AI Took a Different Path Than I Expected: Looking Back at 2016

December 30, 2025

In 2016, I wrote the following in “Die komplexe Perspektive” (“The Complex Perspective”):

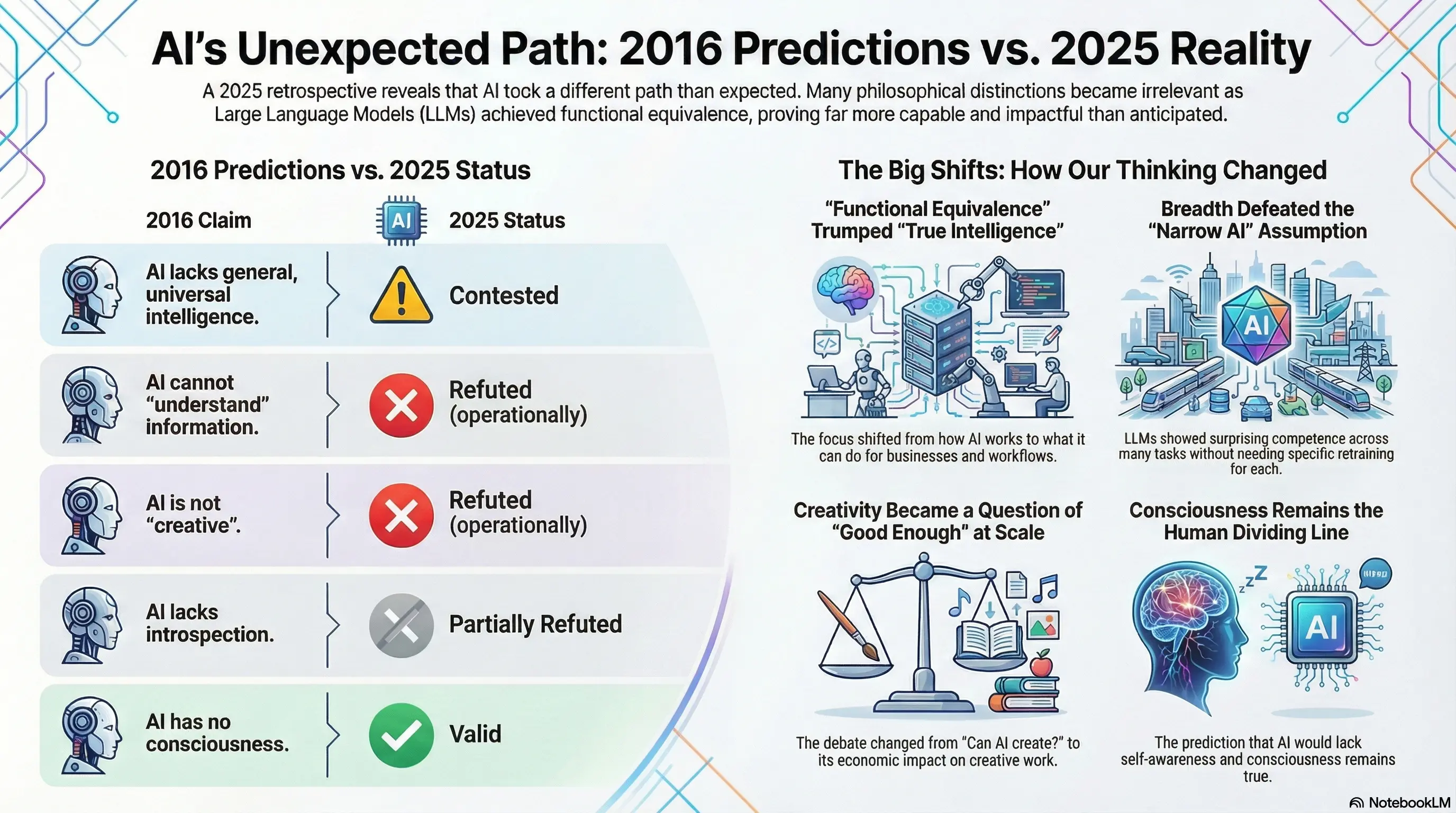

However, it must also be stated clearly that AI has not achieved its ultimate goal of “intelligent agents.” And at present, it does not look as if universally intelligent agents will exist in the near future (up to 2025). This is because artificial intelligence today still has the following limitations:

- AI systems do not possess general, universal intelligence; they are specialists and are used only in small, well-defined domains.

- AI systems cannot “understand” information.

- AI systems are not “creative.”

- AI systems lack introspection and cannot “understand” themselves.

- AI systems have no consciousness and no self-awareness.

- Today’s AI systems at best only appear intelligent, but they are not truly intelligent.

And it turned out I was not right. Let me explain why.

AI systems do not possess general, universal intelligence

Status: Contested, but less clear-cut than expected.

In 2016, AI was indeed narrow. Systems excelled at specific tasks—playing Go, recognizing images, translating text—but could not transfer learning across domains. This was a factual observation, not speculation. The assumption that this would remain true until 2025 turned out to be overconfident.

What changed: Large language models (LLMs) trained on vast text corpora developed surprising breadth. A single model could now translate, summarize, write code, explain concepts, and generate creative text without task-specific retraining. This was not artificial general intelligence (AGI), but it wasn’t narrow AI either.

The distinction collapsed not because machines achieved general intelligence, but because the category “narrow” ceased to be useful. Modern LLMs occupy an intermediate space: broad competence without universal capability. They remain specialists in language-mediated tasks, but language turned out to mediate far more tasks than expected.

Back in 2016 Intelligence was domain-specific by design. The idea that statistical learning over language alone could produce cross-domain competence seemed implausible. I underestimated what scale and architecture could achieve.

AI systems cannot “understand” information

Status: Refuted as stated, but philosophically contested.

The claim rested on a distinction from the “syntax vs. semantics argument”: computers manipulate symbols (syntax) without grasping what the symbols mean (semantics).

What happened: LLMs demonstrated semantic competence without semantic primitives. They did not learn predefined ontologies or map tokens to real-world referents. Instead, deep learning over sufficiently rich data forced models to internalize constraints that behave like semantics. An LLM “knows” what a cat is, because it has seen the word a million times used in various contexts and found out when and for what the word cat is used—the “latent structure”.

This inverted decades of assumptions. The traditional “symbolist” view held that concepts/meaning exist first, then symbols/words map to those concepts, then reasoning manipulates the symbols using logic, and finally language expresses reasoning. The underlying assumption was that meaning is grounded in the world, then encoded into symbols. Systems needed explicit semantic representations (ontologies, knowledge bases) to “understand.”

Meaning → Symbols → Reasoning → Language

The new reality reverses this flow:

Language → Latent Structure → Reasoning-like Behavior → Functional Meaning

What LLMs show (bottom-up): they start with text (tokens), patterns emerge from statistical learning, the model produces coherent logical-seeming outputs, and meaning appears as reliable behavior rather than explicit representation. The inversion: meaning emerges from language patterns, not from pre-existing concepts. LLMs don’t have explicit semantic representations; they learn constraints that behave semantically.

The philosophical question remains unresolved. Do LLMs “really” understand, or do they merely exhibit meaning as behaviour? The pragmatic answer: meaning manifests as reliable behavioral patterns. For engineering purposes, the distinction between “true understanding” and “functionally equivalent behavior” may not matter.

In 2016 it was an open question if the “connectionists” were right, if there will be understanding if the neural network is large enough. That this at some point in time worked after training with a lot of data was not what I expected.

AI systems are not “creative”

Status: Refuted operationally, contested philosophically.

For decades, creativity functioned as a human moat — the final cognitive capability that would remain categorically human. The reasoning seemed sound: creativity is non-algorithmic, requires intention and context, and involves generative leaps that machines could not replicate.

What happened: Generative models produced novel images, coherent narratives, functional code, and even analogical reasoning. They were not genius, not conscious, but competent enough at scale to substitute for much human creative work.

The key insight: creativity is not a binary property. Humans vary enormously in originality and fluency. Machines did not need to match peak human creativity—they only needed to be useful, cheaper, and faster than the alternative. AI-generated marketing copy is serviceable for most purposes, though rarely award-winning. Design tools produce dozens of logo variations, with humans selecting the best. Music generation sounds competent but rarely transcendent.

The moat collapsed not because AI became “truly creative” in some philosophical sense, but because “functional equivalence” made the distinction economically irrelevant. Organizations shifted from asking “can it create?” to “is it good enough?”

In 2016 creativity was conceptually anchored to consciousness and intentionality. The assumption underestimated what pattern learning at scale could accomplish. I thought creativity was an all-or-nothing thing, and I didn’t realize that even “average” creative ability from AI could already change the economy in a big way.

AI systems lack introspection and cannot “understand” themselves

Status: Partially refuted, evolving rapidly.

In 2016, AI systems had no capacity for self-reflection. They could not examine their own reasoning, identify their limitations, or adjust their behavior based on internal assessment.

What changed: Techniques like “chain of thought” prompting gave models the ability to articulate intermediate reasoning steps. This is not introspection in the human sense—the model does not “think” about its own thoughts. But it generates the text of a thought process, which then guides subsequent predictions. The model conditions its outputs on its own generated logic.

More recently, models have been trained to recognize uncertainty, flag potential errors, and assess confidence. This remains shallow compared to human metacognition, but it represents a form of procedural self-monitoring. The model can now say “I am not certain about this” or “This reasoning seems flawed.”

The deeper question remains unresolved: can AI develop the ability to decide when to trust itself, when to seek clarification, and when to refuse a task? Current systems lack this autonomy. They exhibit scaffolded self-monitoring, not autonomous self-understanding.

Introspection was seen as a uniquely human capacity in 2016 requiring consciousness and self-awareness. The assumption held that statistical models could not examine their own processes. I did not anticipate that generating the text of self-reflection could be useful even without genuine introspection.

AI systems have no consciousness and no self-awareness

Status: Remains valid as stated.

This claim stands. Current AI systems show no evidence of subjective experience, phenomenal consciousness, or self-awareness. AI consciousness remains an open question in philosophy of mind, but the practical answer is clear: we have not created conscious machines, and we do not know how to do so intentionally.

The distinction matters: functional consciousness (behaving as if conscious) differs from phenomenal consciousness (having subjective experience). LLMs can produce human-like responses, but this does not imply inner experience. Passing behavioral tests like the Turing test does not prove consciousness—it proves behavioral indistinguishability.

AI systems lack the biological substrate and evolved instincts that underlie human consciousness. Self-awareness and survival drives would need to be explicitly programmed, not emergent. No current system has these properties.

Why we still believe it in 2025: Consciousness remains scientifically mysterious. We lack a definitive understanding of what generates subjective experience, making its replication in machines impossible to verify or achieve intentionally. The claim was correct in 2016 and remains correct today.

Today’s AI systems at best only appear intelligent, but are not truly intelligent

Status: Refuted as a meaningful distinction.

This was the philosophical anchor of the entire argument: machines might fool observers, but they lack genuine intelligence. The assumption rested on the Turing test critique—appearing intelligent differs from being intelligent.

What happened: “functional equivalence” made this distinction economically and organizationally irrelevant. From a systems perspective, what matters is capability, not inner experience. If a system performs novel tasks, adapts to context, transfers patterns across domains, and generates useful outputs, then for employers, markets, and workflows—the practical outcome is equivalent.

The adoption pattern followed predictably:

- “It’s not real intelligence”

- “It’s good enough”

- “Why would we not use it?”

The deeper issue: the claim assumed “true intelligence” had a clear definition. It does not. Intelligence manifests as behavior. If behavior is functionally equivalent, the distinction between “appearing” and “being” intelligent collapses for practical purposes.

The assumption in 2016 drew on a long philosophical tradition distinguishing appearance from reality. It felt intuitively correct that mimicry differs from genuine capability—mimicry had always been toy-like and produced no practical results. But what we called “mimicry” in 2016 turned out to be functionally equivalent to the real thing, and it delivers real value.

Summary

| Claim | 2025 Status |

|---|---|

| AI systems do not possess general, universal intelligence | ⚠️ Contested |

| AI systems cannot “understand” information | ❌ Refuted (operationally) |

| AI systems are not “creative” | ❌ Refuted (operationally) |

| AI systems lack introspection | ⚠️ Partially refuted |

| AI systems have no consciousness | ✓ Valid |

| AI systems only appear intelligent | ❌ Refuted (as meaningful distinction) |

In 2016, I correctly identified AI’s limitations, but I misjudged which absences would matter. I treated these philosophical distinctions as permanent barriers to capability, when they turned out to be irrelevant to practical impact. Systems that still lack consciousness and true general intelligence turned out to be far more capable and impactful than I expected.

And on that measure, the 2016 predictions underestimated what was coming.