method and start again from scratch? A comparison of scientific progress with a hike through a mountain range helps here [CK14]. The individual mountains represent the scientific methods, and the higher one gets, the more the mountaineer or researcher knows. The knowledge is hidden in the mountains and the scientist looks for a way through. On the hike, he has already climbed quite far up a mountain. But then he discovers a still higher mountain in the distance, on which he would have even better insights. The problem, however, is that he would first have to descend a good bit in order to then climb the higher mountain again. He would therefore start again at a lower level. The progress on the first mountain prevents or delays a descent and a continuation on the second mountain. This problem is called “Twin Peaks” in English literature, like the legendary TV series from the 90s by David Lynch8.

But even if ABM is not so widespread today, it is important to view the problems from the “complex” perspective.

For beginners, the following software tools for ABM are available, among others:

- NetLogo is a variant of the programming language Logo and adapted to ABM. It is open-source, has turtle graphics, and there are many examples, see http://netlogoweb.org. Suitable introductions are the books “An Introduction to Agent-based Modeling” by Uri Wilensky and William Rand [WR15] and “Agent-Based and Individual-Based Modeling: A Practical Introduction” by Steven F. Railsback and Volker Grimm [RG11].

- Repast consists of several open-source products and offers a development environment based on Eclipse. Programming is also done in a variant of Logo, called ReLogo, or in Groovy or Java, see http://repast.sourceforge.net/. Previous knowledge in software development with Eclipse is recommended.

- StarLogo TNG is more for children learning turtle graphics and graphical elements, http://education.mit.edu/portfolio_page/starlogo-tng/.

- MASON is a library written in Java for multi-agent simulations. It is aimed more at software developers, http://cs.gmu.edu/~eclab/projects/mason/.

- AnyLogic is a commercial platform also used in industry, of which there is a version for private use for learning available for download, http://www.anylogic.com.

Interventions

Human Action in Complex Systems

Psychologist Dietrich Dörner, in his book “The Logic of Failure,” described the difficulties people have when dealing with complex systems [Doe03]. Dörner and his staff developed a computer simulation of an agricultural system in Africa. The relationships between the individual variables in this model were explicitly designed as a complex system. The “player” has dictatorial powers in the simulation, i.e., he can intervene in the economy at will. He can have wells built, fertilize farmland, etc. Dörner’s goal was to investigate how test subjects handle such a complex system. What do they do right? What do they do wrong?

The simulation runs in a series of time steps. At the beginning of each time step, the player is given the opportunity to obtain information about the state of the “economy.” Subsequently, he can initiate actions. The simulation then calculates the next state, and the next time step follows.

One result of the investigation is that players do not intuitively master the handling of complex systems. There are the following difficulties [Doe03]:

- After the first acquaintance with the system, the players overestimate their knowledge of the system and underestimate the complexity of the system. They are no longer self-critical enough.

- The delayed feedback of the system is also difficult. They may only see negative repercussions later at a completely different point. Therefore, they often cannot causally relate cause and effect.

- Under time pressure, “players” start to “overdose” their actions. The system will then swing strongly in one direction; the player then steers too strongly against it, and the problems build up.

- Players tend to think in linear causal chains (A -> B -> C) rather than in causal networks. Therefore, they often misjudge side effects and long-term effects.

- After wrong actions, players omitted the necessary self-criticism and self-correction and continued as before or simply delegated difficult tasks to others.

- Often, exponential growth is not seen at first. These are processes where something grows very strongly and will be treated later in Section 9.1.

Dietrich Dörner compares a complex system to a game of chess in which the pieces are hung together with rubber threads and influence each other. This makes it impossible to move only one piece. The player always moves other pieces too. Sometimes it is even worse and there are unobserved variables. Then part of the playing field is not visible to the player and is obscured. The player only has incomplete information [Doe03]. In complex systems, one must think holistically and always observe the overall situation; one must always keep several aspects in eye, because more than one aspect is affected by every intervention. Dietrich Dörner summarizes it as follows: “in a world of interacting subsystems, one must think in interacting subsystems if one wants to have success.”

Important: When dealing with complex systems, “complexity” must be taken into account.

Decisions in Complex Systems

If something is wrong in a complex system and one wants to intervene “politically” and “top-down,” such as with the sugar distribution in Sugarscape in Section 2.4, then one must think of a means with which the goal can be achieved without triggering fatal side effects. In simple systems, this is quite easy:

- Think of a goal to be achieved

- With what means can the goal be achieved?

- What side effects do the means have in each case?

- Choose the means with the lowest side effects

- Apply the means

And exactly that is not so simple in complex systems, because in step 3, the side effects can only be determined if one knows the system well. The decision in step 4 is also difficult because many criteria have to be weighed against each other here. In complex systems, decisions are made more difficult by the following facts [Doe03]:

- Complexity and interconnectedness: interdependent variables

- Intransparency: not all variables are visible or measurable

- Dynamics: The system develops further and changes; it has its own momentum

- Uncertainty: Incomplete or false information about the system

There are the following sources of uncertainty:

- Unobserved variables

- Unknown dependencies of variables

- Unknown effects of the actions and deeds

In the language of networks and graphs, there are therefore unknown nodes and unknown edges. In complex systems, the relationship between cause and effect is not trivial and an action or a means often has more than one effect. Decisions in complex systems are thus also “complex decisions.” Decision theory forms the basis for optimal decisions. Based on the available information, the optimal decision is determined with the help of probability calculation [Pet11]. In complex systems, however, this information is uncertain, and therefore it is very difficult to find the “right” decision. Humans cannot usually handle complex systems because they cannot foresee the consequences of their actions. Political “top-down” interventions are therefore to be enjoyed with caution. We will go into this later in the political chapter in Section 11.5.

Black Swans and Antifragility

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is a philosopher, statistician, and risk analyst who has caused a stir in recent years with a series of books. He worked as a financial mathematician in several Wall Street companies for some years. He dealt with financial derivatives and hedge funds and was exactly in the center of “casino capitalism.”

In “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable” [Tal08], he shows that people are generally blind to extraordinary events. He illustrates this using the black swan. Before the discovery of Australia, people thought that all swans were white and that swans could not have any other color. That was right on the one hand from experience, because until then only white swans had been seen. But after all, there are other black birds, such as ravens. But a black swan was thought to be impossible. Nassim Taleb pursues this thinking error as to why people hold something for impossible that is actually only improbable.

A “black swan” is for Taleb an extraordinary event that has big consequences and can always be explained by people in hindsight according to the motto “one is always smarter afterwards.” Examples of “black swans” are, for example, the financial and economic crises or the attack of September 11, 2011, on the World Trade Center.

The problem is that “black swans” are usually not considered when formulating laws and regulations. Also, when modeling technical systems, it can be that one forgets “black swans” and does not include them in the model. An example of this is the faulty risk models before the financial crisis of 2008.

Important: In complex systems, there can be “black swans.”

In his book “Antifragility: Things That Gain from Disorder” [Tal12], Taleb divides systems into the following three classes:

- Fragile systems

- Robust systems

- Antifragile systems

A fragile system is breakable. It does not cope with wrong inputs or actions. It is dependent on freedom from disruption. Things must go exactly as planned, with as little deviation as possible. Typically, human-made systems are fragile.

A robust system also copes with wrong inputs. In some robust systems, even subsystems can fail without loss of functionality. This is achieved with redundancy. In an airplane with two jet engines, one can theoretically fail. A system that can deal with errors is also called a fault-tolerant system. It should be taken into account here that some systems only cope with a limited number of errors. The last jet engine, for example, would not be allowed to fail as well.

An antifragile system, on the other hand, gains stability from disruptions. These systems are so far mostly found in nature. Humans cannot yet create these systems artificially. When a person trains athletically by, for example, going jogging, the muscles and tendons gain from the “disruption.” The body improves through the “disruption” or the training and rebuilds the muscles.

When composing systems from subsystems, one must take into account that the properties of subsystems are not transferred to the overall system. The overall system can have a different class than the subsystems.

An overall system made of fragile redundant subsystems is, for example, robust and not fragile. An economy as a whole is robust if the individual companies are fragile, i.e., can go insolvent. Here, the individual fragile parts are simply replaced. A banking system, on the other hand, in which the individual banks cannot go insolvent, is not robust but fragile. For the banks that accumulate losses are not replaced here, but can continue with their misconduct.

Important: If you make subsystems more robust, the overall system can become fragile.

Nassim Taleb has also dealt with complex systems and interventions [Tal12]. In “Antifragility,” he writes:

“A complex system does not require – contrary to common opinion – complicated systems, regulation methods, sophisticated political strategies. The simpler, the better … Since things are not transparent to the last detail, an intervention has unforeseen effects.”

The findings of Nassim Taleb are extremely important for the modeling of systems.

-

Note: The colors red and blue are of course symbolic and can stand for any difference. One could also use numbers, such as zero and one. The model originally comes from the USA, because researchers had asked themselves how Chinatowns or black neighborhoods could emerge [Sch78]. ↩

-

The neighborhoods were named after Edward F. Moore (1925 - 2003) and John von Neumann (1903 - 1957). ↩

-

Mathematically, the statement “the whole is more than the sum of its parts” is of course true. According to category theory, there are two different operations between two elements: the sum and the product. And the product is generally—colloquially speaking—the “larger” operation [Spi14]. The whole is therefore the product of its parts, not its sum. In set theory, for example, the disjoint union is an example of a sum and the Cartesian product is an example of a product. The sum of the sets {A, 1} and {B, 2} is thus {A, B, 1, 2} and the product is {(A, B), (A, 2), (1, B), (1, 2)}. The sum loses the information about where the elements come from, whether from “left” or “right”. The Cartesian product, on the other hand, retains all information. The Cartesian product is more than the disjoint sum of its parts. ↩

-

The “Nobel Prize” for Economic Sciences was put in quotation marks because the full name “Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize for Economic Sciences” is a bit unwieldy and it actually does not belong to the original “real” Nobel Prizes. ↩

-

So-called ordinary differential equations (ODE) have only one independent variable and can be solved simply (if they are linear). However, many problems have more than one independent variable and must be described with partial differential equations (PDE). These often have no simple closed solution and must be calculated for each time step. This is done today with powerful computers and is often very time- and computation-intensive and can sometimes take up entire data centers. A large part of the computing time of the Top 500 supercomputers (http://www.top500.org/) is spent solving PDEs. Solving PDEs is still a subject of research today and also a mathematical art. Many scientific articles are written on this every year. PDEs therefore have a long learning curve and require several years of mathematical study. ↩

-

Scientists who have first painstakingly worked their way into PDEs over the years naturally do not give them up so quickly. And the scientific world is also partly very conservative, partly very skeptical of new things. Therefore, ABM will only establish itself “bottom-up”, i.e., be used in private initiative and thus gain distribution. ↩