The Cellophane World

January 16, 2026

We are living in an age of effortless answers. This essay asks what happens to our voice, our empathy, and our sense of self when thinking becomes frictionless—and why some kinds of struggle may be worth keeping.

The Cellophane World

The question was small, a little splinter of idiosyncratic curiosity that usually acts as a low-burning ember for my day: I wanted to know why the scent of woodsmoke in late October feels less like a smell and more like a type of mourning. In another life, this would have been the start of a slow, messy journey. I would have let the thought rattle around in my brain like a stone in a pocket, feeling its edges, until I eventually found my way to a shelf or a conversation.

But this morning, before the thought could even fully form, the answer was there. It was elegant, fluent, and entirely devoid of the struggle that usually accompanies the “finding out.”

It feels, in these moments, as though a phantom hand has reached out to take the load. I have spent my life carrying a heavy rucksack of facts and figures, a cumbersome weight of dates, definitions, and the various “how-tos” of being a functioning adult. Then, suddenly, the straps are lifted. I feel lighter, certainly. But I find myself wondering if my gait is changing. I am beginning to realize that the weight wasn’t just a burden; it was a whetstone.

There is a difference, you see, between the mechanical labor we are right to shed—the scrubbing of floors or the long-hand division—and the constitutive friction that makes us who we are. The struggle to articulate a feeling is not a “bug” in the human operating system; it is the very process by which the soul is forged. Without that resistance, I am forgetting how to plant my feet. I am becoming a passenger in my own mind.

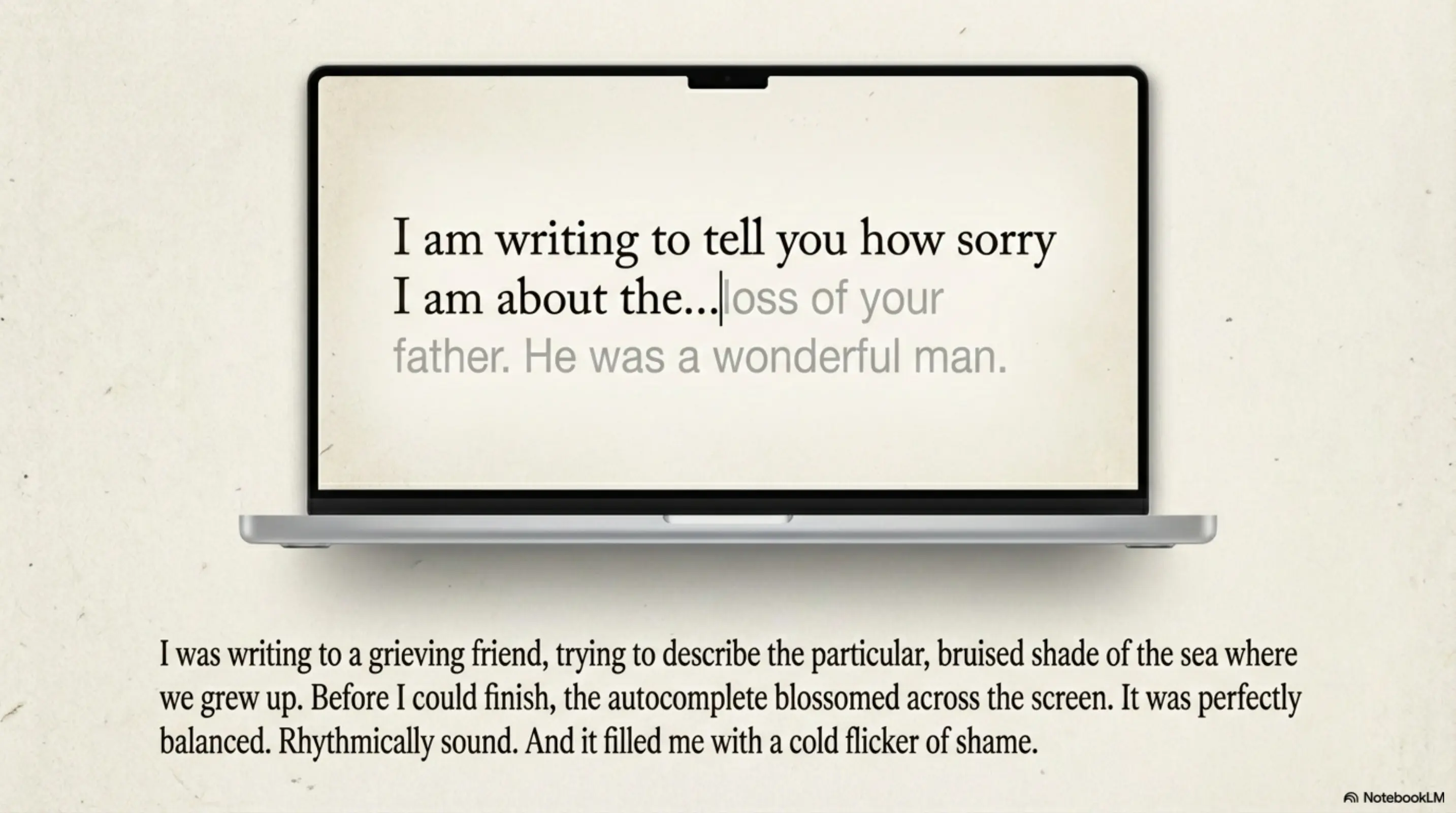

I felt this most acutely while typing a note to an old friend who is grieving. I wanted to say something about the particular, bruised shade of the sea where we grew up, something that might anchor him in our shared history. Before I could finish the sentence, the grey text of an autocomplete suggestion blossomed across the screen. It offered a phrase that was perfectly balanced and rhythmically sound. It was “right” in the way a plastic fruit is right—perfectly shaped, but providing only the satiety of a full stomach without the nutrition of a meal.

I stared at that ghost-sentence and felt a strange, cold flicker of shame. It wasn’t that the machine was wrong; it was that it had anticipated the “me” I hadn’t yet become. It had bypassed the labor of my empathy and offered a shortcut to a destination I hadn’t earned. Seeing that synthetic grace, my own words—stumbling, searching, clumsy—suddenly felt like a failure. It was as if the machine were suggesting a version of myself that was mathematically inevitable, yet personally absent. I felt a pang of redundancy, a fear that my very humanity was the only thing slowing the system down.

This is the “cellophane” of our new world. Truth is no longer a path I must hack through the brush; it is a finished product delivered to my door, shrink-wrapped for my convenience. But cellophane, while transparent and protective, creates a barrier. It prevents us from smelling the thing it covers. It preserves, yes, but it preserves through sterility. When the world is shrink-wrapped in these frictionless answers, I wonder what happens to the oxygen.

The machine operates on the “average”—the most likely word, the statistical mean of human experience. It can give me a generalized grief that sounds plausible to everyone but belongs to no one. We are witnessing a quiet war between Subjective Truth and Probabilistic Smoothness. The machine isn’t trying to be true; it is trying to be likely.

But to be an “I” is to be the statistical outlier. It is the gardener who knows the soil’s thirst not by a sensor, but by the specific, crumbly resistance of this earth against a thumb. That isn’t a data point; it’s a localized truth. We find ourselves in the deviation from the mean. When we offload the labor of thinking, we lose the scent of the garden. We trade the difficulty of the journey for the ease of the destination, forgetting that the journey was the thing that actually built the traveler.

I look at the autocomplete suggestion on my screen—that polished, polite ghost. My finger hovers over the backspace key. It would be so easy to just hit “tab,” to let the machine finish the thought and move on.

But we cannot simply go back to a world before the cellophane. The plastic is already wrapped tight around the globe. The challenge now isn’t just to delete the suggestion; it’s to develop a new kind of literacy—a literacy of resistance. We must learn to be the grit in the gears of our own efficiency. I want the clumsy word, the one that trips over its own feet but carries the true vibration of my own voice. I want to remain a creature of friction.

Because if we let go of everything that is difficult, what is left of the person who used to do the work? We might be lighter, but we will also be empty. The only way to remain whole in a vacuum-sealed world is to insist on the struggle, to seek out the places where the cellophane hasn’t yet touched, and to find the courage to be messy, honest, and entirely, stubbornly our own. I’m hitting backspace. I think I’d rather sweat for my sentences.

P.S. This text was written in multiple iterations with Gemini 3 Flash Preview, the images were generated with NotebookLM.