Are we there yet? Can AI produce art?

November 30, 2025

This weekend I had a little time to play around — and ever since ChatGPT arrived back in 2022, I’ve been wondering when AI would be ready not just to help with creativity, but to actually create something that feels like art. Or at least: good, fun pulp fiction.

So I ran a little experiment.

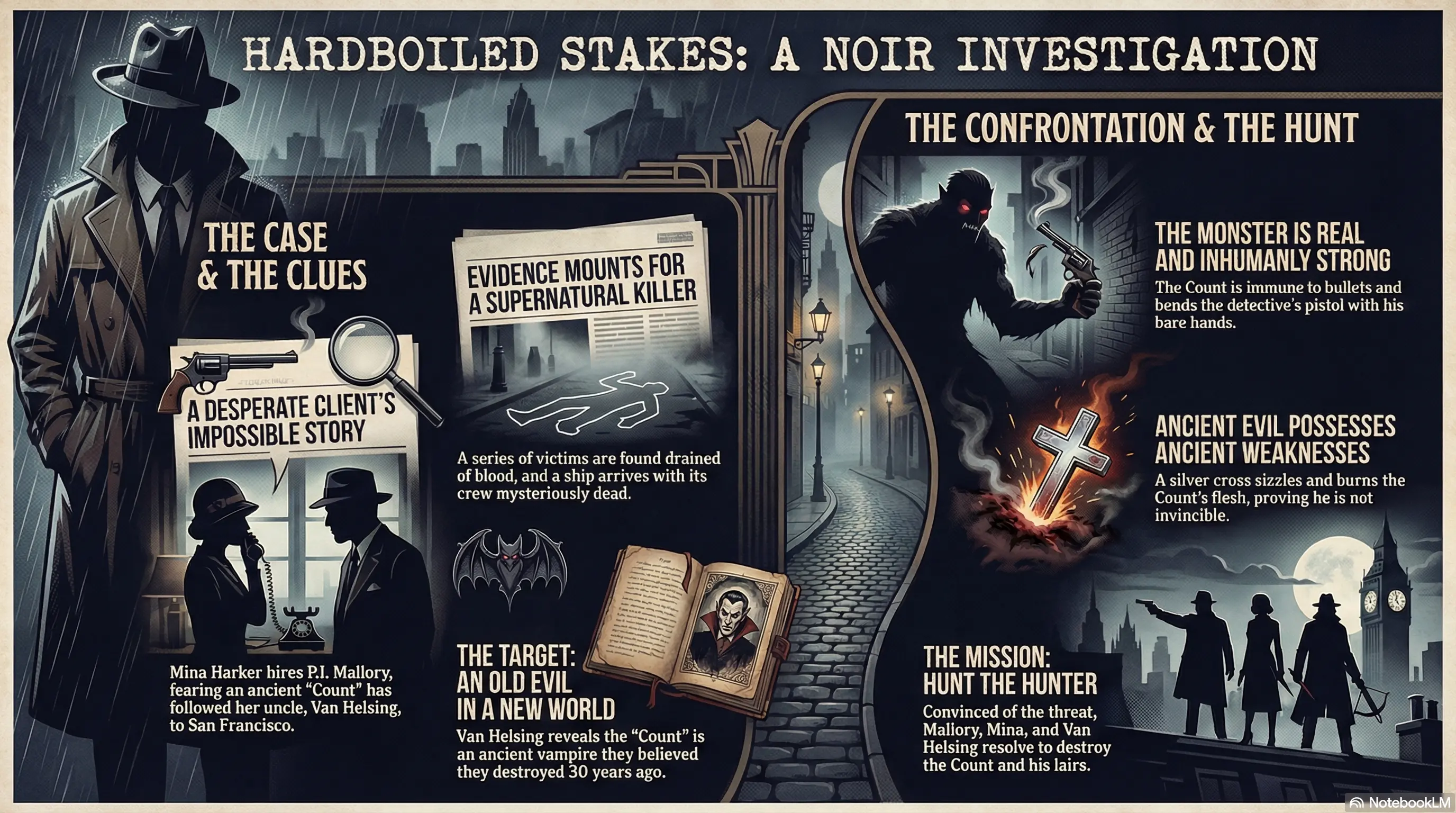

Using ChatGPT 5.1 with high-reasoning mode, I asked it to generate a short story that mixes classic Dracula with a 1920s hardboiled detective atmosphere á la Dashiell Hammett. Afterwards, I fed the material into NotebookLM to produce some media around it — an infographic, slides, and even a bit of analysis.

And honestly? I’m surprised. Some of the dialogues were sharp, the atmosphere was consistent, and several pieces of generated artwork were far better than I expected. Definitely the kind of pulp fun the AI and I can cook up together — perfect for a rainy afternoon read.

Hardboiled Stakes in the Fog

“Van Helsing?”

The name dropped onto my desk like a dead moth. Small, ugly, and older than it had any right to be.

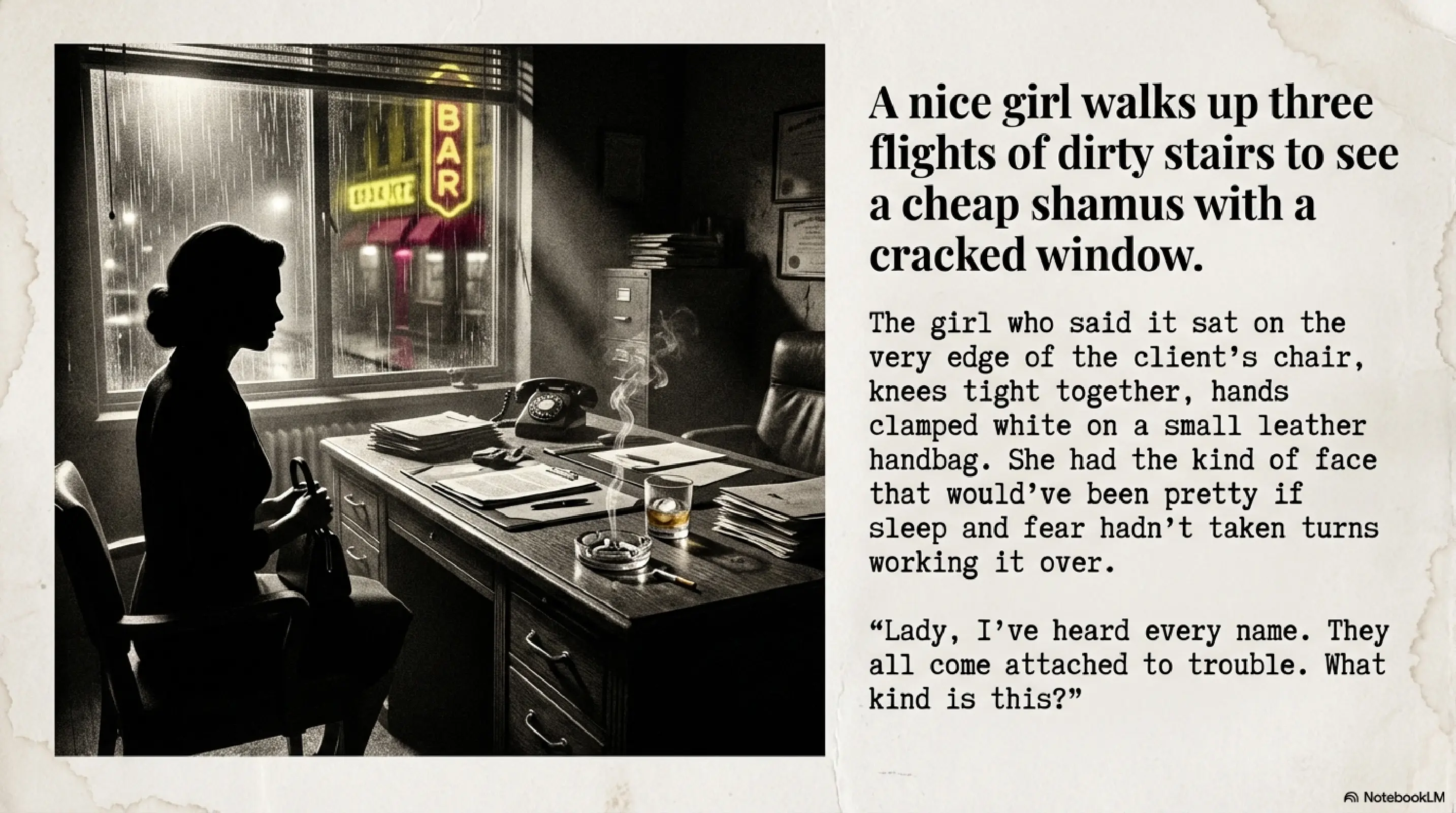

The girl who said it sat on the very edge of the client’s chair, knees tight together, hands clamped white on a small leather handbag. She had the kind of face that would’ve been pretty if sleep and fear hadn’t taken turns working it over the last few nights. Lips chewed raw. Eyes too big. Blouse too thin for the November rain crawling down the window like it was looking for a way in.

“Yeah,” I said. “I heard you. Van Helsing. Spell it if you like, I’ll still think it sounds like a Dutch brand of cheap tobacco.”

She didn’t smile. Some people don’t know a joke when they hear it. Others don’t have the room left inside to laugh. She was the second type.

“He’s real,” she said. “You’ve heard the name, haven’t you?”

“Lady, I’ve heard every name. They all come attached to trouble. What kind is this?”

She swallowed. Her throat worked like she was trying to get the word past something tight and painful.

“Vampires,” she said.

I lit a cigarette and watched the smoke crawl up, slow and patient. Outside, the city coughed and wheezed and went on being lousy.

“Sure,” I said. “And the bogeyman’s working the night shift down on Market Street. Try me again. Straight this time.”

She sat up a little, pushed a loose lock of hair behind her ear. There was a stubborn line in her jaw. I’d seen it before on men headed for the gallows and dames about to say “no” when “no” meant a beating. That kind of line doesn’t bluff.

“I mean it, Mr. Mallory,” she said. “Abraham Van Helsing. The doctor. My uncle.”

That got my attention a little. Not the vampires. The way she said his name. Not like she’d read it in a dime dreadful. Like she’d sat across from the old buzzard at the breakfast table and passed the marmalade.

I tipped ash into the tray. “All right, Miss…?”

“Harker. Mina Harker.”

I looked at her again. The name scratched at something soft in the back of my skull. An old newspaper clipping. A long story told too quiet in some bar on a wet night. Europe. A lunatic with a title and a habit. A professor and a circle of friends who’d hunted him down.

I let the cigarette hang of its own weight.

“Harker,” I said. “Any relation to—”

“Yes.” She cut me off fast. “They were my parents. Jonathan and Mina. They’re dead.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You don’t need to be. They died a long time ago.”

She looked it, too. Not in the face. In the eyes. The eyes were older than the rest of her, like they’d seen their share, and then their neighbors’ too.

“Go back to the beginning,” I said. “And keep it tight. Start with why a nice girl walks up three flights of dirty stairs to see a cheap shamus with a cracked window and a liquor bill he’s on the losing side of.”

Her fingers worked the clasp of the handbag. Metal clicked soft and nervous.

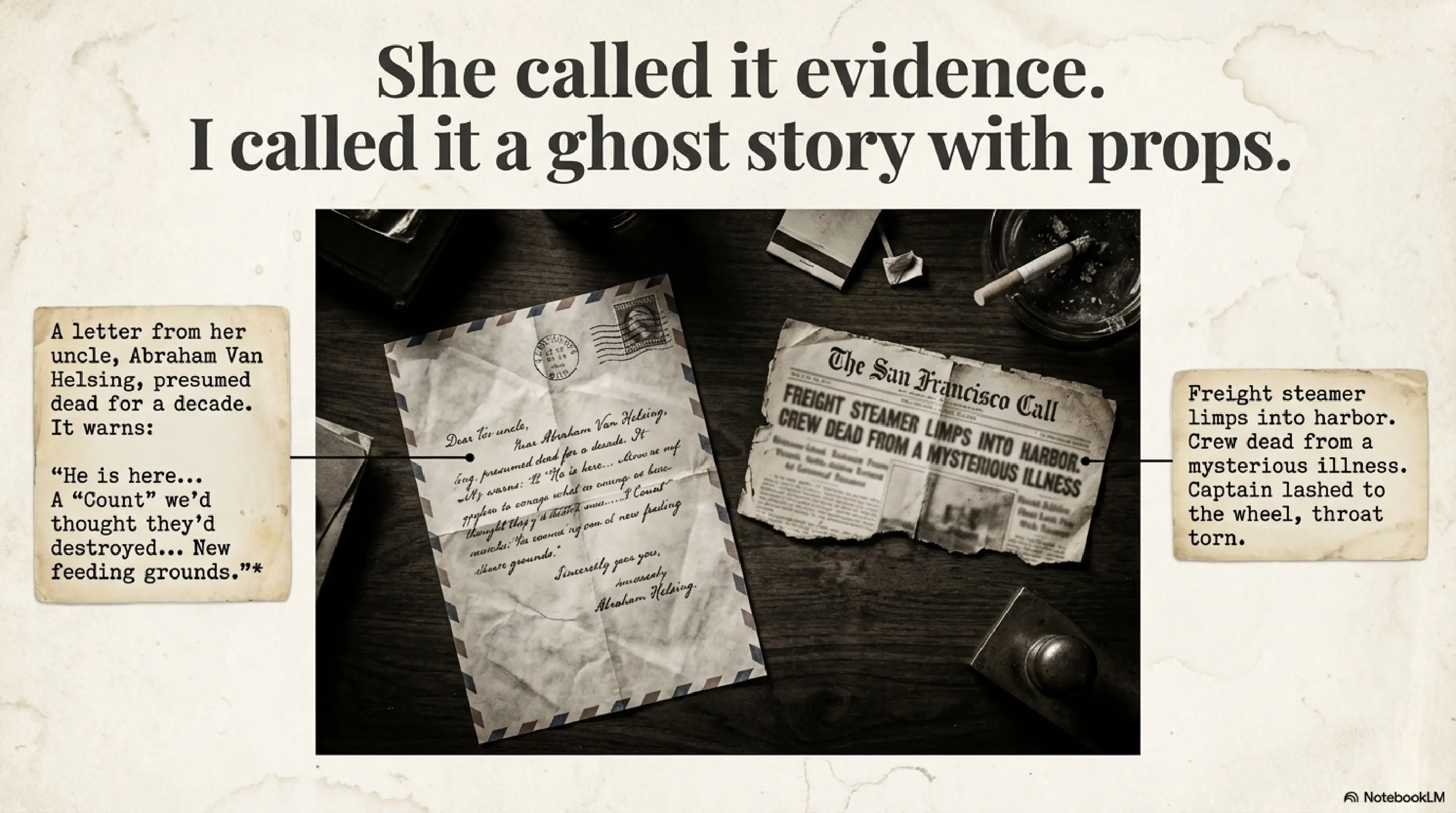

“I had a letter,” she said. “Two weeks ago. From Amsterdam.”

“Bad news or worse news?”

“Both.” She fished it out and laid it on my desk. Thin paper, foreign stamp, neat old-man handwriting that looked like it needed spectacles and a warm fire. “He’s alive.”

“Who?”

“My uncle. Van Helsing. We thought he was dead. For years. There was… an arrangement. When he passed, a solicitor was supposed to let us know. That was more than a decade ago.”

“So your dead uncle writes you a letter from Holland. Could be worse. Could be a bill.”

She didn’t flinch. “Read it.”

I picked it up. The paper smelled faintly of dust and something sharp underneath, like old medicine.

Miss Harker—

Forgive the long silence of an old man who has seen too much of the night. I have delayed, and it is a sin. But it is a greater sin to let terror come and give no warning.

He is here.

The words went on. Careful, stiff English with a Dutch accent hiding between the letters. Hints about a “Count” he’d thought they’d destroyed. Evil that never truly died so long as someone somewhere still invited it in. A ship. A voyage to America. New feeding grounds.

I flicked my eyes up. “This the part where you tell me about garlic and stakes and crosses and the power of love?”

Her mouth tightened. “You don’t have to believe any of it, Mr. Mallory. I barely do myself. But three nights ago, a dockworker was found in an alley down by the Embarcadero. He’d bled out. Completely. No knife wound. Two punctures on his throat.”

“Cops say what?”

“‘Rats,’” she said, with a flat little smile that belonged on a much older woman. “Very tidy rats that only take blood and close the skin neatly after. Yesterday it happened again. Another man. Same way.”

I’d heard about that, sure. Coppers gossip like old maids if you know where to listen. They didn’t like it because it didn’t fit in the usual shapes. No robbery. No grudge. No dame screaming murder. Just white faces and drained veins.

“Coincidence,” I said. “Could be some nut with an ice pick and imagination.”

Her eyes flashed. “And the boat?”

“Boat?”

She reached back into the bag, came out with a clipping from the Call. Freight steamer from Europe limping into harbor five days late. Crew dead from a mysterious illness. Captain lashed to the wheel when they boarded, eyes wide, throat torn.

“I know what it sounds like,” she said. “I know I sound like a hysteric. I’m not. I grew up with secrets, Mr. Mallory. My parents told me stories, and then they told me to forget them. I never saw my uncle. I only knew that somewhere there was an old man in a city of canals who kept watch over a grave that wasn’t a grave. And now he writes me that the grave is empty, and blood is spilling, and he is coming here, to San Francisco, on ‘the trail of darkness.’ Those are his words, not mine.” She sucked in a breath. “He asked me to meet his ship tomorrow night. At the docks. Pier Seven. Midnight.”

“And you want company,” I said.

“I want a man who knows how to look at evil and not blink. I was told you used to be a cop.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I used to be lots of things. Most of ’em don’t pay so good now.”

“I can pay you.” She pushed the bag toward me. It thunked with the polite, promising sound of folded bills. “Fifty now, a hundred when it’s done. Just come with me. Listen to what he has to say. Help me, if… if there’s something real here.”

Fifty clams wasn’t nothing. It would keep the landlord from practicing his right cross on my door for another month. It would put real food in the icebox instead of liquid bread from the corner bar. And anyway, I was curious. Curiosity had gotten better men than me killed. It had also won them a few cases.

I tapped ash, watched the way her fingers shook just a little.

“All right,” I said. “You’ve bought yourself a bodyguard with a skeptical nature. We’ll go see your Dutch uncle. But if this turns out to be a family reunion and a ghost story, you’re picking up cab fare.”

She smiled then, small and fragile. But it was there.

“Thank you, Mr. Mallory.”

“Don’t thank me. Not until we know who’s paying for the flowers.”

Pier Seven at midnight is the kind of place the city tries to forget it has. By day it’s all crates and curses, men in caps moving the world in wooden boxes. By night, everything leaks oil and shadows. The fog comes in off the bay and piles itself against the pilings like it’s too tired to go on. Ships loom up out of the soup, tall and black and silent, like the bones of dead whales no one had the decency to bury.

We stepped down off the rattling cab and into the wet, cold dark. I flipped the driver a bill and he disappeared like he’d been glad to get us off his back seat.

“You sure about this?” I asked Mina.

“No,” she said. “But that’s never stopped anything before.”

There was one ship tied up near the far end. A small passenger steamer, shabby but clean, with a chipped white hull and a name spray-painted in flaking black on the bow: Helena. There was a single lantern up by the gangway, burning sickly yellow.

At the foot of the gangplank stood a man in an overcoat that had seen better decades and a hat that might once have belonged to a professor, or a clown, or a corpse. He was short and stooped, wrapped too tight in himself, like he was afraid the world might leak in through the seams. When he turned at the sound of our footsteps, the lantern caught his face.

I’ve seen old men. Cops retire, winos age, judges go gray and soft. This was something else. The bone structure was good, the eyes were clear and sharp and light, but time had whittled that face with a vicious little knife. There were lines on his lines. Each one seemed to carve a story into the next. His beard was neat and yellow-white. His mouth was kind, or wanted to be. It had forgotten how.

“Miss Mina,” he said. His accent was heavy and sweet, coating the words like syrup on bad pancakes. “My child. My dear child.”

She froze for half a second, then moved forward fast. “Uncle Abraham.”

They didn’t hug. They just stood close, like two people leaning toward a fire, not sure yet how hot it burned.

“This is Mr. Mallory,” she said. “The detective I told you about.”

He turned to me. Those pale eyes went over me the way a coroner looks at a slab. Not hungry. Not polite. Just professional. Taking stock of the meat.

“You were policeman, yes?” he said.

“Once upon a time.”

“Good. You have seen already the worst of which men are capable. So when I tell you there is more—worse, older—you do not say immediately, ‘Bah, the old man has too much schnapps, he tells fairy tales.’”

“I don’t say ‘bah,’” I said. “But the rest is on the table.”

He smiled. It made him look even older. “You do not believe in vampires, Mr. Mallory?”

“I believe in men who will take anything that isn’t nailed down, and a few things that are. If they’ve got no pulse, that’s the coroner’s problem.”

“Ah.” He nodded. “Good. Skepticism. It is like silver—purifies nonsense, yes? But I tell you this. When the skeptic sees, he breaks or he hardens. Pray that you harden.”

The way he said it, softly, almost tender, put a little ice cube down my spine.

“We can talk in my cabin,” he went on. “There are ears in the fog.”

We climbed the gangplank. The Helena smelled of salt and rust and linseed oil. The decks were mostly dark, just a few hatch lights glowing dull. No crew in sight. The ship felt too quiet, like a joke waiting for the punchline.

His cabin was small and cramped, books piled up on every flat surface, the kind of medical clutter that would give a health inspector a conniption fit. Bottles. Syringes. A scalpel or two that looked too used.

He sat on the edge of the narrow bunk, hands on his knees, fingers twisted together. “You have the letter?” he asked Mina.

She produced it. He didn’t read it—he only touched it, like a priest with a relic.

“I wrote in haste,” he said. “We were already chasing his shadow. In Amsterdam, there were two deaths. In Hamburg, three. On the ship, there were… others.” His eyes went far away. “He is clever. So clever. He knows now the modern tricks. He leaves behind no simple, easy superstition. Only corpses with wounds that explain themselves if you do not look too long. You understand?”

“No, but keep talking,” I said.

“We thought we killed him thirty years ago,” he said. “We cut off his head, we burned his heart, we filled his mouth with garlic and his grave with holy earth. We were so very young then, even those of us who were already old.” A ghost of bitter humor crossed his face. “Evil is persistent. A little piece survives here, a drop of blood there. A servant, a disciple, someone who thinks, ‘Ah, but what if I keep a bit, yes? What if I sell it, use it, worship it?’ Men, Mr. Mallory. Always it comes back to men. Monsters cannot live without them.”

“And now?”

“And now he comes here,” Van Helsing said. “Why not? This America, it is a young land. Hungry. It likes things that grow fast. He has always liked hunger. He rides it like a horse. A city like this”—he gestured vaguely toward the porthole and the fog beyond—“ports, workers, immigrants, crime, shadows… it is a banquet.”

“You sure it’s him?” I said. “Not some copycat? Some nut dressed up with the right fairy story?”

Van Helsing reached behind him, into a satchel. He brought out a folder stuffed with papers. Photographs slid loose. Black-and-white shots, grainy, blurred. Coroners’ tables. Pale faces with dark, neat wounds at the neck. Another, older photo, sepia and warped: a big man with cold, handsome eyes and a mouth that didn’t care for smiling.

“The police in Amsterdam were kind enough to let me see the bodies,” he said. “The stigmata are his. The blood work is… interesting. And then there is this.”

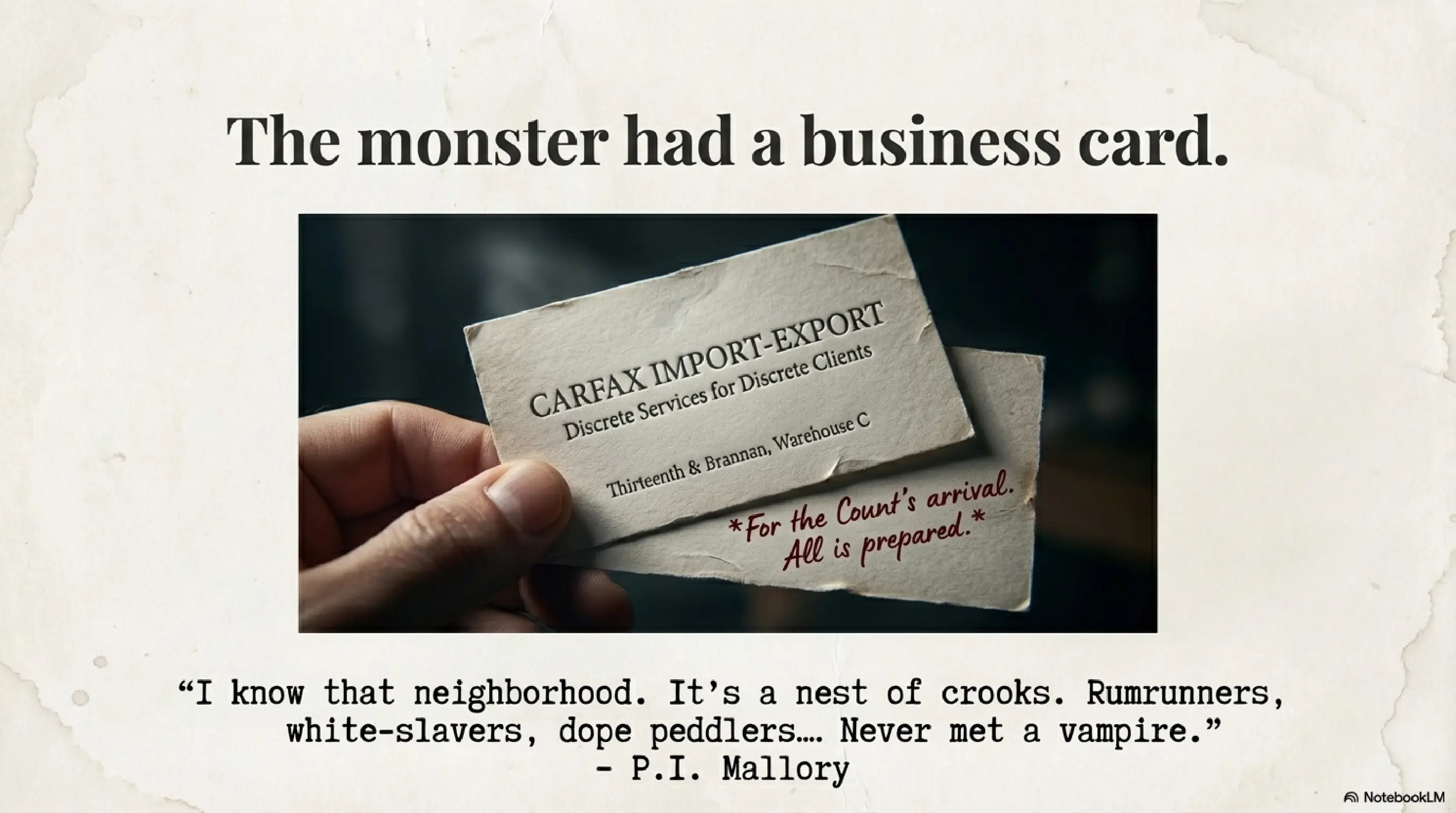

He handed me a small, crinkled card. It was a business card, in fact. San Francisco address. Embossed letters, trying too hard.

CARFAX IMPORT-EXPORT

Discrete Services for Discrete Clients

Thirteenth & Brannan, Warehouse C

On the back, in a slanting, foreign hand: For the Count’s arrival. All is prepared.

“Interesting,” I said.

“Yes?” His eyes were on me like drills.

“I know that neighborhood. It’s a nest of crooks. Rumrunners, white-slavers, dope peddlers, you name it, they’ve rented space there. Never met a vampire. Met a few men who might qualify on a technicality, but they still cast a shadow.”

“You think I am a senile old man chasing a story,” he said, not angry. Just saying it, the way a doctor says, “You have a fever.”

“I think,” I said, “that a Dutch professor flies across an ocean chasing a corpse he swears he killed thirty years ago, and the first thing he does is look up a private dick instead of the cops. That tells me he expects the official boys to laugh him out of the station. That means what you’re bringing me is either very big, very crazy, or both.”

He chuckled, low. “Both is most likely, yes.”

“You want to hit this Carfax place?” I asked. “See what’s inside.”

“Yes,” he said simply. “Tonight, if we can. The longer he has to settle, the deeper he puts down his hooks. In people. In the city.”

Mina’s hands knotted in her lap. “Uncle—”

“Child.” He put his hand over hers. “I am sorry to drag you again into this darkness, but it comes whether we open the door or no. Better we see where it goes, yes? Better a light, even a small one, than to sit in the dark and hope there is no wolf in the room.”

“I’m coming,” she said.

“The hell you are,” I cut in. “This isn’t a church picnic, Miss Harker. If there’s a criminal outfit out there using dead men to put fear into the suckers, they’ll have real guns, real knives. Nobody’s biting necks; they’re just making it look pretty for the papers.”

Van Helsing gave me a look that had too many funerals in it. “You speak of knives,” he said. “You have not seen teeth used properly.”

“Doc, I’ve seen plenty of teeth used in bars on Saturday night. They don’t scare me.”

He sighed. “You are like Jonathan,” he said to Mina, with a sad little tilt of his head in my direction. “The same. Brave, and stubborn, and with a faith in the limitations of evil that is… how do we say… touching.”

I put out my cigarette and stood. “Whether the devil’s wearing silk or cheap wool, we ought to at least knock on his warehouse door. You two stay behind me and do what I say. That’s the deal.”

Mina rose, squaring her shoulders. “We’re wasting time. Let’s go see a vampire, Mr. Mallory. Or a killer who thinks he is one. Either way, someone’s bleeding for it.”

Carfax turned out to be one of those brick tumors growing out of a bad part of town. No windows worth talking about. A big sliding door at the front with a padlock on it that probably cost more than my weekly take. The street was dark and empty. The fog pooled in the gutters. A mutt with one eye watched us from an alley and decided we weren’t worth the fleas.

“Nice place,” I said. “Real welcoming.”

Van Helsing hefted his bag, which clinked ominously. “He likes old places. Places that have history soaked into them. Blood, sweat, tears. They make good soil. For roots.”

“Roots,” I said. “Sure. You two stay back. Let me see if anyone’s home.”

I moved forward, quiet as a man my size could manage in city shoes. The lock was new, but the hasp it sat on was old and tired. I palmed my little friend from my coat pocket—a short, mean piece of steel that had helped me out of more than one tight fix. Thirty seconds of gentle persuasion and the hasp decided retirement sounded nice. The lock and its scrap of metal fell into my hand.

I slid the door up a foot. The breath that came out was cold and smelled like dust and old wood and something under it that I didn’t want to name.

“Stay close,” I told them, and ducked inside.

Warehouse C was exactly what the sign promised: a big, empty cavern stacked with crates. Some marked with shipping stamps from Europe. Some plain. There was a small office up a flight of iron stairs, its frosted window glowing faint amber from a single lamp. No sound except our breathing and the gentle tick-tick of water somewhere.

I put my hand on the butt of my .38 and we climbed.

At the top, I pressed my ear to the office door. Nothing. I tried the knob. It turned easy. Too easy. The kind of easy that says, “Come on in. We’ve been expecting you.”

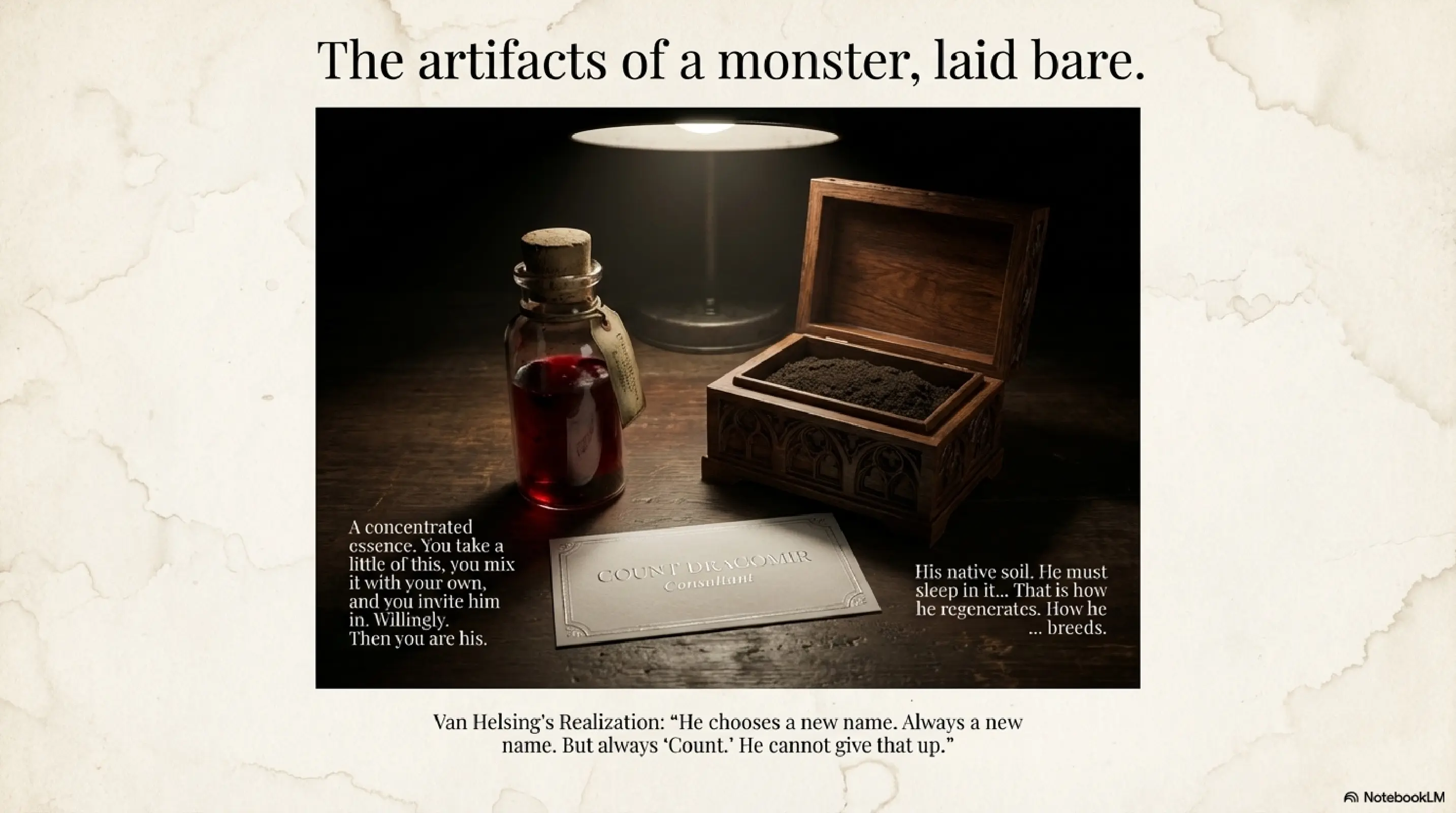

The office was small and neat. Desk with ledgers. Chair. Safe in the corner. Smell of cigar smoke and cheap cologne. And on the desk, laid out just so, were three objects.

- A little wooden box.

- A small glass vial half-full of what looked like dark red ink.

- And a calling card.

I moved closer. The card was good stock, embossed in silver.

COUNT DRAGOMIR

Consultant

—no address, no number. Arrogant, or crazy. Maybe both.

“Dragomir,” Van Helsing breathed. The name came out like he was spitting something bad-tasting. “He chooses a new name. Always a new name. But always ‘Count.’ He cannot give that up.”

“The vial,” Mina whispered.

I picked it up. The stuff inside clung heavy to the glass. When I tilted it, it moved slow, viscous. Under the lamp it wasn’t red. It was too dark. Ruby black.

I don’t know why I did it. Curiosity again. The thing that kills cats, sometimes men. I uncapped it and took a sniff.

The smell hit me like a fist made of every bad memory I’d ever poured rye on. Copper and salt and something older, iron wagon wheels on stone, horses screaming, knives in the low dark. It was blood. Of course it was blood. But it was blood with its Sunday clothes off.

I swayed and gripped the desk.

“Careful,” Van Helsing snapped, moving forward. He snatched the vial from me and recapped it in one sharp motion. “You do not play with such things.”

“What is it?” My voice sounded a little hoarse in my own ears.

“A piece,” he said. “A seed. A concentrated essence. You take a little of this, you mix it with your own, and you invite him in. Willingly. Then you are his. Thrall. Slave. Vampire in training, perhaps.” He looked grim. “Men always want a shortcut to power. He gives it to them. For a price.”

“So he’s running a racket,” I said, trying to shake off the fog in my head. “Selling bottled damnation to the local tough guys. Makes them feel immortal.”

“And makes him strong,” Van Helsing said. “Each one a socket he can plug into. Each one a wire. Do you have electricity, yes? When I was a boy we had candles, now—” He broke off. “Never mind. He is not here. He is still careful. Cautious.”

“He left you a note,” I said, showing him the card. “You’re not the only one who can be dramatic.”

Mina had picked up the little wooden box. It was light, hinged, carved with something that might once have been flowers and now looked more like bones.

“Should I—?”

“No!” Van Helsing’s shout was sharp enough to cut cheese and fingers. “Put it down. Slowly.” He slipped a glove from his pocket, tugged it on, then took the box himself and eased it open on the desk.

Inside, cushioned on velvet, lay a thin layer of fine, dark earth.

“Dirt,” I said. “I’d complain if I pulled that at the roulette table.”

“His native soil,” Van Helsing murmured. “He must sleep in it, some part of him. That is how he regenerates. How he… breeds.” The old man’s eyes glittered. “He has placed it here. A hidden coffin, in the city’s heart. And he leaves it where we can find it. Why?”

“Maybe he likes an audience,” I said.

The hairs on the back of my neck stood up. Not for anything I saw. For what I didn’t. The silence had gone a shade too deep, like the pause before thunder.

Then we heard it. Down below. Footsteps. Slow. Deliberate. More than one pair. The warehouse door rolled up the rest of the way with a groan.

I slid the office door halfway shut and killed the lamp. The three of us stood in the dark, breathing shallow.

Voices floated up, quiet and accented. Not the soft burr of Dutch, not the hard bark of German. Something else. Balkan, maybe. I’d busted enough cheap hoodlums from enough ports to recognize the music if not the words.

“Stay back,” I whispered, drawing the .38. “If this is just a gang using Fairy Tales, a little lead goes a long way.”

“And if it is not?” Van Helsing whispered back.

“Then we’re all about to learn something new.”

Shapes moved below. Two men, maybe three, flashlights cutting thin spears through the dark. One of the beams licked up the metal stairs. They started climbing.

My mouth was dry. The gun felt too light in my hand.

They came slow. One step. Another. The metal groaned. A silhouette took shape in the frosted office glass. Tall. Broad. The kind of man who fills a doorway without trying.

I stepped to the side of the door, back against the wall. My pulse counted off the seconds.

The knob turned. The door edged inward, just enough to let a man see a slice of room. The figure on the other side took one more step.

I moved then. Fast. Old instincts, not as rusty as I’d thought. I grabbed the wrist, yanked, jammed the .38 into his ribs.

“Easy, pal,” I growled. “One wrong move and I ventilate you for free.”

He laughed.

It was a soft, deep chuckle that didn’t go with the accent I’d heard below. It didn’t go with America at all. It came from deep in his chest and rolled out like smoke.

“My friend,” he said, in English as smooth as oiled silk, with the barest trace of the old country stretched across it like a spider’s web. “You think you have a gun. How very charming.”

The flashlight clattered from his other hand and rolled, casting crazy shadows. It lit his face for just a second.

I’d seen it in the photograph in Van Helsing’s file. I’d seen it in my nightmares, apparently, because my blood went cold like it recognized him from somewhere older than my own memory.

Handsome. That was the first thing. The kind of handsome that makes women forget what their mothers told them about not talking to strangers. High cheekbones, straight nose, eyes so dark they swallowed the light. His hair was black and glossy and pulled back from a widow’s peak like a cliché.

But it was the eyes that held me. They were too bright. Too still. Like he was carved from something colder than flesh and just pretending at warmth.

“Count,” Van Helsing said softly.

“Professor,” the Count murmured, not taking his eyes off me. “You look… reduced. Age has not been kind. Or perhaps it has. After all, you are not in the ground.”

Mina made a sound in the back of her throat.

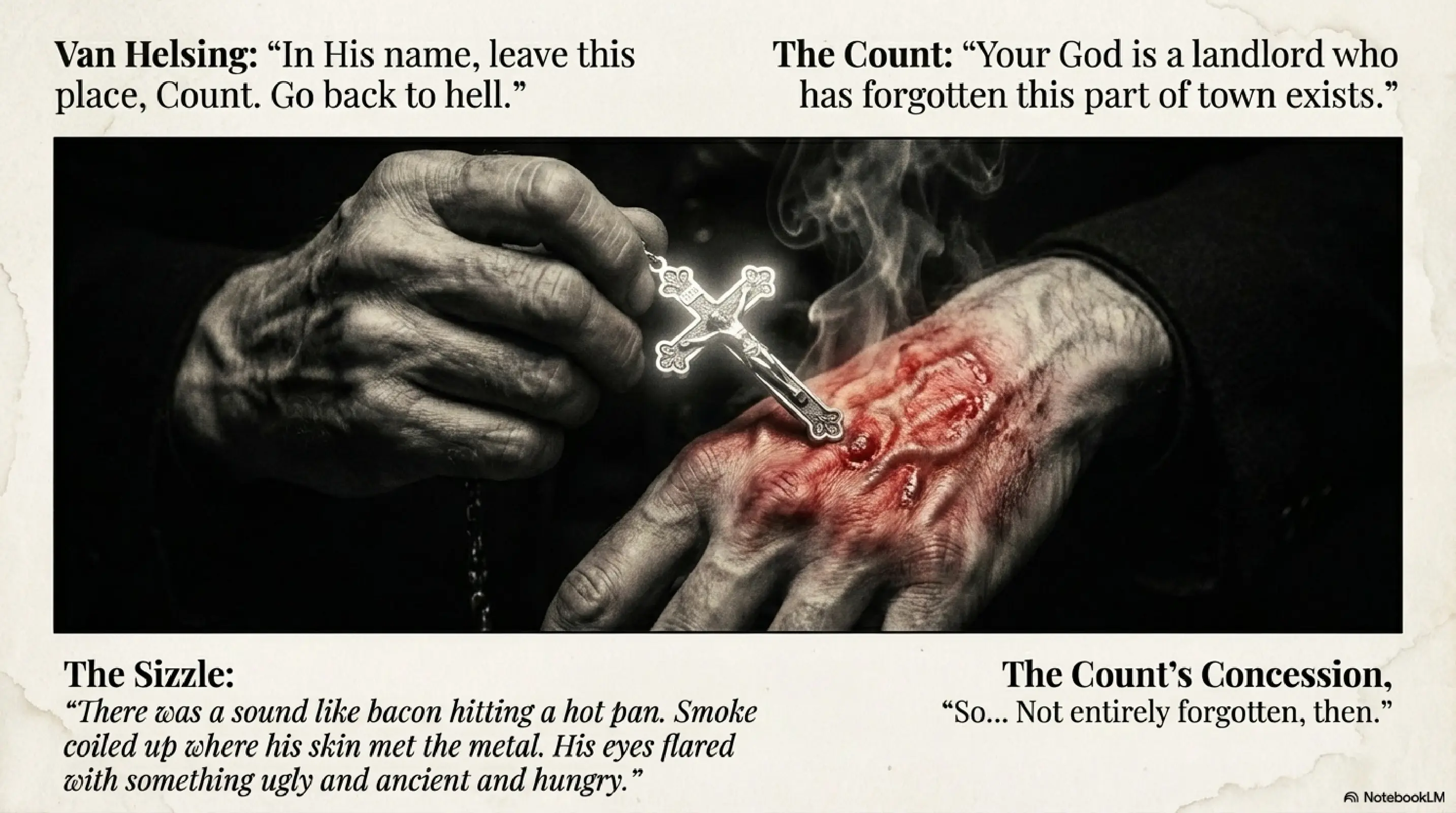

“You leave the girl alone,” Van Helsing said, stepping up beside me. His hand dipped into his bag and came out with something small that glittered. A crucifix, maybe. A little silver cross.

The Count’s gaze flicked to it, then back to the old man’s face. He smiled wider, showing a lot of teeth. Too many, maybe. I told myself that was nerves talking.

“Still with your toys, Abraham?” he said. “Still with your little talismans and your old wives’ tales. The world has moved on. The age of faith is… how do they say? On the skids.”

“Some things do not change,” Van Helsing said, voice steady. “The cross is not a toy. It is a sign. You know this, or you would not bother to mock.”

The Count took one step into the room. Slowly. My gun was still pressed against his ribs. I squeezed the trigger.

Nothing happened.

No, that’s not true. The hammer fell. The gun jumped in my hand. But the sound was wrong. Muffled, like firing into a coat. He didn’t jerk, didn’t grunt, didn’t bleed. He just looked at me with a kind of mild amusement, like I’d sneezed at a funeral.

“You see?” he said to Van Helsing. “Your new world’s weapons. So noisy. So wasteful. So unreliable.”

I yanked the gun back and fired again, straight into his midsection this time. The muzzle flash lit the room. I smelled cordite, hot and sharp. The bullets hit. I know they did. I felt the recoil. But if they did damage, he hid it well. There was no hole, no blood. His coat hung clean and black.

Mina’s breath hitched like she’d been slapped.

My brain scrambled for an explanation the way a drunk scrambles for a cab. I was close enough to see him. To smell him. He didn’t smell like a man. He smelled like cold stone and a dry, dusty room shut too long.

“You will give yourself away, Mr. Mallory,” he said gently. “Guns attract attention. We do not want that. Not yet.”

He moved faster than a man that size should. His hand snapped out and closed around the barrel of the .38. His fingers were cool. They squeezed. The steel creaked. When he let go, the gun sagged in my hand like a candy cane after Christmas.

I took one step back, then another. Some things your mind won’t take, not cold sober or warm drunk. This was one of them.

Van Helsing’s cross was up now, held out at arm’s length, trembling just a little.

“In His name,” he said hoarsely. “Leave this place, Count. Go back to your hole. Go back to hell.”

The Count’s lip curled faintly. “How many times must I disappoint you, Professor? Your God is a landlord who has forgotten this part of town exists.”

He reached out. His fingers touched the silver.

There was a sound like bacon hitting a hot pan. Smoke coiled up where his skin met the metal. His eyes flared, just for a second, with something ugly and ancient and hungry.

He jerked his hand back.

The burn was there. Real. Angry red, already blistering.

“So…” he murmured. “Not entirely forgotten, then.” His gaze slid to Mina. He smiled, slow and intimate. “Ah. The blood remembers. Little Mina. You have grown. Your mother’s eyes. Your father’s stubborn chin. You carry them both so well.”

She drew herself up, white-faced. “Stay away from me.”

“You invited me, my dear. You came out into the dark. How could I refuse such a polite summons?” He looked back at Van Helsing. “You bring children to fight me now, Abraham. Is this kindness? Is this what you have become?”

“They are not the children,” Van Helsing said hoarsely. “You are. Always hungry. Always whining. Always taking. You will find, this time, we have learned new tricks also.” His other hand slipped into his bag and came out with something else. A small bottle, a sprig of something pale and pungent—garlic—and what looked like a sharpened length of wood wrapped in cloth.

The Count’s gaze darted to the wooden stake. For the first time, a shadow of something like wariness crossed his face.

“Ah,” he said softly. “Again with the carpentry.”

“We did it once,” Van Helsing said. “We do it again.”

“You did it to a shadow,” the Count replied. “A piece. Not the heart, Abraham. Never the heart. You were too sentimental. Too bound to the idea of him as a man. That is why you lost.”

Their words slid off me like rain off a slicker. I was staring at the bend in my gun. At the faint, smoking welt on the Count’s hand. At the way the cross had sizzled when it touched him.

Belief is a funny thing. It’s not a switch. It’s a crack in a dam. First there’s just a little dark line. Then a thin spray. Then the whole thing gives way, and the river comes roaring through.

Downstairs, another voice called up in that foreign tongue. Worried. The Count raised his chin slightly.

“Yes, yes,” he called back. “I am finished. Close everything. Prepare the crates. We work before dawn.”

He took two steps backward, into the hall. For a second, he was framed in the doorway, a tall, dark slice of something the world had tried to forget.

“We will meet again, Mr. Mallory,” he said. “You have a certain… flavor. Courage, they call it. I call it spice. Do not waste it on bullets.”

He inclined his head to Mina. “Sleep well, little one. Dream sweet. I will be there, at the edges, waiting.”

Then he was gone, moving down the stairs with that smooth, impossible speed. We heard the mutter of voices, the slam of the big door, the rattle of the lock. Then nothing but our own ugly, ragged breathing.

My knees wanted to fold. I made them stay straight.

Van Helsing set the cross down on the desk with great care. His hand was shaking.

“You see now, Mr. Mallory,” he said quietly. “Why I bring you in. This is not a case you can take to the police and say, ‘Arrest this man, he is a corpse that walks and does not bleed.’ But it is a case. A crime. Old as the world. He steals life. That is his profession.”

I flexed my fingers around the twisted gun. “I put two slugs into him,” I said. “Point-blank.”

“Yes,” Van Helsing said. “And you proved to yourself what I could not make you believe with a hundred words. The dead do not die so easy.”

Mina moved to the window. Her shoulders were hunched. I could see her reflection, faint and wavering, in the dirty glass. There were tears on her cheeks she hadn’t noticed.

“He knew my parents,” she whispered. “He remembered them. He remembered me.”

“Evil has a good memory,” Van Helsing said softly. “It must. It holds grudges.”

I holstered the ruined gun out of habit. Useless. Just weight now.

“All right,” I said. “He’s real. I’ve seen ghosts in alleys before, but they were always made of gin. This one bent steel. So he’s real. What’s the play?”

Van Helsing looked up at me, and for the first time since I’d met him, there was a glint in his eye that looked a little like hope.

“The play, Mr. Mallory,” he said, “is that we do what we have always done. We hunt. We find his lairs, we destroy his soil, we cut off his lines of power. We turn his disciples. We burn him wherever we can reach. And at the end, when he is cornered and desperate, we drive a piece of wood through the black thing in his chest he calls a heart, and we make sure this time that there is nothing left. No shadow. No drop of blood. Nothing.”

“And if we fail?” Mina asked quietly.

He was silent a moment.

“If we fail,” he said, “then this city becomes one long, slow night.”

I looked past them, out at the water-stained wall, and saw the city in my mind. The lights. The people. The drunks and the rich, the whores and the priests. I thought of all that blood, walking around on two legs, not knowing some old nightmare from across the ocean had just moved into a brick box down by the wharf.

“I never liked this town much,” I said. “But I’ll be damned if I let a foreigner come in and drink it dry without paying local tax.”

Van Helsing’s mouth quirked. “Then you are with us?”

“I’m in,” I said. “But I’m putting it on the books. Abraham Van Helsing. One count of murder. Several hundred counts of attempted. Accessory to supernatural. I’ll need a bigger filing cabinet.”

Mina turned from the window. Her eyes were clear now. Harder. The girl who’d walked into my office that afternoon had believed in fairy stories only halfway. The woman standing here had met the wolf with his mask off.

“What do we do first?” she asked.

Outside, somewhere distant, the city’s clocks began to strike one. A lonely, solemn sound, counting out the time left until dawn.

Van Helsing picked up the little box of earth. His fingers tightened on it.

“First?” he said. “First, we deprive our Count of his comfort. We salt his beds. We burn his cradles. Come, Mr. Mallory. You are a detective. You know how criminals think. This one is very old, but he is still a criminal. We start with what we know.”

He looked down at the black soil, then back up at me.

“We start,” he said, “with the dead.”

NotebookLM

NotebookLM generated a nice infographic …

… and an interesting analysis …

The analysis by NotebookLM highlights some interesting points:

- the story “masterfully fuses two completely different genres into one totally unforgettable story.”

- the story creates two worldviews — noir skepticism vs. Gothic metaphysics — and lets them collide: “These two opposing worldviews are on a collision course.”

- Ending with a thematic question is a classic literary device: “When a man who only believes in bullets teams up with a man who believes in crosses, who really has to change more?” This is meaning-making, not just storytelling.