The ‘Complex’ Perspective with Infographics

Almost 10 years ago I wrote “Die komplexe Perspektive” as a self learning experiment and minimal viable product (MVP) about the basic knowledge that I found to be necessary to understand the technological, societal and economic development. In an era defined by Big Data, AI, and rapid digitalization, the traditional mental models often failed us.

Ten years later, I am revisiting the book and illustrating its ideas with clear, modern infographics created using NotebookLM.

Chapter 1: Introduction

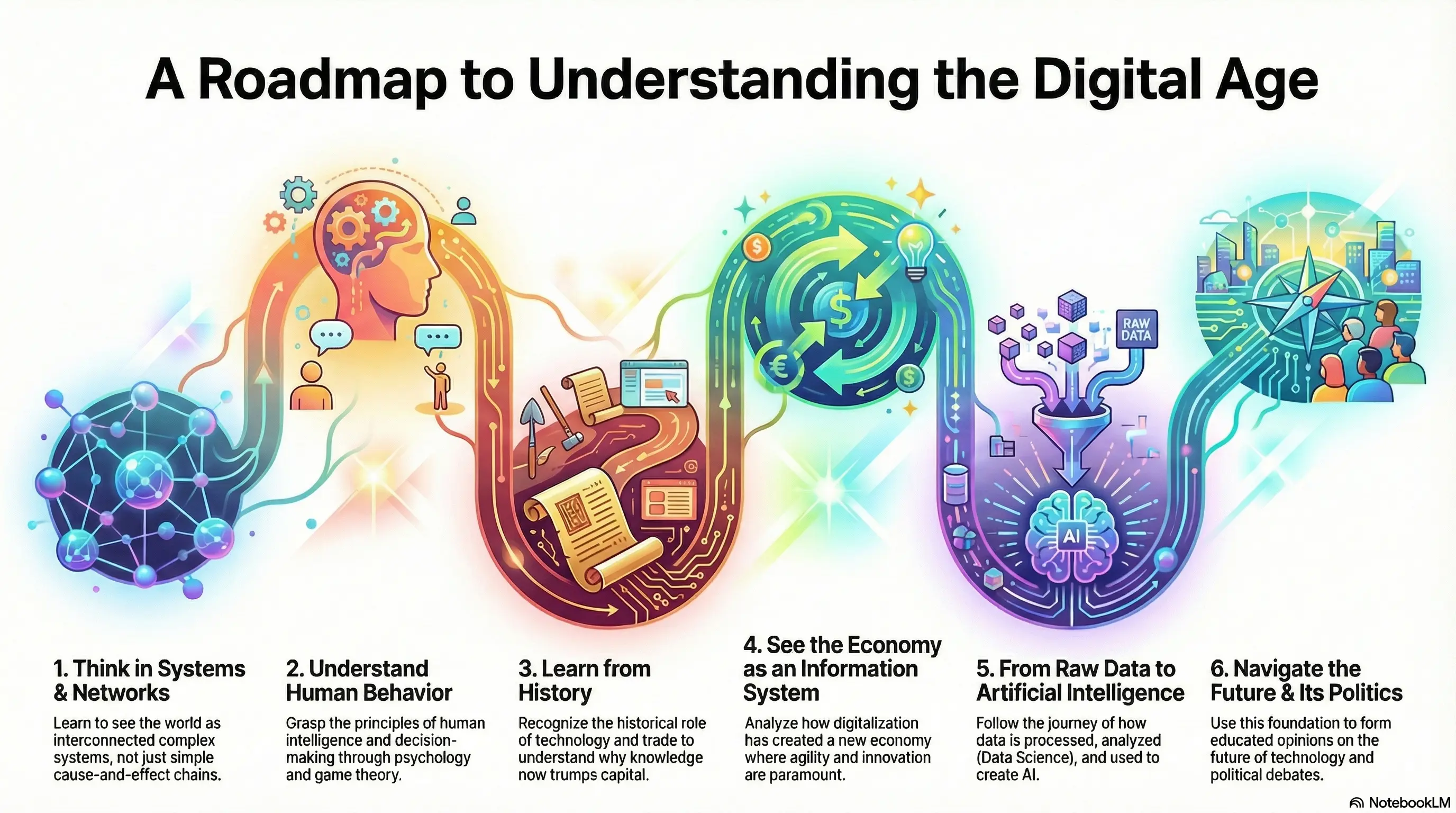

- Think in Systems & Networks The digital world consists of interconnected systems with feedback loops, not simple cause-and-effect chains. Understanding these networks is essential to grasp unintended consequences and emergent behavior.

- Understand Human Behavior Technology amplifies human strengths and weaknesses, including biases, incentives, and limited rationality. Psychology and game theory explain why people and organizations act the way they do in digital systems.

- Learn from History Technological change has always reshaped society, power, and economic structures. Looking at history reveals recurring patterns and explains why knowledge increasingly outweighs capital.

- See the Economy as an Information System Modern economies function through information flows, with prices, data, and signals coordinating decisions. Digitization accelerates these flows, making adaptability and innovation more important than size alone.

- From Raw Data to Artificial Intelligence Data becomes valuable only when processed and interpreted through data science and algorithms. Artificial intelligence is the result of this pipeline, not a mysterious or autonomous force.

- Navigate the Future & Its Politics Technological progress creates winners, losers, and conflicts of interest. Informed political and societal decisions require understanding both the technology and the complex systems it reshapes.

Chapter 2: Systems and Networks

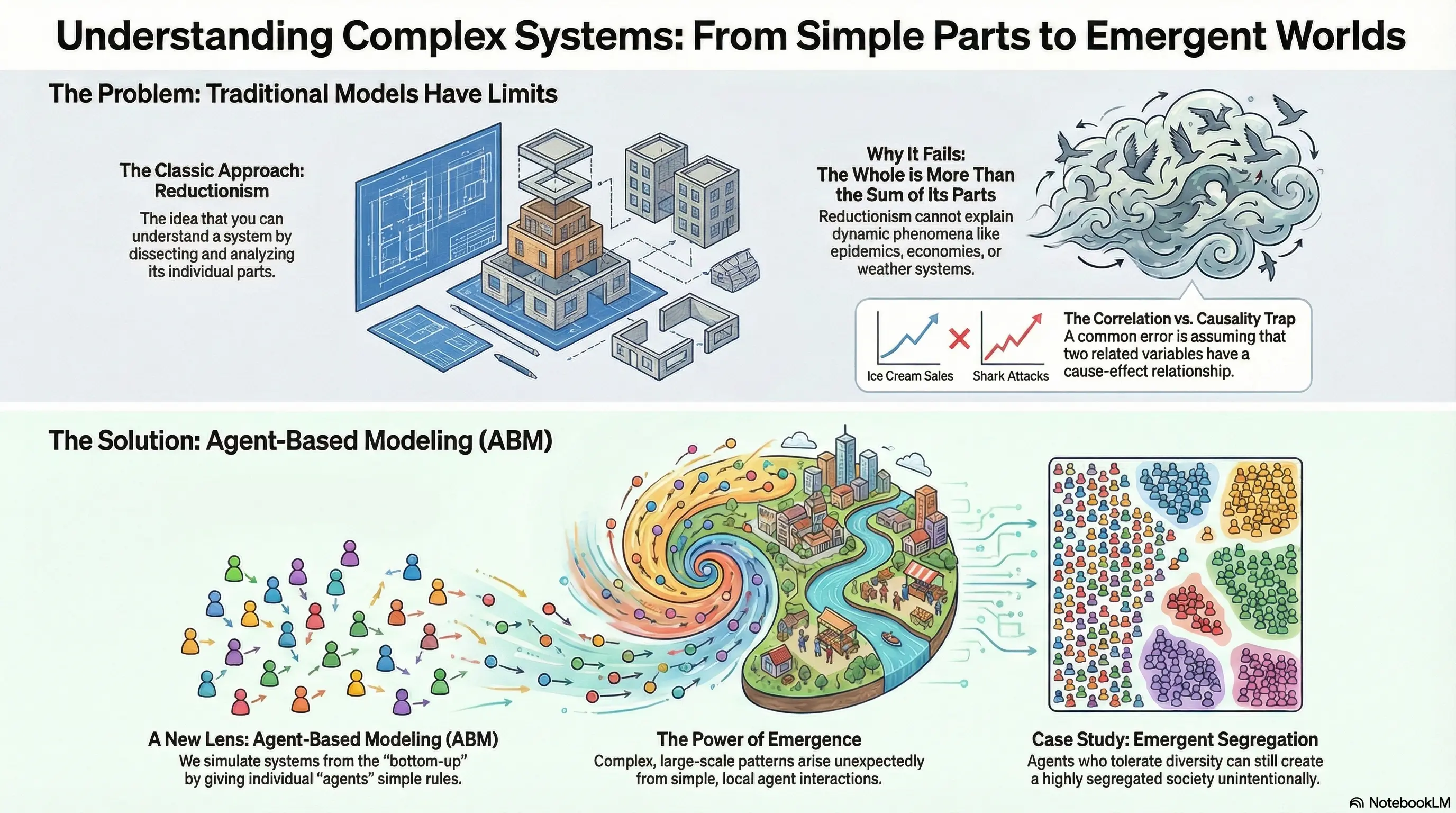

Traditional models approach the world through reductionism, assuming that a system can be understood by breaking it into parts and analyzing each in isolation. This works well for static or simple systems but fails for dynamic, interconnected ones where feedback loops and interactions dominate. In such systems, the whole exhibits behaviors that cannot be derived from individual components alone, and analysts often fall into the trap of mistaking correlation for causation.

Agent-based modeling offers a different approach by building systems from the bottom up. Individual agents follow simple local rules and interact with their environment and with each other. From these interactions, large-scale patterns and structures emerge that were never explicitly programmed. This makes it possible to understand how complex social, economic, or biological phenomena arise unintentionally from simple behavior.

Chapter 3: The Human Element

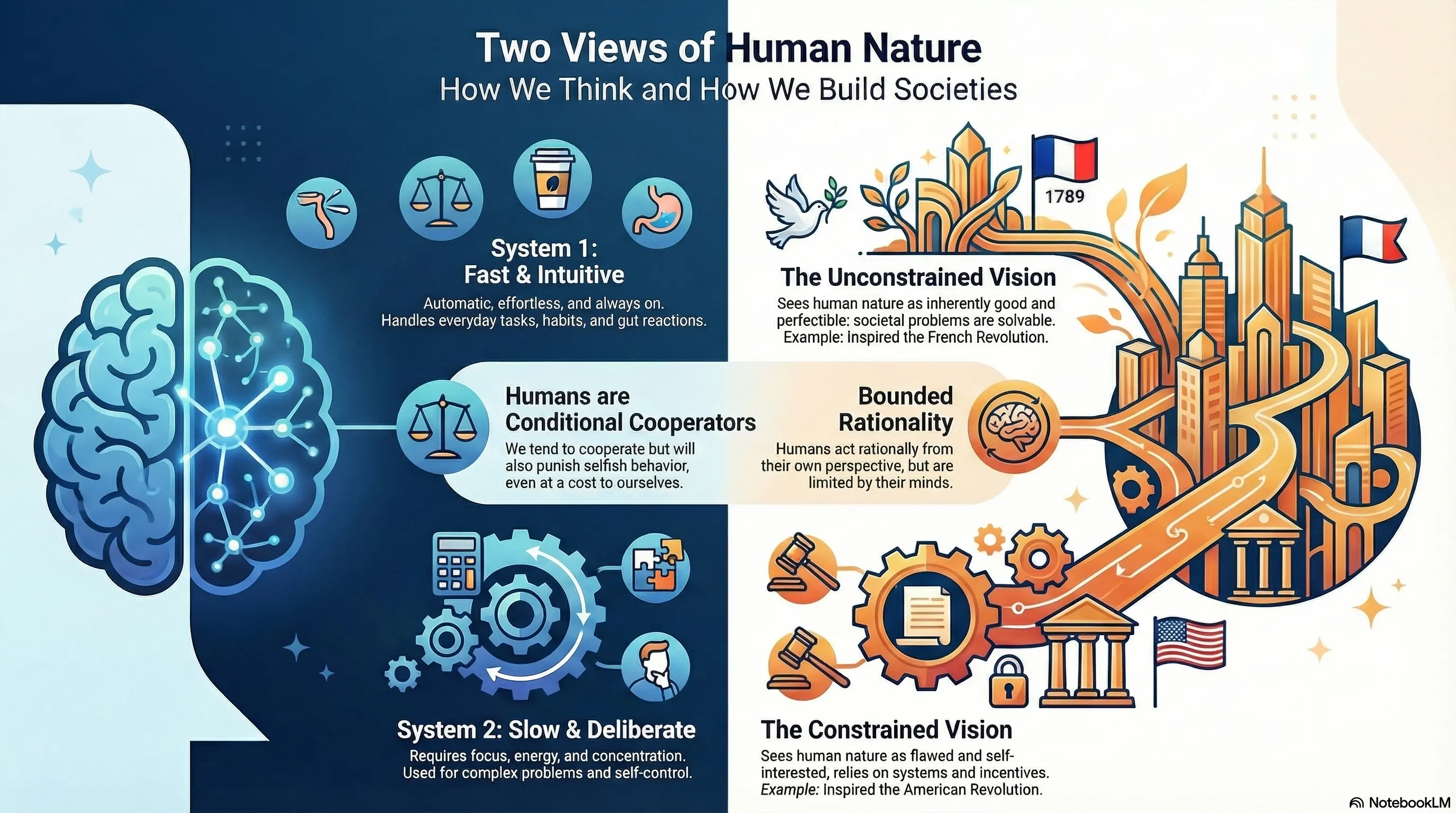

Human behavior can be understood through two complementary cognitive systems. One operates quickly and intuitively, handling habits, emotions, and everyday decisions with little effort, while the other works slowly and deliberately, requiring attention and energy to reason through complex problems and exercise self-control. Together, these systems explain why humans are neither perfectly rational nor purely impulsive, but adaptive decision-makers with clear cognitive limits.

These cognitive limits lead to bounded rationality: people generally act rationally from their own perspective, yet are constrained by limited information, time, and mental capacity. From this follow two broad views of human nature and society. One assumes humans are inherently good and society can be perfected through the right designs, while the other assumes humans are flawed and self-interested, requiring institutions, rules, and incentives to channel behavior productively. These contrasting views strongly shape how societies design laws, markets, and political systems.

Chapter 4: The Flow of History

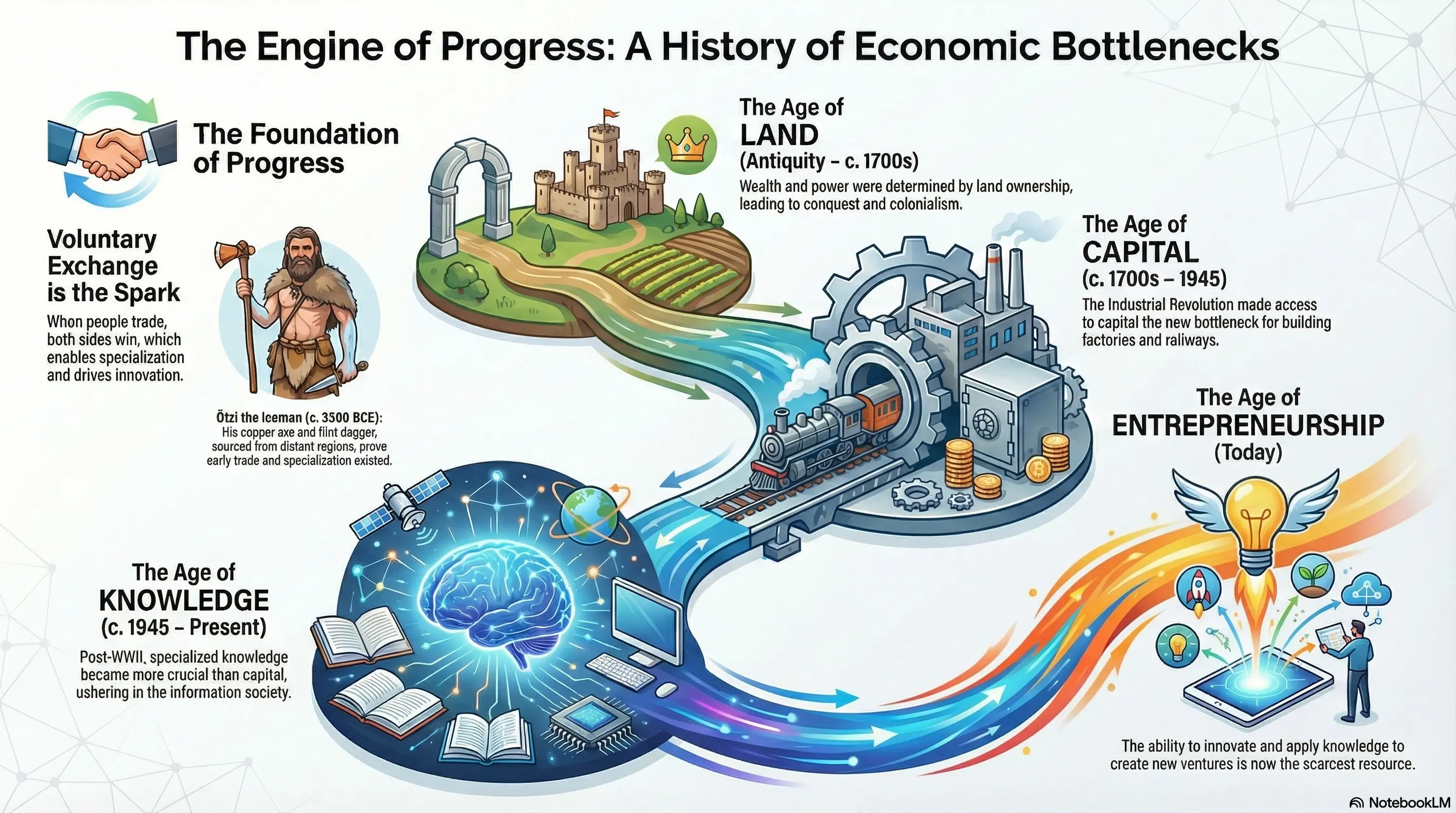

Economic progress can be understood as a sequence of shifting bottlenecks that determine what limits growth at a given time. Voluntary exchange is the constant foundation: trade enables specialization, cooperation, and innovation, and this mechanism has existed since the earliest human societies. In different historical phases, however, a single scarce resource dominated—first land, which defined power and wealth for centuries, and later capital, which became the key constraint during industrialization when factories, machines, and infrastructure required large upfront investment.

After the Second World War, knowledge replaced capital as the main limiting factor, as specialized expertise, education, and information became more decisive than physical assets. Today, the bottleneck has shifted again toward entrepreneurship: the ability to combine knowledge, technology, and opportunity into new products, services, and organizations. Progress continues not because resources disappear, but because societies repeatedly overcome one constraint and expose the next. This perspective explains why innovation, not accumulation alone, drives long-term economic development.

Chapter 5: Economies as Complex Systems

Traditional economics treats the economy as a predictable machine, inspired by classical physics and built on simplifying assumptions. It assumes rational, identical agents with perfect information and models markets as systems that naturally move toward equilibrium. Prices are outcomes of this mechanism, and deviations are treated as noise or temporary disturbances.

Complex economics replaces this machine metaphor with a view of the economy as an evolving network of interacting agents. Individuals and firms are adaptive, diverse, and fallible, and their local interactions generate system-level patterns that cannot be centrally designed or fully predicted. Prices function as real-time information signals that coordinate decentralized decisions under uncertainty. Markets are therefore better understood as evolving algorithms that continuously process information and adapt, rather than as systems seeking a fixed equilibrium.

Chapter 6: The Raw Material: Data

Data can be understood as a layered progression from raw facts to actionable insight. At the base are raw data as containers, which gain meaning only when organized into information and interpreted within context to become knowledge. Data appears in different structural forms—structured, semi-structured, and unstructured—each requiring different methods of storage, processing, and analysis. No single database technology fits all needs, which is why relational, graph, and NoSQL systems coexist within modern data architectures.

In practice, data flows through an ecosystem of operational systems such as CRM and ERP, which capture day-to-day activity, and into data warehouses that integrate these sources into a consistent view of reality. This integration enables enterprise-wide analysis and decision-making. At large scale, data is characterized by volume, variety, and velocity, which together define the challenges commonly labeled as “Big Data.” The central idea is that value does not lie in data itself, but in the ability to structure, connect, and interpret it effectively.

Chapter 7: Data Science: From Data to Knowledge

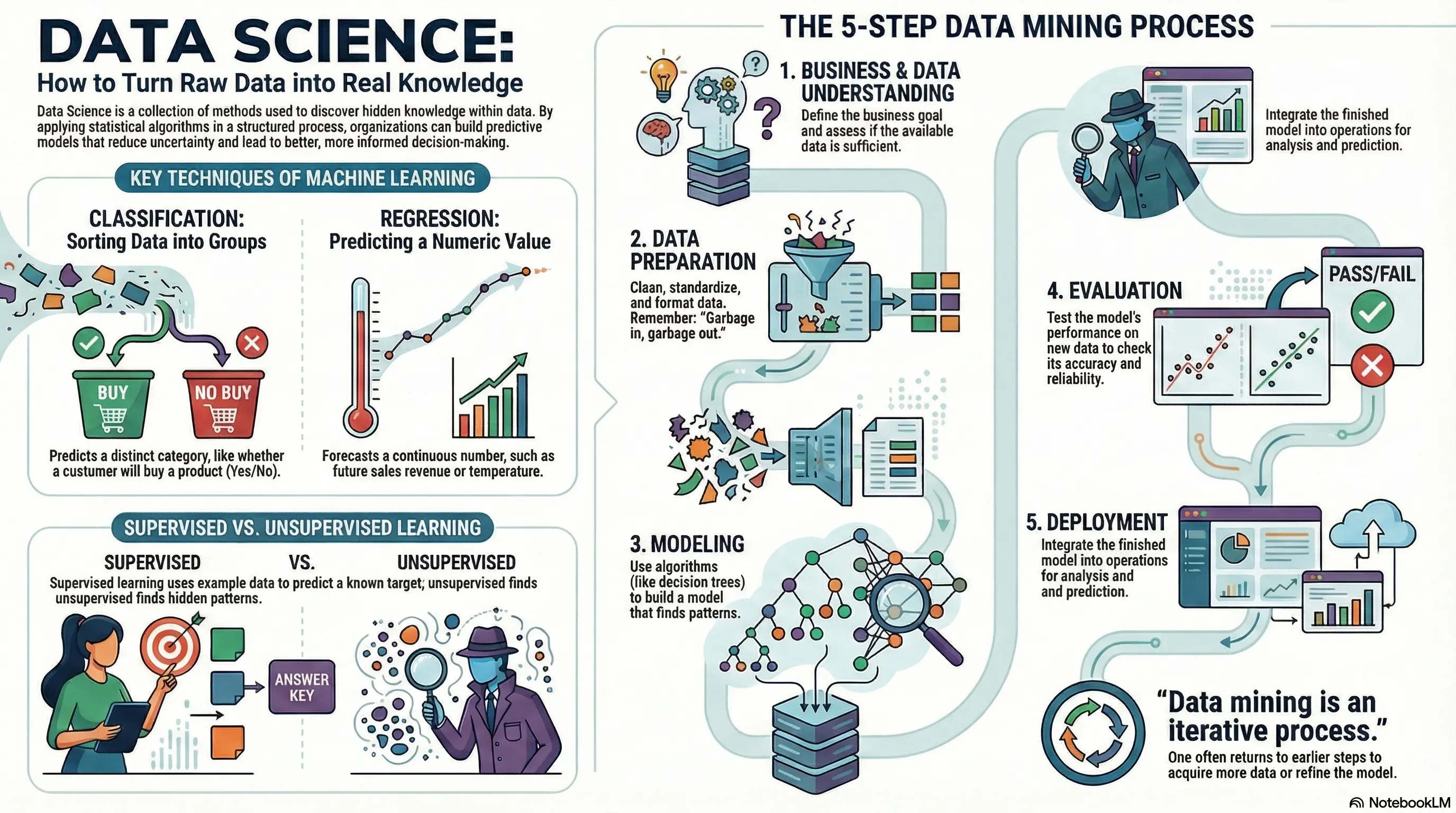

Data science describes how raw data is systematically transformed into usable knowledge that supports better decisions. Core techniques such as classification and regression allow models to sort observations into categories or predict continuous values, while supervised learning relies on labeled examples and unsupervised learning discovers hidden patterns without predefined answers. These methods reduce uncertainty by turning past data into probabilistic expectations about the future.

This work follows an iterative process that begins with clearly defining the business problem and understanding whether suitable data exists. The data must then be cleaned and prepared, since poor input inevitably leads to poor results. Models are built to detect patterns, evaluated on new data to test their reliability, and finally deployed into real-world operations. The process rarely runs only once; insights, errors, and changing conditions continuously feed back into earlier steps to refine both the data and the models.

Chapter 8: Artificial Intelligence

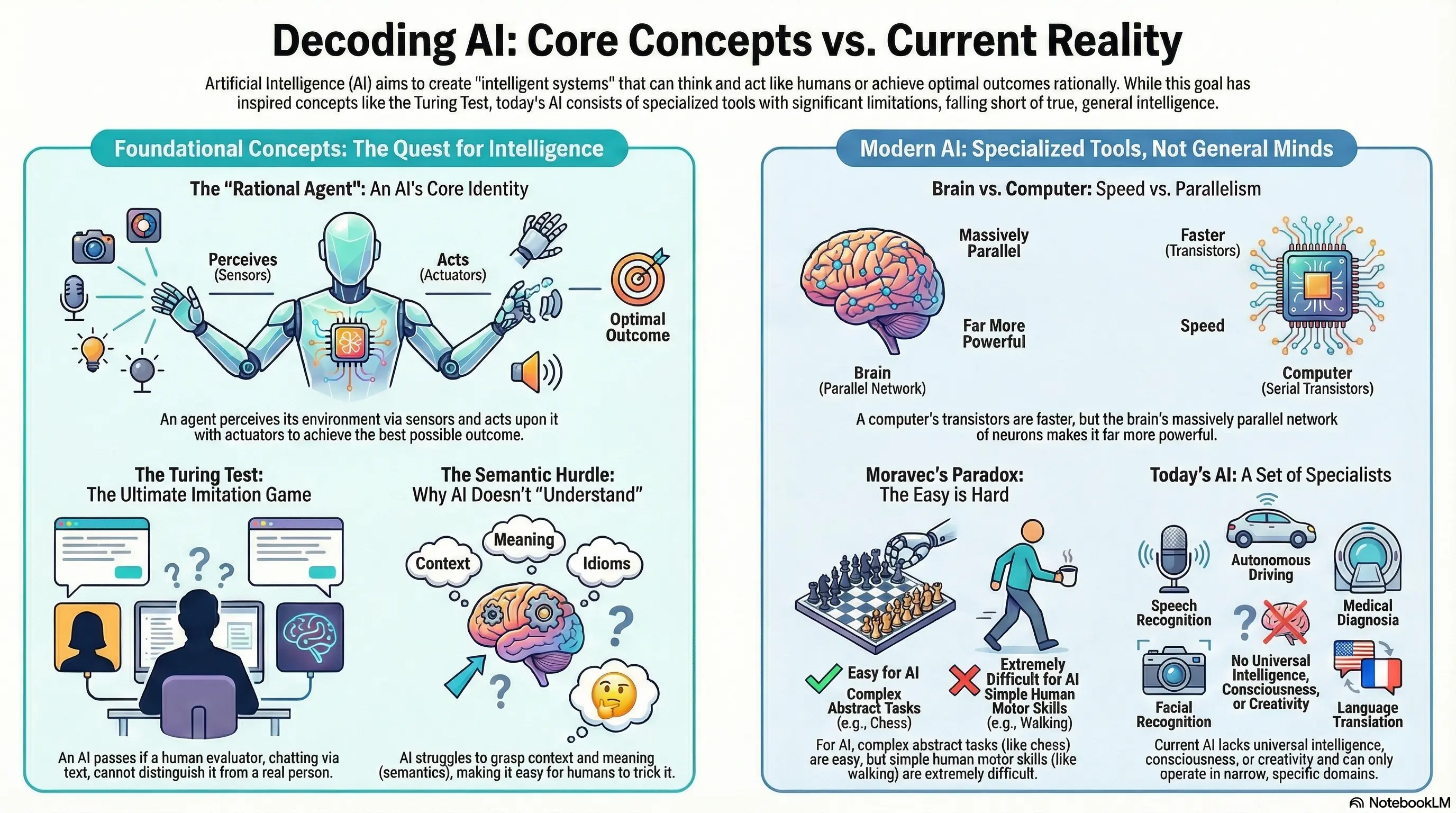

Artificial intelligence is best understood by separating its foundational ideas from its current reality. At its core, AI is defined through the concept of a rational agent: a system that perceives its environment through sensors, acts through actuators, and attempts to achieve optimal outcomes. Early benchmarks like the Turing Test focused on imitation rather than understanding, and AI still struggles with semantics—grasping meaning, context, and nuance rather than manipulating symbols convincingly.

Modern AI systems are powerful but narrow specialists rather than general intelligences. Computers excel at speed and precision, while the human brain remains vastly more capable through massive parallelism and contextual integration. This leads to Moravec’s paradox: tasks that feel intellectually hard to humans, such as abstract games, are easy for machines, while simple human skills like perception and movement remain difficult. As a result, today’s AI consists of domain-specific tools—speech recognition, image analysis, medical diagnosis—without general intelligence, consciousness, or creativity.

Chapter 9: The Digital Economy

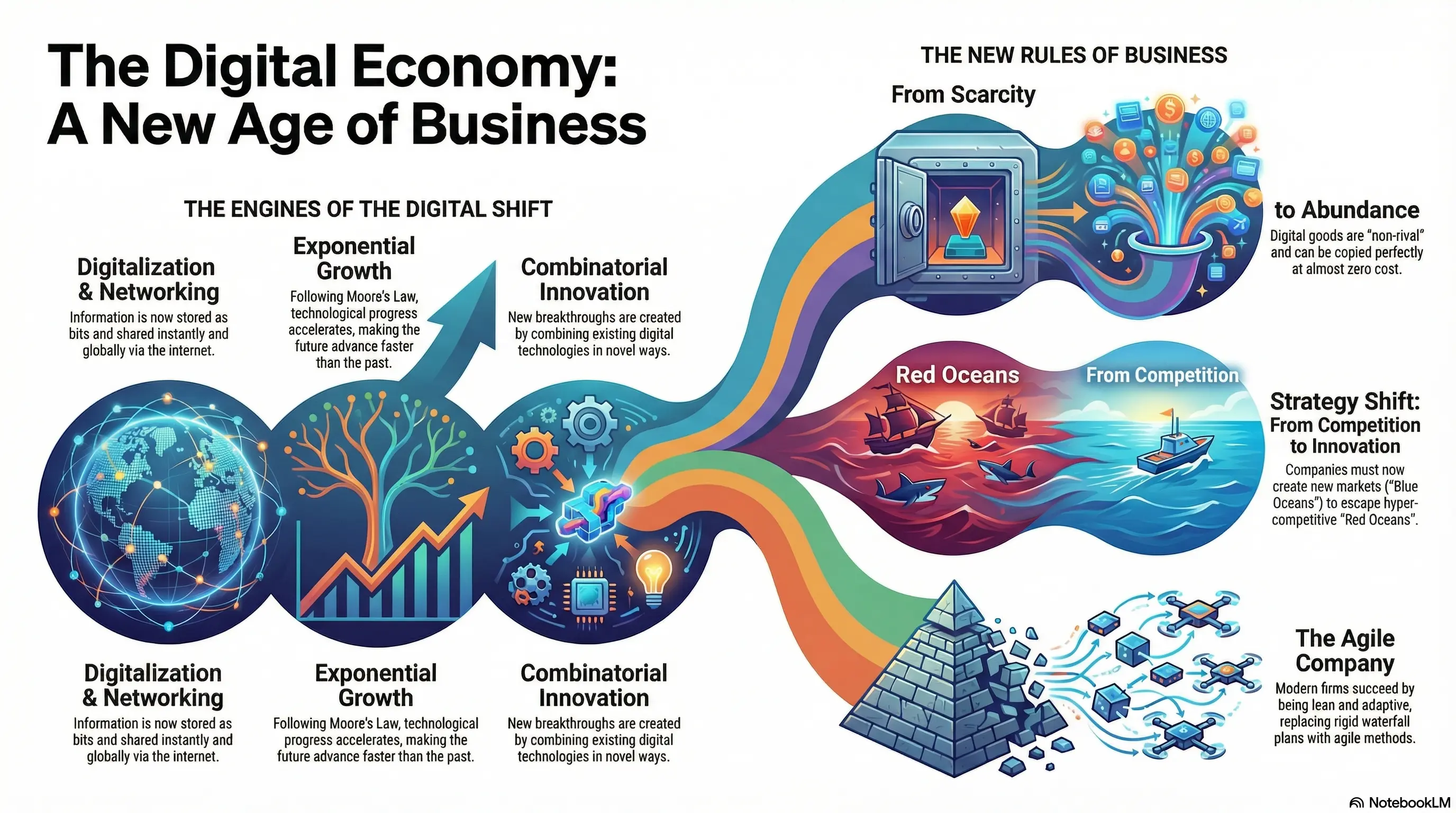

The digital economy represents a structural break from traditional business logic driven by digitization, networking, and exponential technological progress. Information is no longer tied to physical form, can be copied at near-zero cost, and spreads globally almost instantly, which accelerates innovation through the recombination of existing technologies. As a result, economic value shifts from managing scarcity to leveraging abundance.

This change rewrites the rules of competition. Instead of fighting in saturated, hyper-competitive markets, successful companies focus on innovation to create entirely new markets and business models. Speed, adaptability, and learning replace scale and long-term planning as the main sources of advantage. Organizations therefore evolve toward agile structures that can continuously experiment, respond to change, and turn technological possibilities into economic value.

Chapter 10: The Future

The future is shaped less by predictable trends and more by a small number of deep, interacting forces that operate within complex systems. Because societies adapt, learn, and change behavior, simple extrapolations of today’s data routinely fail, making long-term forecasting unreliable. Instead, understanding requires focusing on the structural drivers that reshape incentives, capabilities, and constraints.

One force is globalization and urbanization, which integrate billions of people into the global economy and concentrate economic activity in large metropolitan regions. A second force is demographic change, including aging populations and shifting workforce structures, which put pressure on productivity, social systems, and growth models. A third force is accelerating technological progress, driven by digitization, exponential improvement, and continuous innovation, producing disruptive capabilities rather than linear change. The fourth force is increasing connectivity, where networks of devices, systems, and people form a global nervous system that generates data and feedback at unprecedented scale.

Together, these forces enable a small set of technologies to have outsized economic impact. Advances in information technology, intelligent automation, robotics, energy systems, and life sciences interact and reinforce one another, amplifying their effects. The key insight is that disruption emerges not from single inventions, but from the combination of these forces operating simultaneously within a highly interconnected world.

Chapter 11: Politics in a Complex World

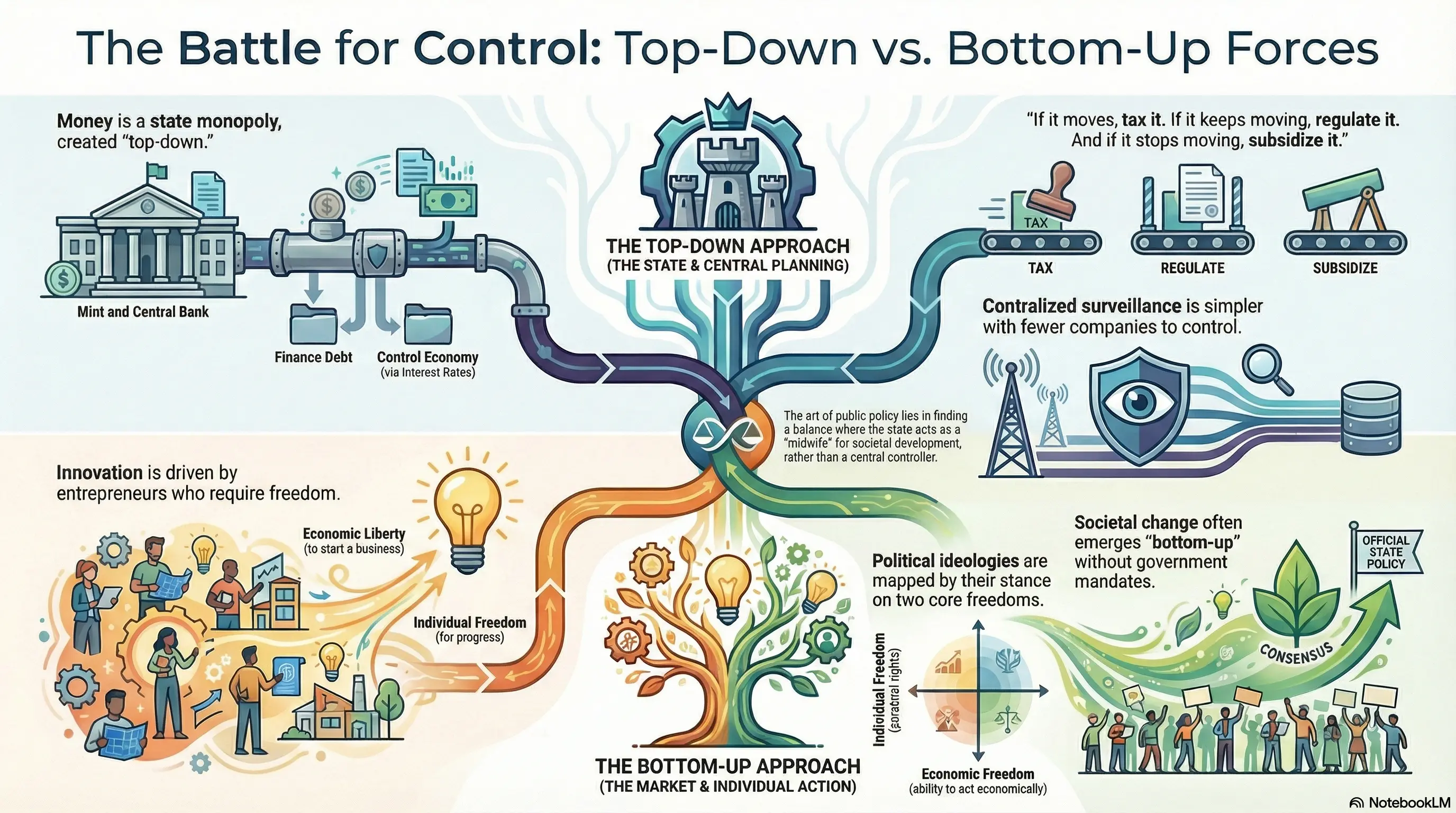

Economic and social systems can be shaped either through centralized control or through decentralized individual action. A top-down approach relies on the state and central institutions to create money, regulate markets, steer economic activity through taxation, subsidies, and interest rates, and maintain oversight through centralized control mechanisms. This model prioritizes coordination and stability but risks rigidity, information loss, and reduced adaptability in complex, fast-changing environments.

In contrast, bottom-up dynamics emerge from individual freedom, entrepreneurship, and voluntary cooperation. Innovation arises when people are free to experiment, start businesses, and respond to local information without central direction. Many societal changes—new technologies, cultural shifts, and economic transformations—develop organically before governments formalize or regulate them. The core tension lies in balancing these forces: effective policy neither fully suppresses bottom-up innovation nor abandons coordination entirely, but acts as an enabling framework rather than a commanding authority.

Chapter 12: Summary and Conclusion

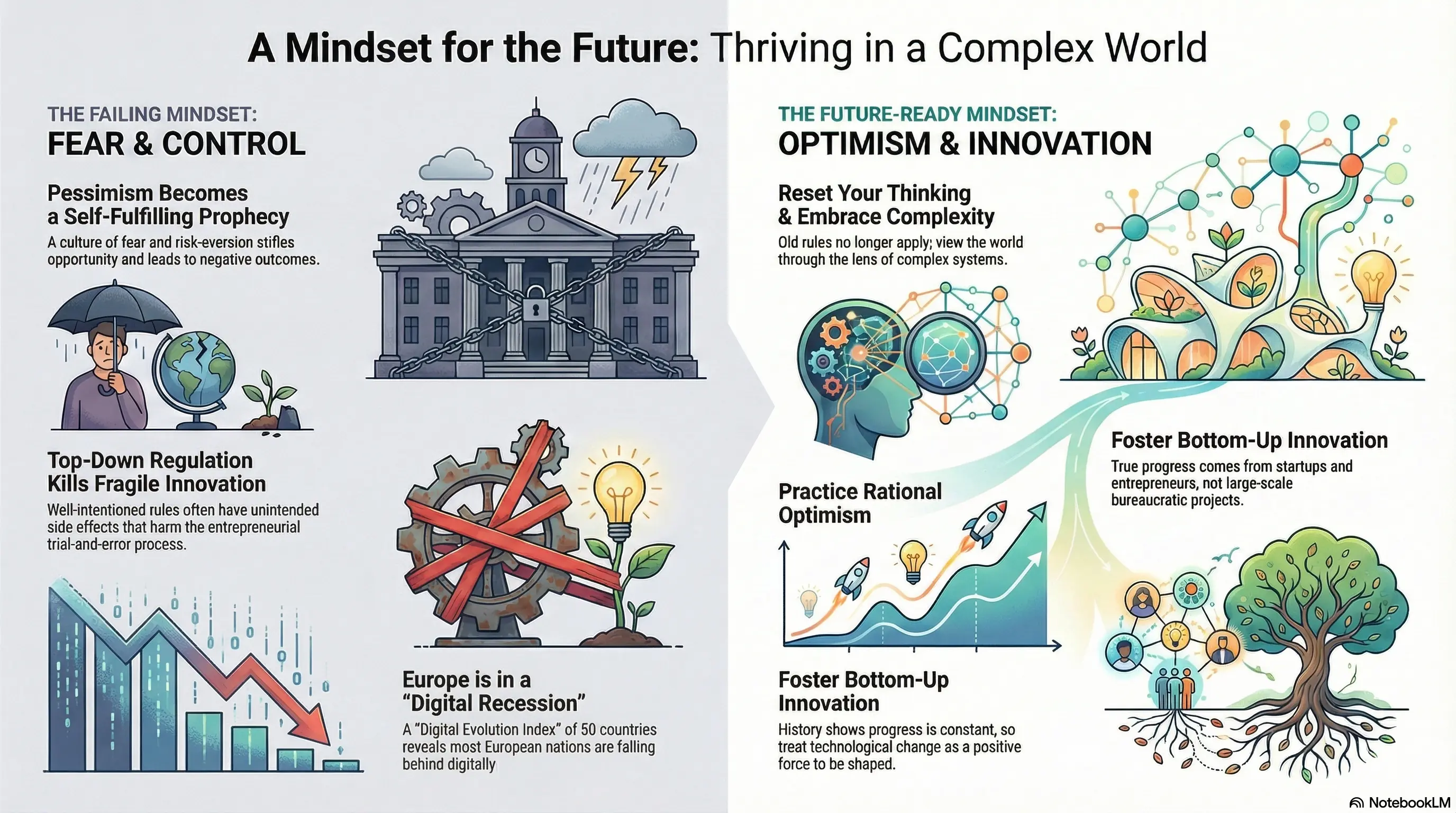

Thriving in a complex world requires a shift in mindset away from fear, pessimism, and excessive control. When societies focus on risk avoidance and top-down regulation, fear becomes self-reinforcing, innovation is stifled, and well-intended rules often produce fragile systems that cannot adapt. In such environments, pessimism turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to stagnation rather than safety.

A future-ready mindset replaces control with understanding and pessimism with rational optimism. It accepts complexity, abandons simplistic rules, and views progress as an emergent, bottom-up process driven by experimentation and learning. Innovation flourishes when individuals and entrepreneurs are empowered to explore new ideas, while institutions provide enabling frameworks rather than rigid constraints. The core message is that sustainable progress comes from embracing uncertainty, encouraging decentralized innovation, and cultivating optimism grounded in historical evidence rather than fear.