Are we there yet? Can AI produce art? Part #2

December 01, 2025

I really enjoyed working on the first story, so I tried again — this time also generating images with Google’s Nano Banana Pro.

What I like most about this new piece is the setup: a woman who has tried everything, no one believes her anymore, and in desperation she seeks out a PI. It’s such a clean, classic way to kick off a noir story.

Hardboiled Stakes - Lucy Westenra

The first time I saw Lucy Westenra she was pressed up against the night like it was a plate-glass window and she was dying to get in.

She stood on the curb under the yellow eye of a streetlamp, swaddled in white fur that had never met the animal it came from. The rain came down cold and thin, like it was ashamed to be seen in this part of town. Her taxi had just pulled away, spitting exhaust and bad manners, and she was left there with her valise, a long pale figure cut out of the dark, all silk lines and expensive worry.

The city hummed behind her—bars, neon, and the kind of music you only hear through walls, where the trumpet sounds like a consolation prize. I was supposed to be going home. That’s the fun thing about supposing.

She spotted my doorway the way a drowning girl spots driftwood. My office was up a flight of stairs that hadn’t been swept since the Spanish-American War, marked only by a frosted-glass panel that said:

NATHAN CROW

INVESTIGATIONS

DISCRETION A SPECIALTY

The “DISCRETION” part was half peeled off, which made it more honest than most things in this city.

She hesitated, and then she came in.

She was even more beautiful up close. Not the cheap kind that smells like perfume and bad decisions. The trained kind—the kind money teaches. Pale, too pale, like she’d been living underwater. The fur slid off her shoulders when she sat down, and underneath was a dress the color of old blood on black satin. Her hair was a soft, tangled gold, like money that’d been through too many hands.

“Mr. Crow?” she said, voice low and polished in a way that made me suddenly remember I owned a tie and never wore it.

“That’s what it says on the door,” I told her. “Unless it fell off in the middle of the night.”

She tried to smile. It didn’t get anywhere near her eyes. “They told me you’re good at finding things.”

“Things, people, bad habits. Depends how much they want to be found.” I watched her face. It was the kind of face people lie to. “What do you want to find, Miss—?”

“Westenra,” she said. The name sat in the room like a perfume bottle on a cheap table. “Lucy Westenra.”

The name said ships and drawing rooms and long dinners with the wrong sort of wine. It didn’t belong in my office with its cracked walls and cheap calendar girls.

“Well, Miss Westenra,” I said, “what’s gone missing?”

Her hand fluttered at her throat. There was a thin strip of silk tied there, black as a priest’s secret.

“I want you to find out who’s going to kill me,” she said.

Whisky has a lot of interesting effects on a man, but it doesn’t usually make him hear that kind of thing.

“Lady,” I said, “that’s one step ahead of my usual line of work. I find the guy after he’s done the job.”

“They’ve tried three times already,” she said softly. “They keep failing. But they’re getting closer. I can feel it.”

“You go to the police?” I asked.

Her laugh was small and bitter. “The police think I need ‘rest.’ And the doctors agree. Women like me,” she added, with a little twist in her lip, like the taste of the words was bad, “are always taking things too seriously, you know. That’s what they say.”

“I’ve heard they say a lot of things,” I said. “Where you staying?”

“The Westenra. It’s my family’s hotel.” She watched my eyes; I tried not to give her what she was looking for, but she saw it anyway. “Yes. Those Westenras. You’ve heard of us?”

“Hard not to. Marble lobby, string quartet, and prices that make grown men cry.”

Her fingers tightened on the handle of her handbag. “There’s been… an incident. They’re calling it an ‘attack.’ The papers say I was ‘set upon’ by a stranger in my sleep. To make it sound sordid and interesting, I suppose. It was nothing like that.”

“What was it?”

She looked at the door the way people do when they want to make sure the world is still locked outside.

“It happened three nights ago. I woke up feeling… drained. Weak. Like I’d run for miles in my sleep. There were marks on my throat.” Her hand slipped again to the black silk. “Just above the pulse. Two small wounds. Very precise. No tearing. The doctor said it was… a bite.” She swallowed. “He suggested a rodent.”

“Rodent?” I said. “What kind of rat stands on two legs and knows surgery?”

“He doesn’t believe me,” she said simply. “None of them do. But I know what I felt. Something in the room. Over me. On me. Cold, but… pressing. I couldn’t move. Couldn’t cry out. It seemed to go on forever. And when I could finally scream, the thing was gone and the window was open and—”

Her voice tangled. She bit it off.

“And then the lock was open and nobody could explain it,” I said. “I read the morning rag.”

“You think it’s all nonsense,” she said. “Like everyone else.”

“I think I’ve seen enough nonsense in my time to give it a chair and let it talk.” I leaned back. My springs complained. “Who’d want you dead, Miss Westenra?”

Her gaze flattened. “Everyone, if you believe the gossip columns. Money does that, Mr. Crow. Money and parents who think a daughter is just a way to give it to the right man.”

“Let’s narrow it down from ‘everyone’ to the ones with enough push to hire someone with teeth.” I lit a cigarette. She watched the match flare like she wanted to dive into it. “Family?”

“My mother’s in Switzerland with her nerves,” Lucy said. “My father’s… gone.”

“Gone how?”

“As in dead. As in a year ago. He left me the majority of the estate.” Her mouth twisted. “My mother was… disappointed.”

“You live alone?” I asked.

“Not precisely. There’s my cousin Arthur—he’s technically a Lord of something or other, but you’d never know it. He manages the hotel, more or less. And there’s Quincy, an American—old friend of the family. And Dr. Seward. He—”

She stopped. Just the name did something to her shoulders, pulled them tight like a corset string.

“Dr. Seward?” I prodded.

“He’s… devoted,” she said. “My doctor, among other things. They’re all staying at the hotel. They all say they’re concerned.” She laughed again, with no humor in it. “Three men and my mother’s lawyer, and not one of them believes me. But they all insist I’m not to be left alone.”

“You’re very much left alone right now,” I noted.

“That’s because they’re meeting with another specialist. A Professor Van Helsing. Continental. Famous for saying strange things in Latin. They think if they sit him down with enough port and talk about my ‘hysteria,’ he might have a new trick for keeping me quiet.”

“In other words,” I said, “you slipped the leash.”

“For the moment.” She leaned toward me, eyes shining in the shadowed room. “Mr. Crow, I don’t care if you think I’m mad. I only care that you look. That you watch. I don’t trust any of them now. Not entirely. Not after what’s happened.”

“You got the money?” I asked. I don’t dance unless the band’s been paid.

She took out an envelope and slid it across my desk. It made a satisfying shush on the scarred wood. I thumbed it. Enough twenties to make my landlord think I’d turned honest.

“You get me killed,” I said, “this is only the down payment.”

Her smile flashed—a real one this time, brief and crooked. “You’ll come to the hotel?”

“I’ll come,” I said. “And I’ll watch your back.”

“It’s my throat you should be watching,” she said softly. Then she stood, scooped up her fur, and was gone, leaving a trail of expensive perfume and desperate fear.

The Westenra Hotel sat on the good side of town and looked down its marble nose at the rest of us. Crystal chandeliers, floors you could eat off if you could afford the tip, and bellboys who wore more brass than a Sunday-band cornet.

They didn’t want to let me in, not the way I was dressed. My suit had seen better days, and more of them than it cared to remember. But Lucy was waiting just inside the rotating door, pale as the moon and twice as far away. One look at her and the doorman melted. Money talks. It doesn’t always say nice things, but people listen.

We rode up in a gold-plated elevator that hummed like a frightened bee. Her suite was on the top floor—three rooms, two bathrooms, and more velvet than a whorehouse on payday. Windows high and fastened, heavy curtains, a bed big enough to bury your troubles in.

“These locks,” I said, checking the brass. “They the same since the last visit from Mr. Rodent?”

“Yes.” She watched me. The room made her look smaller, like a girl playing dress-up in the world’s coffin.

“The doctor see the marks?” I asked.

“Dr. Seward sees everything,” she said. “He writes it all down in his little books. Times, dates, what I say, what I eat, how often I scream in the night. I feel like a specimen in one of those jars he keeps.”

“Jars?”

“In his office on the second floor. The sanatorium wing.” She walked to the window, tugged the heavy curtain back. The city lay below, all lit up and humming. “My father liked to keep every part of the business close to the chest. Even the madmen.”

“You’re saying there’s a loony bin in this hotel?”

“Clinic,” she corrected, with a faint smile. “For the nervous and the wealthy. Fewer bars, more fruit bowls.”

“And who else has a key to this door?” I asked.

“Arthur. Dr. Seward. Probably Quincy. The maid. The night man.” She turned from the glass. “Are you going to suggest I did it to myself?”

“I was gonna suggest if you wanted attention, you could’ve just joined a chorus line. But the way you look, you don’t need knife tricks.” I lit another cigarette and used the time it took to exhale to look around.

Neat room. Too neat. Even the fear had been vacuumed out and folded into drawers. But sometimes neat’s just what people do when their world gets messy. They put all the little things in order and hope the big ones follow.

“All right,” I said. “Here’s how this plays. I’m your new bodyguard. You had a scare, you panicked, you hired me. Simple. You tell your boys whatever version of that truth keeps them from throwing fits. Tonight, I stay in that armchair.” I pointed. “Tomorrow, I ask questions.”

“And if it… happens again?” she asked.

“Then maybe I see the teeth,” I said.

I met the men orbiting Lucy at dinner, in the hotel’s gilt-edged dining room where the steaks were rare and the customers were rarer.

Arthur Holmwood looked like the kind of man you see in magazine ads for better sweaters. Clean jaw, easy smile, expensive nervousness. He shook my hand like I was a laborer he’d borrowed from the street.

“Private investigator, eh?” he said. “Sensible, I suppose. Lucy always did have a flair for the dramatic.”

Quincy Morris was all Texas and sunburned grin, boots polished enough to see your sins in. He clapped me on the shoulder like we’d both just busted out of the same jail.

“Hell, Crow, I’m just glad she’s got another set of eyes on her,” he drawled. “Been a mite jumpy these last nights. I’ve been sleeping with a Colt under my pillow.”

“Just in case the rat’s got a gang,” I said.

His grin flickered, died. “I ain’t laughing much about it.”

Dr. Seward looked like a contradiction wrapped in a lab coat. Young and tired, meticulous and badly shaved. His eyes had that over-bright shine the addicted and the devout have in common.

“While I question the utility of… this line of defense,” he said, eyeing me like another symptom, “if Miss Westenra feels safer with you here, I am hardly in a position to argue. The mind needs its illusions.”

“You talk like that to all your patients, Doc?” I asked.

“They don’t all require so much… management,” he said. Then he noticed Lucy watching and smoothed his tone like he was folding linens. “We’re doing everything we can, Lucy. Professor Van Helsing arrives tonight. He’s… unconventional. But brilliant.”

“Unconventional how?” I asked.

“You’ll see,” Seward said.

He wasn’t wrong.

I caught the professor at midnight in Seward’s “clinic”—a suite refit with quiet carpets, soft colors, and little touches that tried to distract you from the reality that the only real difference between this and an asylum was the brand of liquor available.

Van Helsing was tall and slope-shouldered, in a suit that had been mended more times than a broken promise. His beard was trimmed neatly, but he’d missed a spot under his chin, the way men do when they’re thinking about anything but their own faces.

He looked me over with eyes like rusty nails.

“Ah,” he said. “The detective. You are late. Or perhaps you are just in the wrong story.”

“Name’s Crow,” I said. “And stories are how people explain things they don’t understand. Like death and taxes.”

He smiled faintly. “Yes. Or monsters.” He switched to a Dutch-accented English that felt like it came with footnotes. “Dr. Seward has told me much. And Miss Westenra—such a charming child, eh? So brave, even with all this… draining.”

“Draining?” I said. “You make it sound like a plumbing issue.”

“In a way, yes.” He lifted a case, clicked it open. Inside was a tidy array of oddments: little vials, odd-smelling herbs, a silver crucifix, a hammer, and what looked a hell of a lot like sharpened wooden stakes. I raised an eyebrow. He glanced at me. “I maintain an open mind, Mr. Crow. It is the only way to see what others do not.”

“I maintain an open tab,” I said. “Same idea.”

We stood there a minute, quiet except for the muffled mutter of some poor soul down the hall who was busy negotiating with ghosts.

“Lucy thinks someone’s trying to kill her,” I said. “Somebody keeps breezing past her locks, putting neat little holes in her neck. You got a theory?”

“Several.” He picked up the crucifix. “Some of them, you will not like. But the evidence…” He spread his hands. “It whispers in a certain direction.”

“Whisper it to me,” I said. “I’m good at listening.”

Van Helsing hesitated, then leaned in. His breath smelled like black coffee and old books.

“In my country,” he said quietly, “there are legends. Of a certain kind of criminal. The oldest kind.” He tapped two fingers against his own throat. “They take blood. They leave marks like little kisses of the grave. They control the weak, the sick, the… susceptible. They move by night. They do not die easy.”

“You’re talking about a vampire,” I said.

He watched my face. “You are familiar with the term.”

“I read the tabloids,” I said. “And fairy stories, when sleep won’t come. Professor, with respect—this is a hotel in a nasty city, not a castle in the Carpathians. If there’s a bloodsucker around here, he’s got a business card and a good lawyer.”

“Perhaps,” he said. “But still. Humor a foolish old man, yes? You watch. You see. You keep your revolver if you like—” he glanced at my coat, where the weight on my left side hung like a promise—“but you keep your eyes open for more than men with guns. There are older weapons.”

“You really believe that?” I asked.

“I believe in harm,” he said. “It has many uniforms. I do not discard one simply because it is not in fashion.”

I left him to his herbs and hardware and went back upstairs. The night smelled wrong. Too still. Like the city was holding its breath and waiting for the punchline.

Around two in the morning, the building quieted the way a drunk does when he finally runs out of lies. Lucy lay in that big bed like something delicate they’d forgotten to put behind glass. I took the armchair in the corner, where I could see the door, the bed, and most of my mistakes.

“You believe him?” she asked in the dark. Her voice floated up light, like she was afraid the room might not permit it.

“About the vampires?” I said. “Lady, I don’t even believe in honest men.”

“But something is… happening to me,” she said. “You felt the air, didn’t you? The way it changes. The way the nights feel… slower.”

I shifted. My leg had gone to sleep. The rest of me was working overtime.

“There’s always a reason,” I said. “Might be an old story with a long shadow. Might just be a man with a strange set of tools. Either way, it leaves fingerprints.”

“Are you always this calm?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “Sometimes I get jumpy and start asking for a raise.”

It pulled a small laugh from her. Then silence. The curtains breathed slowly with the draft, in and out, like a big sleeping beast.

I must’ve dozed. Whisky’ll do that, and so will nights that have too much in them. One minute I was tracking the slow, easy rise and fall of her breathing, the next I was… somewhere else. Not quite asleep, not quite awake. Like the room had been drowned in thick, dark honey.

Something pressed against my chest. Not hard. Just enough to tell me who was boss. I tried to move my hand; it might as well have been nailed to the armrest. The air had gone cold, but not the kind of cold you get from a draft. The other kind. The grave kind.

And then I heard it.

Not footsteps. Not the creak of a window being jimmied. Just… a sigh. Right next to my ear. Long and thin and hungry.

My head felt stuffed with cotton. I fought it, dragged my eyes open. The room swam, blurred, settled in strange colors. I saw the bed. I saw Lucy. I saw—

Something else.

It was bent over her, long and dark, stretched thin as a shadow. Not quite man, not quite mist. Just… absence, poured into a man-shaped bottle. Its head was buried at her throat.

My fingers twitched toward the gun under my arm. The move cost more effort than it should have, like I was pushing through thick water.

“Get away from her,” I tried to say. It came out like a drunk whispering a secret.

The thing lifted its head.

I’ve seen dead men in alleys with more warmth in their faces. It didn’t even turn all the way toward me; just a sliver of a profile, chalk-white, lips red in the dark. Its eyes… well, I didn’t see them. Not clearly. Just felt them, like two nails driven into my skull.

My thumb scraped the hammer of the Colt. Somehow, that little metallic click carried. The thing cocked its head. If a shadow can smile, this one did.

Then it was gone.

No motion. No rush. Just… blink, and the space where it had been was empty, and the curtains on the window stirred like something fat and satisfied was dragging itself out through the glass.

I could move again. All at once. The spell—if that’s what it had been—snapped like cheap string. I stumbled to the window, swore at the pain in my half-dead leg, yanked the curtain back. The glass was latched. Tight. No cracks. Just my face in the reflection—pale and pissed.

Behind me, Lucy moaned.

I went to the bed. Her silk at the throat was pushed aside. Two neat wounds, like twin punctuation marks, sat there, weeping a little blood. Her skin had the color of old newspaper.

Her eyes fluttered open.

“Did you see him?” she whispered.

“I saw something,” I said, my voice tight. “Next time, I plan to introduce him to the Second Amendment.”

“Next time,” she breathed, “he won’t let you move at all.”

I believed her.

Morning came in yellow and gray. Arthur, Quincy, Seward, and Van Helsing crowded the room like four suits fighting over the same coffin.

“You’re sure the window was secure?” Seward asked, voice clipped. He’d had a bad night. The kind that leaves lines on the face and chalk dust in the soul.

“Positive,” I said. “Lock’s in better shape than my liver.”

“And you… saw this intruder?” Van Helsing prodded.

“I saw something,” I said. “Enough to know he’s real. Enough to know your stories aren’t just for campfires.”

Arthur scoffed. Crossing his arms, he looked at me like the help had spoken out of turn.

“A vampire?” he said. “Really, Professor. This is the twentieth century.”

“Evil does not check its watch, Lord Holmwood,” Van Helsing said coldly. “It simply adapts its wardrobe.”

Quincy was quiet, chewing an invisible piece of tobacco. His hand flexed on his belt, where no gun was allowed within hotel rules.

“So what do we do?” he asked finally.

Van Helsing took a breath. “We make certain precautions.”

Which is how I found myself, hours later, helping an old Dutchman turn a five-star hotel room into a bedroom for a very frightened saint.

He had us hang garlic—real, raw, stinking garlic—over the windows and door. He pressed a small silver crucifix into Lucy’s hand and murmured something that might’ve been Latin or just the sound a man makes when he’s trying not to cry.

“Is all this necessary?” Arthur demanded, watching his pedigree wilt under the assault of working-class herbs.

“I don’t know,” Van Helsing said. “But I have seen enough not to underestimate old tools. And if this fails, we try another way.”

“What other way?” I asked.

He glanced at the case by the door. The hammer. The stakes.

I didn’t like the way he looked at Lucy when he said it.

Two nights later, the thing came back.

It didn’t bother with parlor tricks this time, or maybe I was just more braced for them. The air thickened again, but I fought it, clinging to consciousness like a man clings to the last cigarette in the pack.

I heard the window rattle. The garlic swayed like little white skulls on their strings. The crucifix around Lucy’s throat—Van Helsing had insisted—glinted in the dark.

Shadow slipped through the room, thinner than smoke, heavier than fear. It came for the bed like it had a long-standing reservation.

I’d moved my chair. This time I was between Lucy and the window.

“Evening,” I said, and fired.

The Colt roared in the dark. The muzzle flash carved the room into a stuttering cartoon. For one frozen frame, I saw its face—long, tired, hungry, like an old aristocrat who’d outlived his money and his morals. The bullet hit, I think. It jerked—not like a man, more like a coat snagged on a nail.

But it didn’t fall.

It hissed. Not in my ears, not quite. In my head. Something hot lanced through my skull, down my arm. My fingers spasmed; the gun flew from my hand, clattered under the dresser like it had suddenly decided it wanted no part of this story.

Then it moved.

Fast, so fast my eyes couldn’t keep up. One moment near the window, the next a breath from my face. I smelled something old and dry, like museum dust and spilled prayers.

“You’re not the first man to stand between me and what I want,” it whispered.

The voice wasn’t in the air. It was in me. In the bones.

“Yeah?” I said, through teeth that didn’t quite remember how to work. “How many of them were packing silver?”

It laughed. Low and contemptuous. “You’re not, detective.”

And then, behind it, Lucy spoke.

“Get away from him,” she said.

There was something in her voice I hadn’t heard before. Not fear. Not the brittle bravado she wore like perfume. Something sharp. Something old.

The thing turned.

She sat up in bed, pale and sure, crucifix burning against her throat. Her eyes were wide, not empty anymore. Full of recognition. Of horror. Of something that hurt worse.

“I know you,” she whispered.

For a second, the thing froze. If it had a heartbeat, it skipped.

“Lucy,” it said. Like the name tasted better than blood.

My hand, forgotten on the chair arm, closed around something cool and hard. I didn’t remember dropping it there, but my fingers knew the shape: the little vial Van Helsing had pressed into my palm “just in case.” Holy water, he’d said. I didn’t believe in the word in front, but I believed in the look in his eyes.

I threw it.

The glass broke on the thing’s shoulder. There was a sound like somebody stepping on a live wire. Light—cold and sharp—crawled over its coat, its skin, wherever it touched. It sizzled, smoked. The smell made my stomach roll.

The thing screamed. This time the sound made it out into the open air, a high, ragged shriek that set teeth on edge and killed a lightbulb in the hall.

Then it was gone. Out the window, ignoring the lock like locks were for men. The glass didn’t break. It just… stopped mattering for a second.

Lucy slumped back, eyes rolling. Her breath came thin and fast.

I grabbed the crucifix, pushed it back into her hand.

“Don’t let go,” I said. “Not even if he whispers sweet nothings in your ear.”

“His name,” she gasped. “He… he had a name.”

“Yeah?” I said. “Did it come with a return address?”

She stared at the ceiling. “He said… once… he was a count.”

I swore, soft and savage. The newspaper clippings, the rumors Van Helsing had half-muttered about some European industrialist with a trail of drained corpses behind him—they all stacked up in my head like bad cards.

“Doc was right,” I said. “And I hate it when the doctors are right.”

The next day, over black coffee in Van Helsing’s cluttered little office, we made plans.

“He has tasted her,” Van Helsing said. “He will not want to let her go. She is… how you say… hooked.”

“You make it sound like dope,” I growled.

“In a way, it is,” he said. “He needs her blood; she… feels what he offers. No one else sees it, but for her, perhaps, it is like a… a lover. One who takes more than he ever gives, but still, there is a tie.”

“I saw her eyes,” I said. “That wasn’t love.”

“No,” he agreed quietly. “That was recognition.”

“Who is he?” I asked.

Van Helsing sighed. “He has had many names. In this city, perhaps he has another. But in the old world, where I come from, they whisper about one in particular. A nobleman. A warlord. A man who made cruelty into art.” He looked up. “They called him Count Dracula.”

Names again. Names with weight. Names that left marks.

“So what’s the play?” I asked. “We going to put garlic on every window in town? Hire a platoon of priests?”

“We set a trap,” he said simply. “We give him what he wants. He comes. We end it.”

“You’re talking about Lucy,” I said.

His silence was a kind of agreement.

“Hell no,” I snapped. “She’s the mark, not the bait.”

“She is both, Crow.” Van Helsing stared at me, tired and unyielding. “She is already marked. If we do nothing, he takes her. If we run, he follows. He is old, and patient, and cruel. Men like you and me—we are just… what is word… scenery. She is the story.”

“I thought I was in the wrong story,” I said.

He didn’t smile. “You are now. But you are here. So you choose: do you help me end this, or do you step aside and let the monster finish his meal?”

I lit a cigarette to have something to do with my hands. The match flame shook. I told myself it was the draft.

“Lucy gets a say,” I said.

“She is ill,” he said. “Weaker every night. He takes, and takes—”

“She’s still got a voice,” I cut in. “I heard it last night, and it wasn’t a whisper. We ask her.”

She said yes.

Not like a martyr in a painted window. Not bravely, not calmly. She shook, and she cried a little, and she hated all of us—especially herself. But she said yes.

“If he wants me,” she said, each word like a pulled tooth, “then let him come. Let him come when you’re ready for him. Better me than… than anyone else.”

“You’re a fool,” I told her.

“I know,” she said. “But I’m a Westenra. We’re trained for it.”

Arthur tried to argue, but his kind of love is soft and selfish; it doesn’t know what to do with sharp edges. Quincy just nodded once, jaw clenched. Seward wrote something in his little book, hands shaking.

We prepared the room. Not like before. This time the garlic went inside the window frame, hidden by the curtains. The crucifix stayed on her skin. Van Helsing placed little phials of water around the room like landmines. Under the bed, by the dresser, in the chair where I sat. He pressed something cold and smooth into my hand.

“A stake,” he said quietly.

“Feels like bad carpentry,” I muttered.

“Use the pointy end,” he said.

“Professor, I’m still not sold on the bedtime story,” I said. “But I saw enough to know this much: whatever he is, he’s not walking out of here again if I can help it.”

“He is already dead, Mr. Crow,” Van Helsing said. “Walking is a habit he has not yet broken.”

Night came down hard.

Lucy lay in the bed, crucifix glinting faintly in the low light. Her skin was almost translucent now, thin and fragile as cigarette paper. But her eyes were clear. Fear hid in them, but so did something else. Something like resolve.

Arthur, Quincy, and Seward waited in the adjoining room, door cracked. Van Helsing sat by the wall like a tired old vulture. I took my chair, stake in one hand, gun in the other. Maybe one of them would matter.

We didn’t talk. What was there to say? The garlic smelled like an old kitchen. The city outside kept doing business, oblivious.

Around two, the air changed.

Not a sound, not a movement. Just… pressure. Like a hand on the back of your neck. The hairs on my arms sat up and requested hazard pay.

Lucy’s breathing hitched. Her lips parted. “He’s coming,” she whispered.

“Tell him we’re full up,” I said. My voice didn’t sound like mine.

The curtains stirred. No wind. Just… motion. Like someone was walking through them from the wrong side. A darker dark bled into the room, pulling itself together into the line of a man.

Count Dracula stepped into the light.

He wore the sort of suit that’d been stylish fifty years ago and never really gone out of fashion in the circles he traveled in. Black, precise, immaculate. His face was pale and fine-boned, not handsome exactly, but compelling, the way a gun is. His eyes were dark, bottomless. His mouth was a thin red line.

“Lucy,” he said. Not to us. Just to her. “My dear.”

She made a small broken sound. “No.”

He smiled, slow. “You invited me once, when you were so lonely you thought your heart might stop just to end the boredom. Did you think I would forget?”

“You’re not welcome,” I said, standing.

He looked at me like a man looks at a fly that’s landed on his dinner.

“And you are?” he asked.

“Nate Crow,” I said. “House detective. And I’m closing the bar.”

He laughed then, a dry, hollow thing. “Men. Always so sure a little noise and a little metal make you important. Stand aside.”

I didn’t.

His eyes met mine. For a second, the whole world narrowed down to that dark gaze. It bored in, cold and deep and hungry. Something in my head wanted to kneel. To step back. To say: Sure, pal. She’s yours. Never liked her anyway.

I gritted my teeth and held on. Pain flared behind my eyes like somebody’d set off a Roman candle in my skull.

“You are… stubborn,” he said thoughtfully. “I have eaten kings for less insolence.”

“Yeah?” I said hoarsely. “Maybe that’s your problem. Too many rich meals. Bad for the heart.”

He moved.

Fast, so fast the air snapped. One second he was across the room; the next his hand was around my throat. Long fingers, cold as ice and strong as a rumor that ruins men.

He lifted me. My feet left the ground. The stake slipped from my fingers, clattering uselessly. My gun was pinned between us, barrel pointed somewhere at the ceiling. I scrabbled at his wrist, felt bones under the skin—old, hard, unyielding.

“You try to take what is mine,” he said softly. “Little detective. Little man, with your little questions. Go to sleep. I am gentle with children.”

The edges of my vision sparked. Black and white fireworks. Somewhere behind him, I heard Van Helsing shout something, words in a language that had dust on it. There was a flare of yellow light. Dracula hissed, flinched, but didn’t let go.

Lucy screamed.

It cut through everything. The pressure. The pain. The darkness. She screamed his name—not the title, the old one, the one that had been his before he ever drank blood. I didn’t catch it. Didn’t need to. The way she said it, it wasn’t a name anymore. It was a sentence.

Dracula’s head snapped toward her. Just for a second.

It was enough.

My thumb banged down on the Colt’s hammer. The gun bucked between us. At that range, even a drunk couldn’t miss. The bullet hit him dead-center in the gut, point-blank.

He jerked. Not from the wound. From surprise.

“You…” he began.

Then Van Helsing’s hand shot out, shoving the fallen stake into mine. I didn’t think. I just moved.

The point found his chest just below the breastbone. It met resistance—hard, ancient, stubborn, like everything else about him. Then it slid through.

His eyes went wide.

For a heartbeat—for his first honest heartbeat in centuries, maybe—he looked human. Just a man with a hole in him, astonished at the idea that the world could say no.

Then time caught up.

Black blood spilled over my hand, thick and cold. He made a sound that wasn’t anything living makes. His grip on my throat loosened. I sucked in air like a drowning man. Van Helsing was shouting something, Quincy and Arthur burst in, the door smashed open, Seward gasped.

The room filled with chaos.

Dracula staggered back, clawing at the stake. His skin was graying, cracking, like old plaster in a burning house. Light—thin and mean—leaked out of the cracks.

“No,” he rasped. “No. Not… for her. Not for… you.”

“You should’ve stayed in your castle,” I said, because sometimes words are all you have left.

He looked at Lucy one last time. There was something like regret in it. Or hunger. Or maybe that’s the same thing when you’ve lived as long as he had.

Then he fell.

Not like a man. Men hit the ground and stay there. He… crumbled. Turned to dust and ash and something empty, blowing away on a wind that had no business in a sealed hotel room.

In the silence that followed, my own breathing was the loudest sound. Then Lucy sobbed once, sharp and raw.

“It’s over,” Van Helsing said hoarsely. “For now.”

“For now?” I croaked, massaging my bruised throat.

“There are always others,” he said. “There is always hunger. But this one… this one is done.”

Lucy looked… better. Not well. But some color had tiptoed back into her cheeks. The wounds at her throat weren’t gone, but they seemed smaller, less greedy.

“I… feel… strange,” she murmured.

“Welcome to the club,” I said.

It took money and pressure and a few well-placed lies to keep the whole mess out of the papers.

Official story: an intruder, a madman from Seward’s clinic, gone off his rails, attacked Miss Westenra in her sleep. Struggle, gunshots, intruder dead and unidentifiable, burned in a small accidental fire that started when some fool knocked over a lamp. Tragic. Shocking. Very discreet.

Arthur signed a lot of checks. Quincy shook a lot of hands. Seward drank more than he should and wrote less than he needed to.

Van Helsing disappeared two days later, leaving only a note on my desk that said:

Do not forget what you saw. The world is not so small as you think.

—A.V.H.

Lucy left the city a week after that. “Rest cure,” they called it. Some place on the coast where the sea is supposed to wash sins and bad memories away. We said goodbye in the hotel lobby, under the chandeliers and the ticking whispers of rich people who’d never know what it meant that the air felt a little lighter.

“Will he ever be… really gone?” she asked.

“Men like that,” I said, “even when they’re dead, they leave a long shadow. But you’re not in it anymore.”

She studied me. “You saved my life, Mr. Crow.”

“I was just the guy holding the stick,” I said. “You did the hard part. You let him go.”

“Did I?” she murmured.

I didn’t have an answer for that.

She offered me her hand. I took it. It was warm. Human. That felt like a victory.

“If you ever need anything,” she said, “you know where to find my lawyers.”

“Oh, sure,” I said. “And if you ever need anything, you know where to find me. Third floor, leaky ceiling, bad coffee.”

She smiled then, a real one. It made her look younger. Less haunted.

“I hope I never see you again, Mr. Crow,” she said.

“Likewise, Miss Westenra,” I said.

She left in a black car with a driver who looked like he’d take a bullet for a good tip. The door closed, the engine purred, and she was gone, folded back into the world where girls like her belong.

I stood on the sidewalk, watching the rain smear the city.

The night didn’t feel quite as heavy anymore. But it was still there, waiting in the alleys, in the hotel rooms, in the hearts of men who didn’t need fangs to drink a person dry.

My office waited for me, up those dusty stairs. Inside there were bills that needed paying, and a bottle that needed emptying, and a typewriter that occasionally behaved itself.

I lit a cigarette and started walking.

Monsters are real. I’d seen one up close, smelled his breath, put a stake through what passed for his heart. But the funny thing was, he wasn’t so different from the rest of the city. He just didn’t bother pretending.

The rest of them do. The bankers, the politicians, the smiling boys with clean nails and dirty souls. They all take their bite. They all leave people pale and weak and wondering what the hell just happened to them.

Me? I work nights. I keep an eye on the shadows. I make sure at least one girl like Lucy Westenra gets to walk away, even if she’s a little less innocent than she was when she stepped into my office.

In my line of work, that counts as a happy ending.

NotebookLM

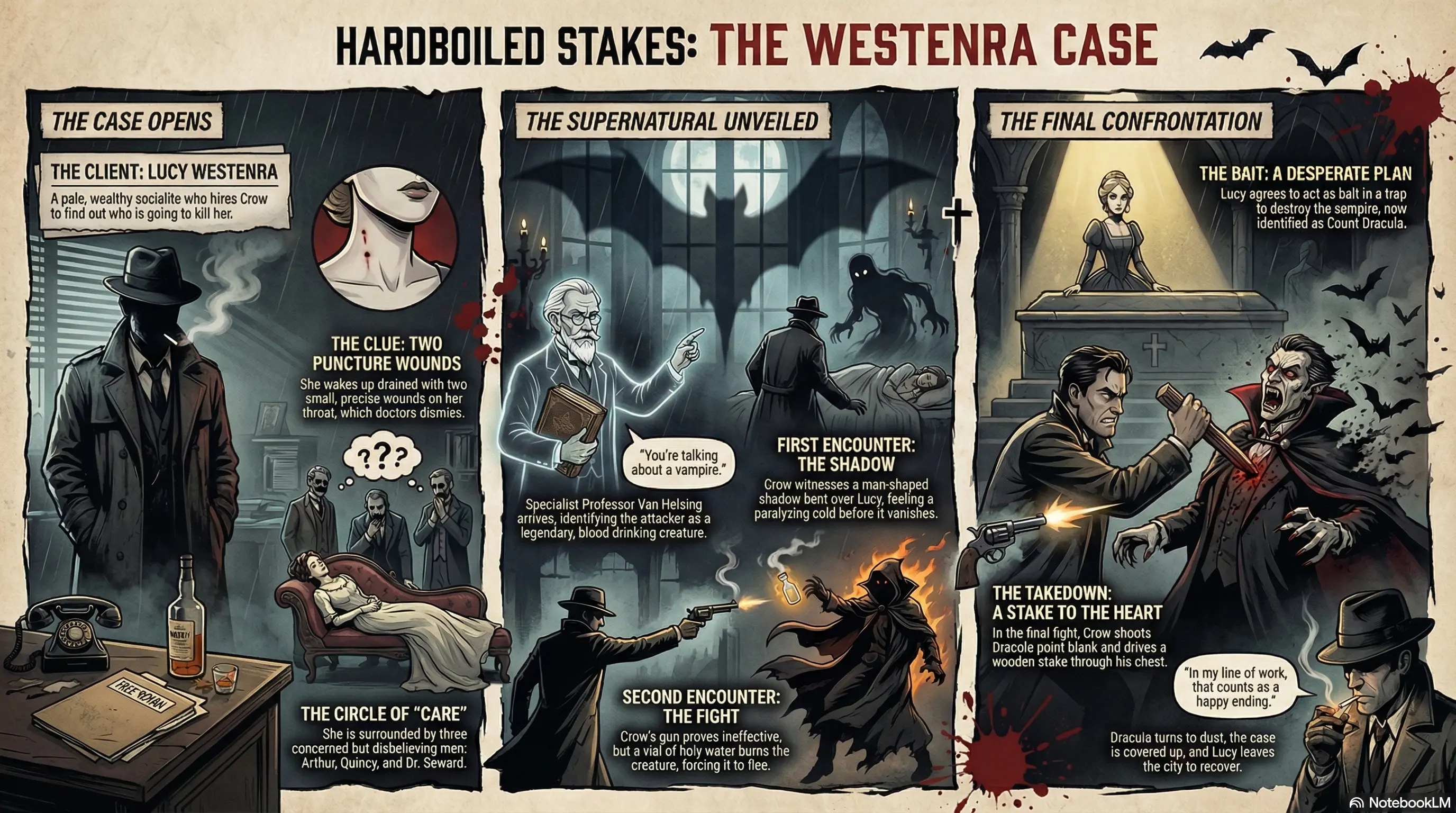

NotebookLM once again surprised me with its output. It generated a stylish infographic …

… a set of atmospheric slides …

… and an interesting analysis …

The analysis by NotebookLM highlights some interesting points:

- The story boldly merges two clashing genres — noir grit and Gothic horror — right from the opening, making it “something else entirely.”

- It builds a tension between Crow’s hard realism and Van Helsing’s ancient metaphysics, a collision that becomes undeniable when “the rules of his world just don’t apply anymore.”

- NotebookLM identifies the core theme in the line “ancient evil… puts on a modern suit,” treating it as the story’s central meaning rather than just atmosphere.

- The ending lands on a deliberately unresolved moral question — “What do you do about the evil that wears a smile…?” — a closing move typical of literary fiction, not mere pulp.