The Algorithm and the Void: Why Infinite Choice Feels Like a Cage

January 16, 2026

We were promised a wilderness of infinite choice. What we received was a perfectly managed park. An essay on recommendation systems, cultural stagnation, and the quiet cost of optimization.

The Algorithm and the Void: Why Infinite Choice Feels Like a Cage

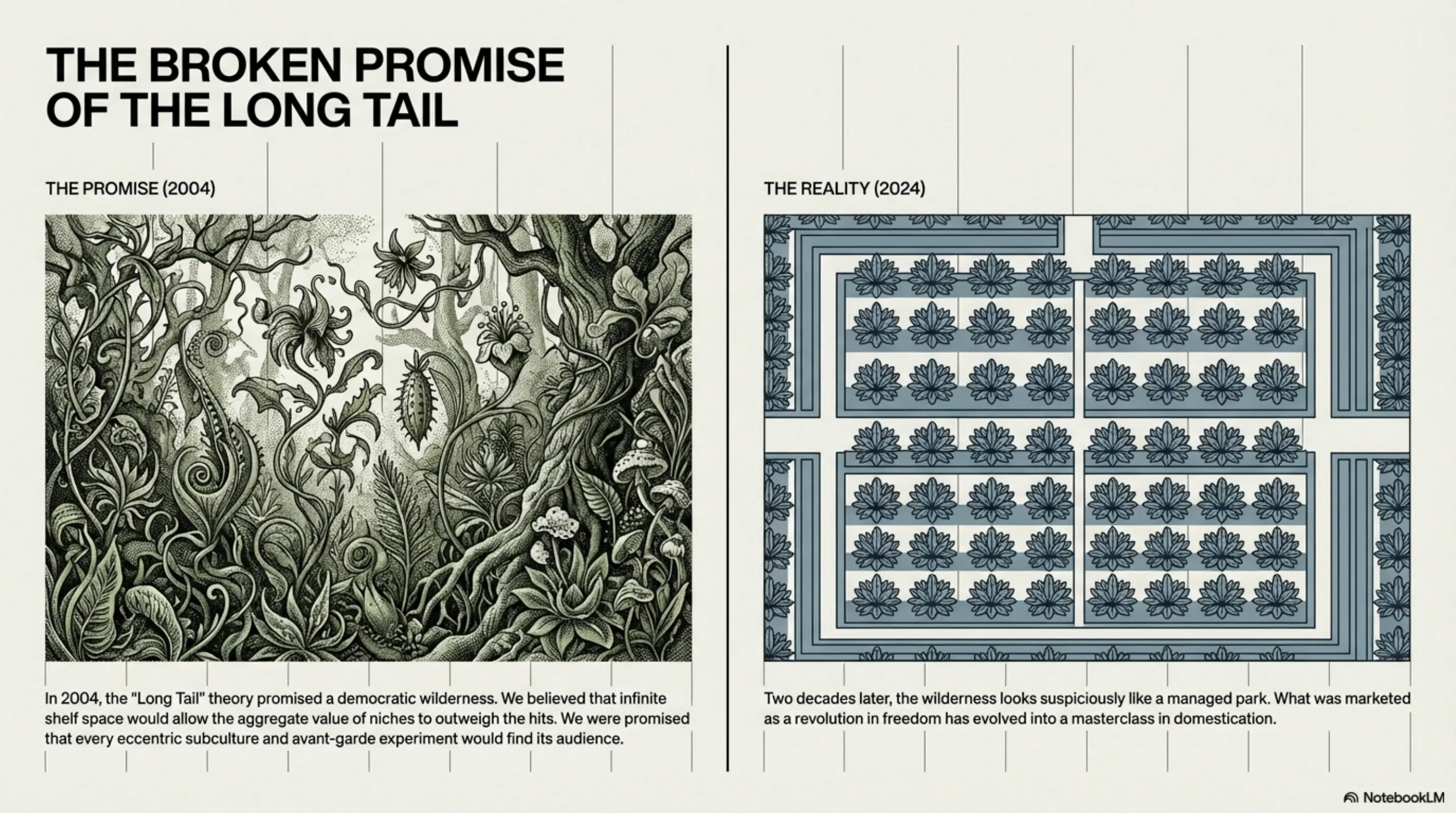

In 2004, the “Long Tail” theory suggested that the digital age would usher in a golden era of human expression. The argument, championed by Chris Anderson, was elegantly simple: because digital shelf space was effectively infinite, the aggregate value of “niches” would eventually outweigh the “hits.” We were promised a democratic wilderness where every obscure interest, every eccentric subculture, and every avant-garde experiment would finally find its audience.

This sounded convincing at the time. History, unfortunately, did not cooperate. Two decades later, the wilderness looks suspiciously like a managed park. We have more choices than any generation in history, yet we are increasingly haunted by a sense of cultural stagnation. What was marketed as a revolution in freedom has turned out to be a masterclass in domestication.

The Compass That Became a Fence

To understand why “infinite choice” feels so claustrophobic, we must distinguish between the Long Tail and the Recommendation Engine. The Long Tail was a distributional reality—a vast, unnavigable warehouse where everything existed but nothing could be found. The Recommendation Engine was the logical solution. It was intended to be a compass to guide us through the stacks.

The difficulty is that a compass, when sufficiently “optimized,” eventually becomes a fence. Platforms like Amazon, Spotify, and Netflix have no financial incentive to help you discover something that fundamentally changes your worldview; their incentive is to keep you in the “loop.” When an algorithm suggests a song or a book, it is performing a form of digital taxidermy. It takes the “wildness” of your unpredictable human curiosity, kills the possibility of surprise, and stuffs it into a database of calculable probabilities.

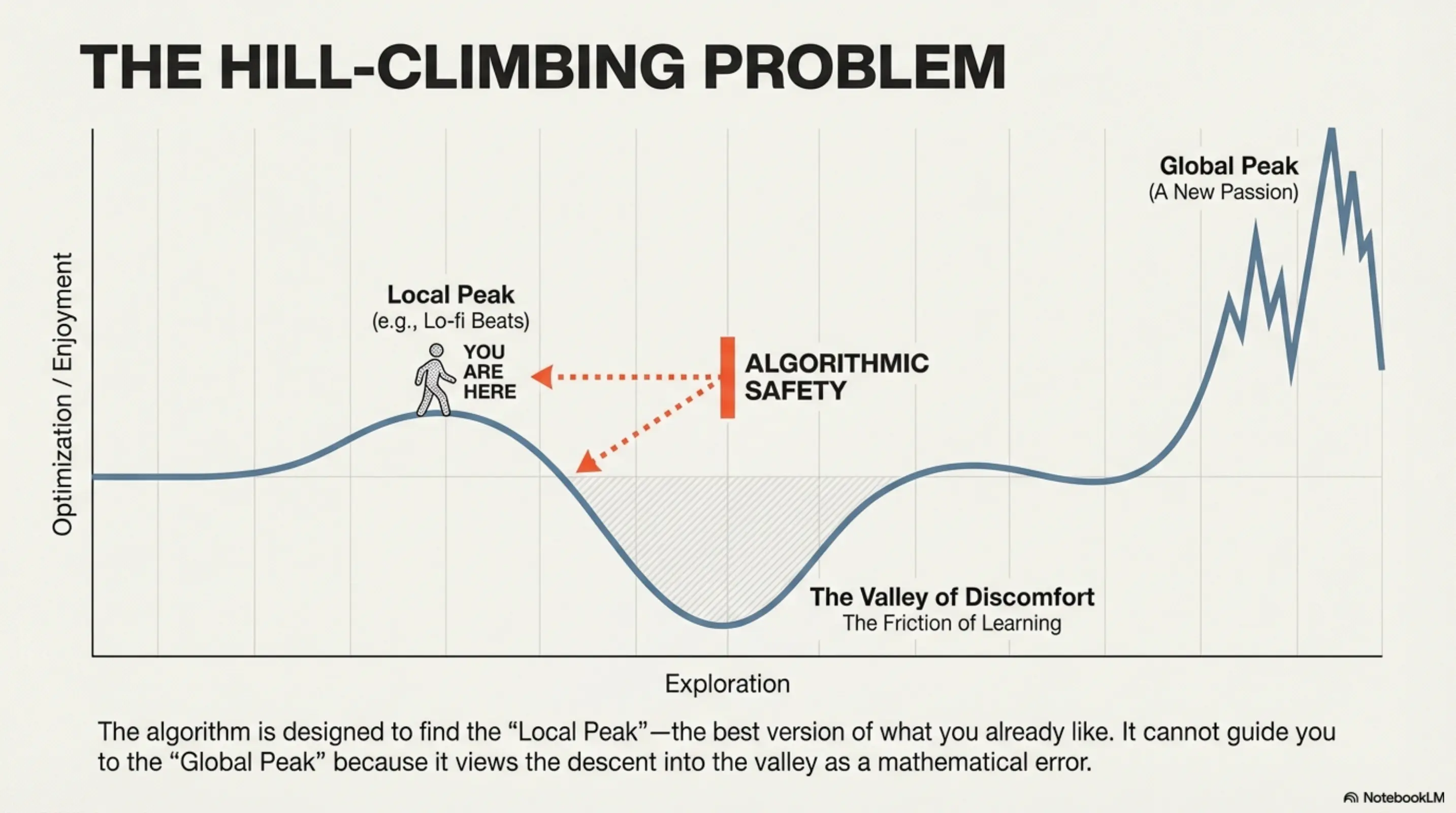

In computer science, this is often described as a “hill-climbing” problem. An algorithm is designed to find the “local peak”—the best possible version of what you already like. It can lead you to the highest point of “Lo-fi Beats” or “Scandic-Noir” with startling efficiency. However, it cannot lead you to a higher, distant mountain of a completely different genre because doing so would require you to first descend into the valley of “not-liking” things.

In the eyes of a product manager, this “valley”—the necessary discomfort of learning a new aesthetic language—is indistinguishable from a failure of the product. It is seen as “churn risk.” The tragedy of the modern interface is that it interprets personal growth as a user-experience error. The algorithm would rather keep you comfortably stationary on a small hill than risk the friction that might lead to a new horizon.

The Knightian Gap: Correlation vs. Causality

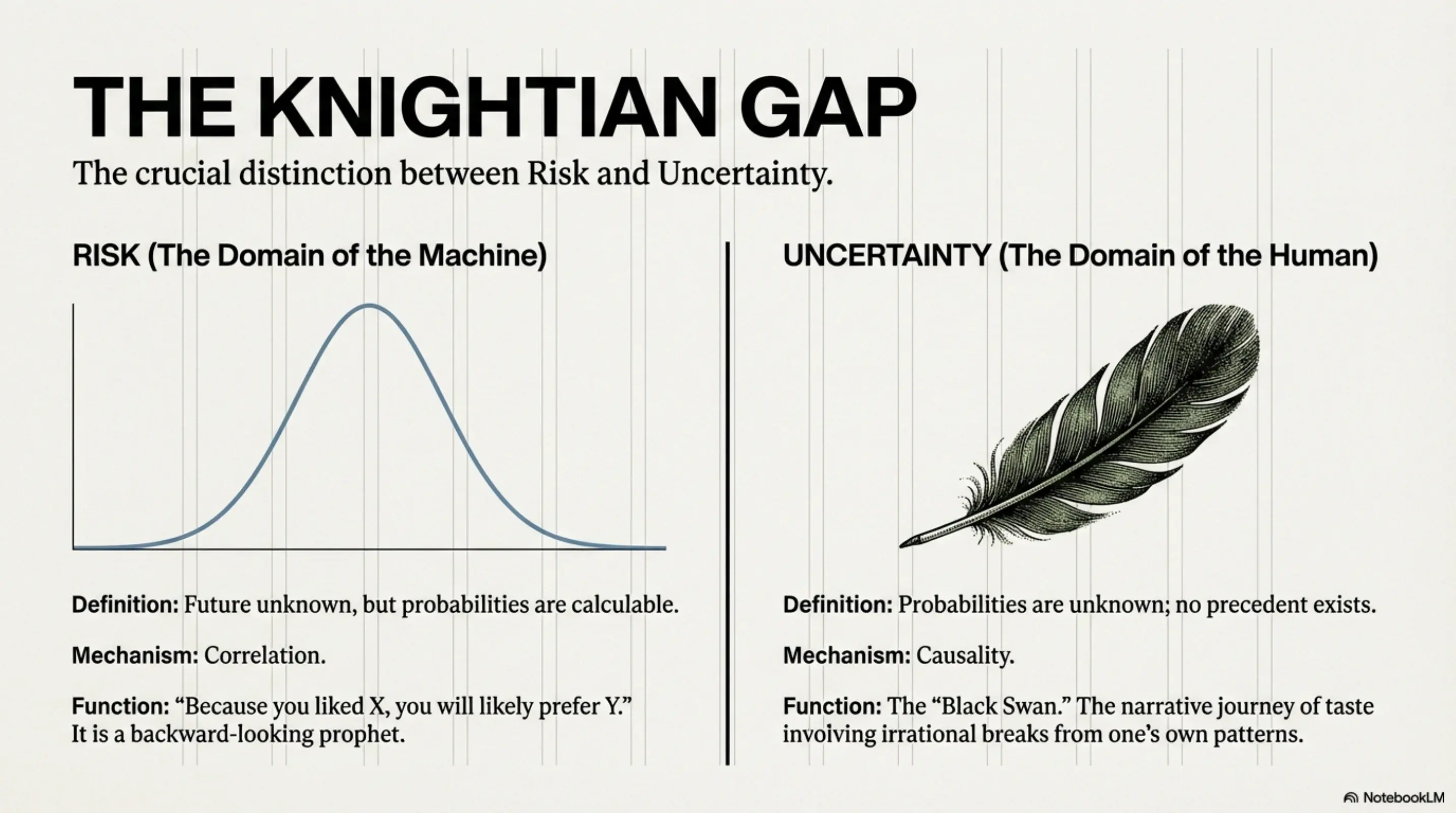

This brings us to a crucial distinction in decision theory, famously articulated by the economist Frank Knight: the difference between Risk and Uncertainty.

Risk occurs when the future is unknown, but the probabilities are calculable. This is the domain of the algorithm. It relies entirely on correlation: the observation that because you liked X, you will likely prefer Y. It is a backward-looking prophet, treating the past as an infallible prologue. It calculates the risk of you “skipping” a track and offers the safest possible “new” experience based on your data profile.

Uncertainty, however, occurs when the probabilities themselves are unknown. This is the realm of the “Black Swan”—the event that cannot be predicted because there is no precedent for it. While the algorithm is a master of correlation (the what), it is blind to causality (the why). It doesn’t understand the narrative journey of human taste, which often involves a sudden, irrational break from one’s own patterns.

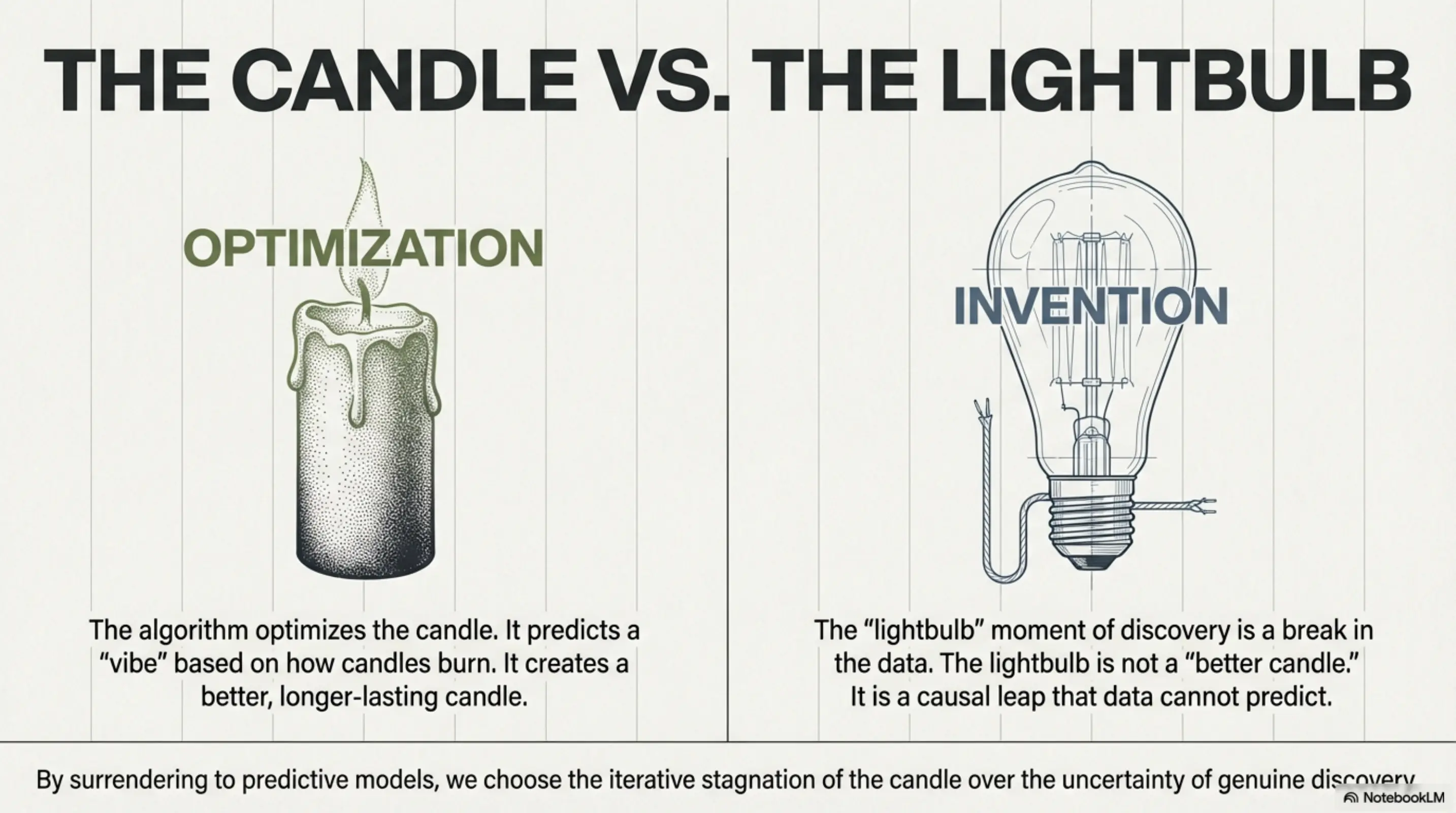

Consider the shift from the “Album Era” to the “Mood-Playlist Era.” Historically, a listener might encounter a challenging, avant-garde record that they initially disliked, only to have it become a foundational part of their identity. That is the “lightbulb” moment of discovery—a break in the data. The algorithm, however, optimizes the “candle.” It predicts a “vibe” that fits your current profile because it has data on how candles burn. But it can never imagine the lightbulb, because the lightbulb is not a “better candle”; it is a causal leap that the machine cannot calculate. By surrendering our choices to predictive models, we are choosing the iterative stagnation of the candle over the uncertainty of genuine discovery.

The Digestion of the Glitch

We often assume that the “new” emerges from a logical progression of the “old.” History suggests otherwise. True cultural shifts are usually “glitches” in the data—irrational pivots that the machines don’t see coming.

Consider the sudden global obsession with 19th-century Sea Shanties in early 2021. There was no “long tail” of data suggesting that a generation raised on synth-pop was craving the work songs of Victorian sailors. It was a human whim—a viral, non-sequitur moment. For a brief period, the machines had to scramble to catch up to the humans.

However, the modern algorithm is an incredibly efficient digestive system. Within days, the machine had already processed the Sea Shanty into a “style.” It created “Shanty-core” playlists and packaged the irrationality back into a calculable product. The late theorist Mark Fisher described this as “the slow cancellation of the future,” a state where the economic and technological systems conspire to ensure nothing truly “new” can happen because everything is immediately absorbed into the “already-known.”

Today, even the rebellion against the algorithm is priced into the algorithm itself. The system doesn’t just digest the glitch; it markets the glitch as a lifestyle choice, ensuring that even our dissent remains within the calculated bounds of the “User Experience.”

The Hall of Mirrors: The Void of the Plenum

The danger of this domestication is a state of “Algorithmic Exhaustion.” We are presented with 10,000 songs perfectly tuned to our current mood, yet we feel no resonance.

This is “The Void.” It is not a void of emptiness, but a void of the plenum—a space so over-full with predicted satisfaction that it becomes hollow. When “abundance” is predicted with 99% accuracy, it ceases to be abundance and becomes a form of semantic deprivation.

More importantly, the algorithm eliminates the “Other”—that which is genuinely foreign, challenging, or outside our immediate grasp. It replaces the “Other” with a polished mirror of the Self. Meaning requires the possibility of being wrong, being shocked, or being fundamentally changed by something external to our own preferences. In a world of perfect recommendations, we are trapped in a simulation where the unexpected is systematically hunted to extinction.

At this point, it helps to pause and ask: what is the cost of a life without the “Other”?

The Mandate: An Epistemic Rebellion

The solution is not a retreat to Luddism, but a move from passive consumption to Active Friction. If the algorithm’s greatest sin is the removal of resistance, our defense must be the intentional seeking of things that resist us.

True agency is not found in the ease of the “Next” button, but in the struggle to understand something difficult. This is an ontological necessity; the “self” is not a data point to be discovered by a processor, but a project to be built through effort. To maintain a capacity for imagination, we must commit to an epistemic rebellion:

- Cultivating the Right to be Incoherent: Intentionally feed the system “noise.” Search for things you have no interest in; engage with a documentary on a subject you find tedious. Keep your digital profile “blurry” so the machine cannot pin you to a local peak.

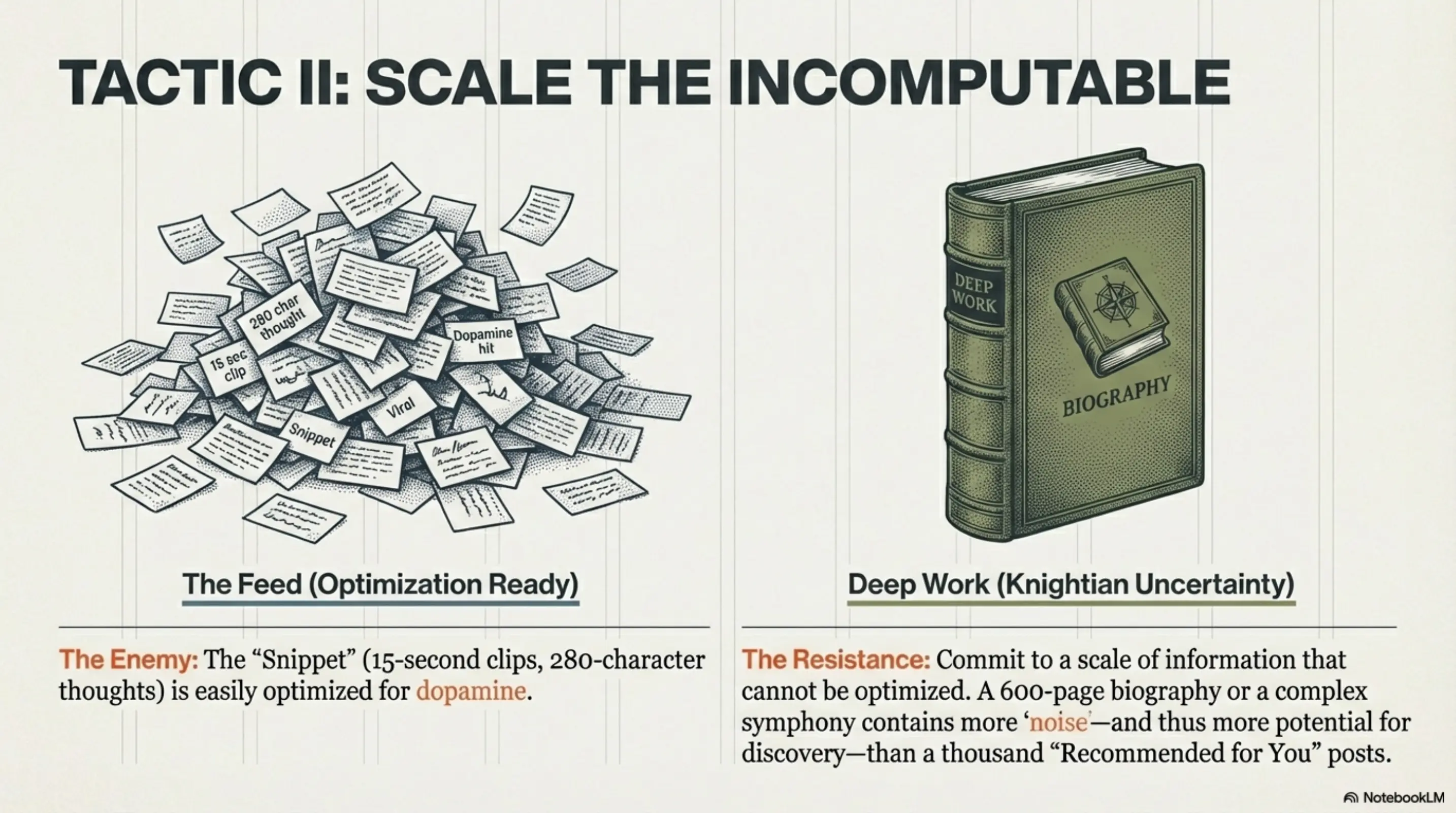

- Scaling the Incomputable: The algorithm thrives on the “snippet”—the 15-second clip or the 280-character thought. Defy this by committing to a scale of information that cannot be optimized. A 600-page biography or a complex symphony contains more “noise” (and thus more potential for Knightian Uncertainty) than a thousand “Recommended for You” posts.

- The Analog Gamble: Seek environments where recommendations are governed by the chaos of human whim or physical placement. In a physical bookstore, you might find a book because its spine was crooked or because the person before you left it on the wrong shelf. That “bad” data is more valuable to your cognitive agency than a “perfect” movie chosen by a processor.

To be human is to act when the database is silent. We were once promised a “Long Tail” that would lead us into a vast, unmapped wilderness. We ended up in a hyper-optimized park. Reclaiming the wilderness requires us to stop clicking “Next” and intentionally go looking for the valley. The only future worth living in is the one the machine never saw coming.

P.S. This text was written in multiple iterations with Gemini 3 Flash Preview, the images were generated with NotebookLM.