They called me Billy Bones

February 05, 2026

A dying pirate’s confession, told in rum and regret. Billy Bones recalls Flint’s last breath, the cursed map he should have burned, and the boy at the Admiral Benbow who reminded him of someone he’d rather forget.

They called me Billy Bones.

That wasn’t my name, not the one my mother gave me or the one the clerk scratched down when I signed on my first ship, hands shaking like a sinner copying Scripture. But after a while a man’ll answer to whatever folks shout when they’re putting a knife in him or sliding a bottle his way. You keep fighting about names and you won’t have time for the real things—like who’s behind you and how far the drop is when the rope snaps taut.

So Billy Bones I was, and Billy Bones I died, or near enough.

I came ashore at that little hole they called the Admiral Benbow because I was tired. Tired in the bones, in the liver, in those little nerves that keep watch for you even when you’re drunk as a lord and pretending you sleep like a baby. You get to an age where your enemies don’t scare you so much as your memories do, and the only way I knew to shut them up was rum and distance. And I’d had enough of the first and not near enough of the second.

The Benbow was a quiet sort of place. A coast road with more mud than people, the gray sea out front, and a set of cliffs behind like a bad conscience that wouldn’t go away. One window, one door; you could see trouble coming. I liked that about it.

The boy was there, Jim. Skinny kid. Big eyes. Thought he could see straight through a man. A lot of folks think that, first time they look at me. They see the coat, the scars, the way I carry my head like I’m still leaning into a gale. They don’t see what I’ve put behind my back.

“More rum,” I told the boy the first night. My voice came out rough, like it had been hiding under the keel too long. “And cheap. I’ll know the difference.”

He brought it. Polite, scared. He reminded me of another boy, from long back, off Cartagena. I’d thought about knifing that one. Didn’t. I was young then. Still believed in lines I wouldn’t cross. Funny thing about lines, though. You circle ‘em long enough, you find out they’re only chalk on the deck and the sea washes everything clean.

I paid up front. Slapped my broad hand on the table and let the coins talk for me. Not the good ones. Not Flint’s kind. None of the Spanish gold with the faces and the holes of dead men behind ‘em. Just ordinary money. Honest money.

That’s what I told myself, anyway.

The first night, the old man that owned the place came sniffing around. Sickly fellow. Cough that sounded like a cannon ball rolling around in a rotten barrel.

“We don’t get many seamen here, sir,” he said. “Quiet spot, this.”

“Good,” I said. “I want it quiet. A room, food, and rum. And…” I looked at the boy. “And you keep an eye out for me, lad. Tell me if you ever see a seafaring man with one leg. You’ll know him if you see him. You tell me quick, and there’ll be a silver fourpenny in it, every month. That’s honest.”

I said “honest” the way a drunk priest says “Amen.”

The boy nodded. I could see the coin glinting in his brain already. It bound us, that little promise. You share money with a man, you share fate. You share it with a boy, you convert him.

After that, I settled in.

I took my meals in the corner that watched the door and the sea both. I kept my back tight against the wall, my cutlass within easy reach. They didn’t like that, the woman and the sick old man, but they liked the money, and money talks louder than manners.

I’d drink till the world got kind of soft around the edges. And then, sometimes, I’d sing. Not loud. Just under my breath, the old tune that clung to us like the stink of powder and spoiled meat:

Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest…

The boy heard me once. He froze in the doorway, holding a tray, and his eyes got wide. I saw something flash there, something I didn’t much like. Curiosity. That’s the first step towards damnation, if you never heard the sermon anywhere else.

“Where’d you learn that, lad?” I asked him.

“Nowhere, sir,” he said. “It’s just…I heard it once from a sailor in town.”

“Liar,” I said, and smiled so he’d think I was joking. “That song don’t travel alone. Men carry it. Men like me.”

I should’ve shut up then. But that’s the trouble with rum. It holds your tongue for you and turns it loose when you ain’t watching.

“That song,” I said, “belongs to a man named Flint.”

I hadn’t meant to say his name. Even sober, I wouldn’t. There’s a handful of names you don’t let out in friendly company. Flint. Pew. Silver. For different reasons, but the same end. You say ‘em enough, they come.

The boy leaned in close, like a moth to a lantern that doesn’t know about fire.

“Who was he?” he asked.

“A captain,” I said. “The best there ever was. Best meaning worst, if you take my meaning. Flint sailed with the devil and sent him home short-handed. That was his way.”

I could see it all, then. The heat. The sweat. The way the sun hit the water like a musket flash that never ended. Flint on the quarterdeck, his eyes as dead as cannonballs, his mouth soft and lazy as if ordering another round instead of another broadside. Men begging, screaming, splashing. The black flag flapping above us with that stiff little snap-snap sound, like bones knocking together.

I remembered the way he’d looked at me once, when I brought him the account book. Neat line of figures. Neat little crosses where the ships had gone down.

“Bones, my fancy,” he’d said, and clapped my arm. The same arm that had the gallows tattooed into it later. We were sober when we put that on. That should tell you something.

“That day’s gone,” I told the boy. “There’s no Flint no more. Just his…shadow. On men what sailed with him.”

He looked at my arm then. At the ink. At the gallows and the little man hanging there, neat as you please.

“Prophetic, that,” the doctor called it, later. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I stayed at the Benbow longer than I meant to. Once you run far enough, you forget what it is you’re running from. Your legs get used to the motion. Your heart don’t. It just keeps thumping, waiting for the door to open.

Sometimes, standing on the headland, watching the gray water roll and hiss, I’d touch my breast where the oilskin packet lay flat and hard under my shirt. I could feel the edges of the folded map through it. Flint’s treasure. Flint’s pile, in my hand.

Not that I stole it.

Not at first.

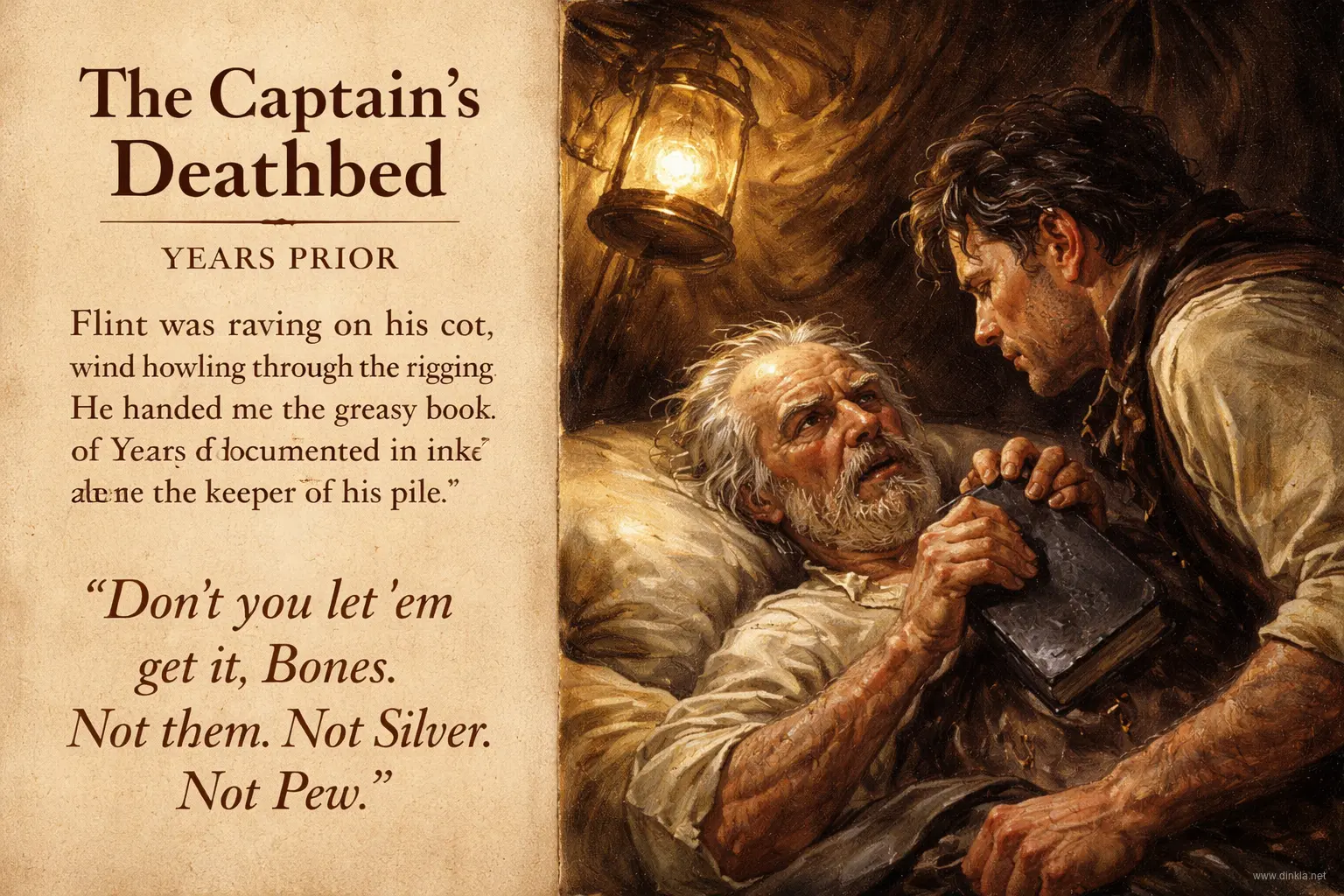

Like most evil things, it didn’t feel like stealing when I did it. We were all drunk, those last days. Flint worst of all. He’d been bleeding inside for years and the liquor just opened the flood-gates. He was raving on his cot in the cabin, the wind howling through the rigging, the men whispering together like rats in the hold.

“Bones,” he croaked. “My fancy. Come here.”

I went in alone. That’s how it always was. Me and him. He trusted me, if a man like Flint ever trusted anyone. Maybe he just liked to see his own ugliness reflected in a face that still had some meat on it.

He held out the book. The leather was greasy from his hands. The ink was smeared in places, but the figures were clear. Years of work. Years of killing.

“That’s it,” he said. “That’s my life there. There’s a chart, too. Don’t you let ‘em get it, Bones. Not them. Not Silver. Not Pew. Not any of ‘em sons of whores. You hear me?”

“Aye, Cap’n,” I said.

He grabbed my wrist. That’s what I remember most. The strength in his fingers, even then. They dug in like fishhooks.

“I buried it,” he said, spitting the words. “My pile. Mine. Not theirs. You keep it safe. Nobody knows the lay but you and me. You… and after you… nobody.”

His eyes rolled back white. He bit at the air. The song came out of him, ragged and wrong:

“Fifteen men… on the…”

Then he died.

As clean as a candle snuffed. One breath he was there, full of hate and rum and iron. Next breath, he was a weight on the mattress and a bad smell in the room.

I remember thinking it was a fair way for a man like him to go. No gallows. No crowd. Just his own words choking him.

I should have burned that map. I should have rolled it up and shoved it into his dead mouth and let him take it down where we all knew he was going.

Instead, I took it.

Not right away. But the seed was there. It sat in my head, quiet, patient. We buried him at sea with the others howling and pretending they were sad and honest. That night, I went back to his cabin. Took the packet and the book. Hid ‘em under my shirt. Felt the weight of it like a new heart that didn’t beat yet but planned to.

I told myself I deserved it more than the rest. I’d been the one at his elbow, watching him stack the gold, counting the crosses. I’d carried his orders out, and worse. Men over the side. Women. The boy off Cartagena. I didn’t knife him, but I held him down. That’s a kind of killing, too.

So I ran, later. When the WALRUS got laid up and the talk turned ugly—the kind of ugly that ends in knives and short ropes on a lonely shore—I took the first chance and slid off by night. Cut my way loose from them and from myself, or so I thought.

That’s how I came to the Benbow. That’s why I watched the road and jumped at every sound. You don’t keep Flint’s secret without paying for it, one way or the other.

It took them longer than I expected to find me. Long enough that the fear got tired and turned into a habit. Long enough for my hands to shake if they didn’t get their share of rum by noon. Long enough for the boy to start to matter.

Oh, I liked the lad. I’ll say that much. He was straight, as boys go. He looked at me like I was a story come to life. A bad one, maybe, but still a story. There’s a way a man gets used to being feared. Makes him feel big. But being admired—that’s a weaker drug and worse, because it makes you forget what you are.

Sometimes I’d think about taking him with me. With the map. Show him how a man can make his own fate with a little ink and a lot of nerve. Then I’d look at his hands, clean and soft, and I’d remember the other boy’s hands clawing at my wrist, and I’d think: no. Not this one.

Anyway, they found me.

It was a raw morning. Wind chopping in off the sea, sky the color of old pewter. I was at my post by the window, my fingers locked around a mug that held more emptiness than rum. The old man was wheezing somewhere in the back. The wife was clanging dishes like she meant to scare the world away.

The door creaked.

He stepped in quiet as a bad thought. Black Dog. I’d know that split face anywhere, that scar curling his cheek like a question he’d never answer.

We looked at each other. All the years between us cracked like a pane of ice.

“Bill,” he said.

“That’s not my name,” I said. But it was.

We talked. I won’t go into it. It was old business, and there’s nothing deader than old business that suddenly sits up and starts breathing. He wanted what all of ‘em wanted. Flint’s secret.

“Silver’s looking,” he said. “Pew’s sniffing. They’ll have it if you don’t share, Bill.”

He smiled when he said “share.” Like he thought it was a joke.

Maybe it was. Maybe I was the joke, sitting there with my trembling hands and my tarnished cutlass and my good intentions about boys I’d never save.

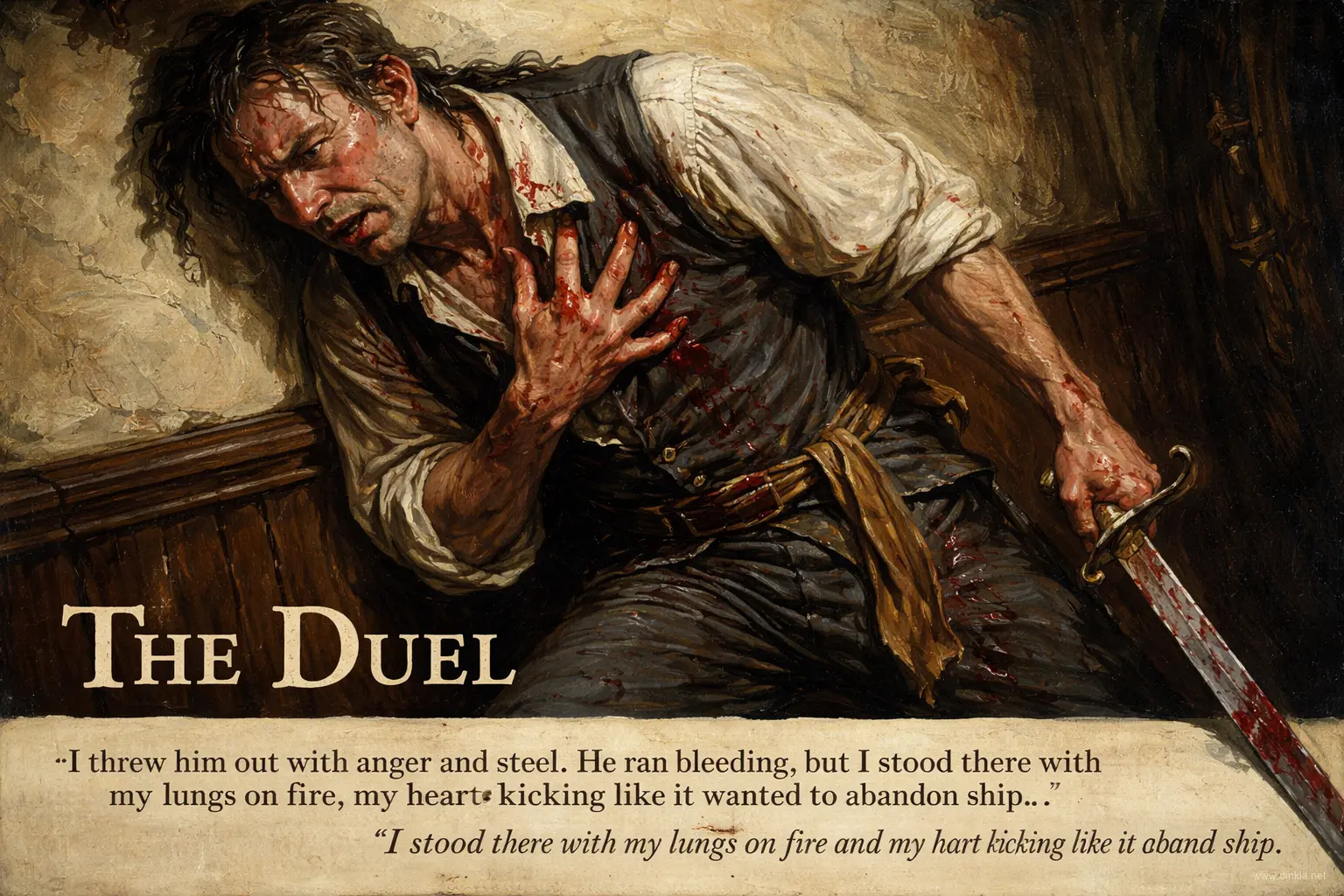

I threw him out. Not clean, not clever. Just anger and steel. The boy saw us, heard us. He watched me like a man watching a fuse burn down.

Black Dog ran bleeding down the road, and I stood there with my lungs on fire and my heart kicking like it wanted to abandon ship.

That’s when it hit me. Not a blade. Not a pistol ball. Just a white hot pain behind the eyes and a hand grabbing my chest from inside. I remember saying, “Rum,” and then the floor was much closer than it had been.

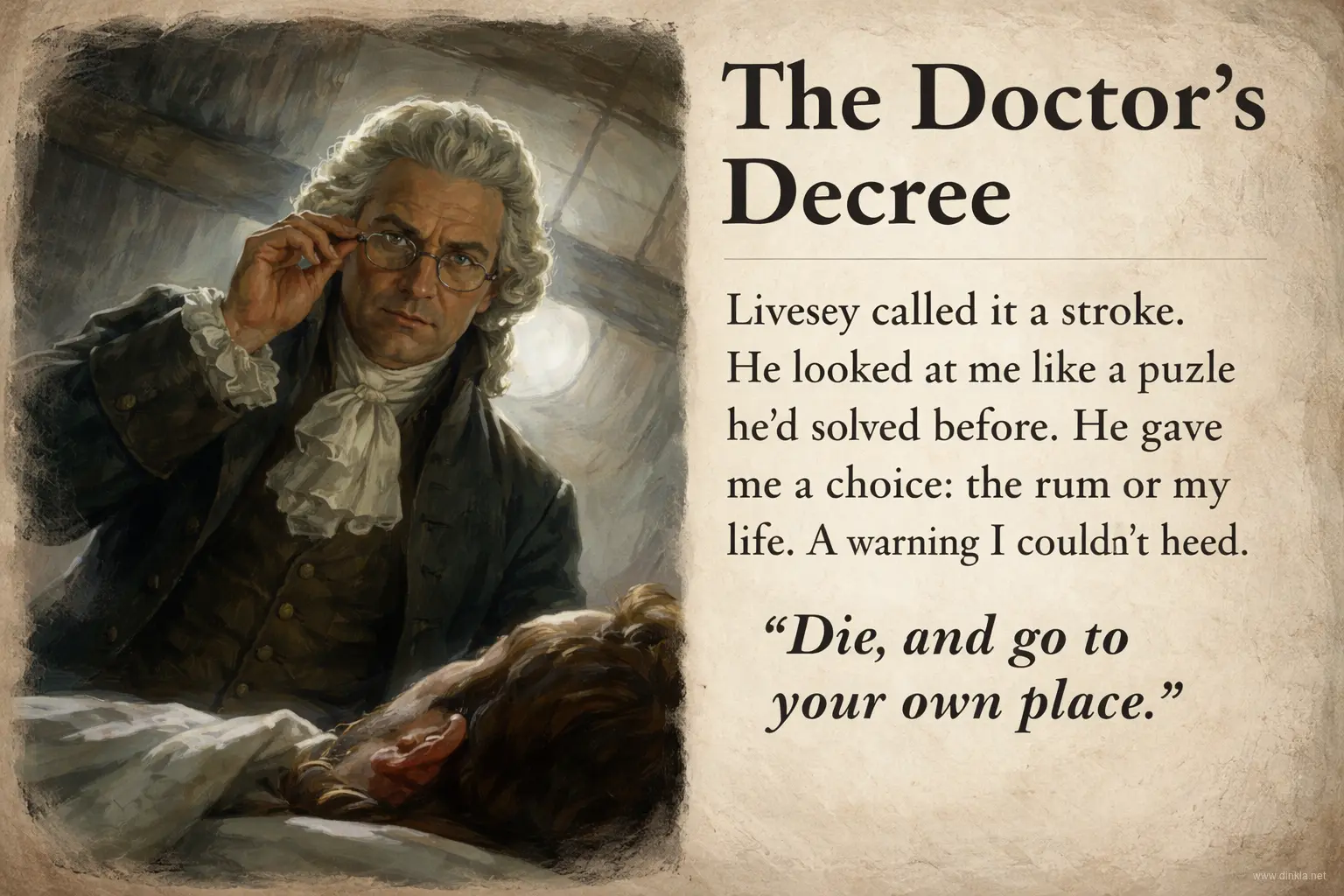

They told me later it was a stroke. The doctor did. Livesey, his name was. Country sawbones in a neat coat, with a neat way of talking like men were puzzles and he’d seen ‘em solved before.

He cut my arm and watched the blood like it was telling him a story.

“Prophetic,” he said, tapping the gallows on my skin.

“Mind your tongue,” I growled. Couldn’t help it. Something about him riled me worse than Black Dog. Black Dog wanted what men like us always want. The doctor…he wanted to save me without knowing what I was. That seemed like a bigger insult.

“One glass of rum won’t kill you,” he said. “But if you take one, you’ll take another, and I stake my wig if you don’t break off short, you’ll die. Do you understand that? Die, and go to your own place.”

“My place,” I said. My tongue felt thick. “Ain’t you a preacher now.”

He helped haul me upstairs with the boy. My body was heavy, useless. I could feel one side of my face sagging like a rotten sail. That scared me worse than any gunshot. I’d seen men like that, mouths dragging, eyes stupid. They weren’t men no more. They were things. Things you left behind when you went ashore.

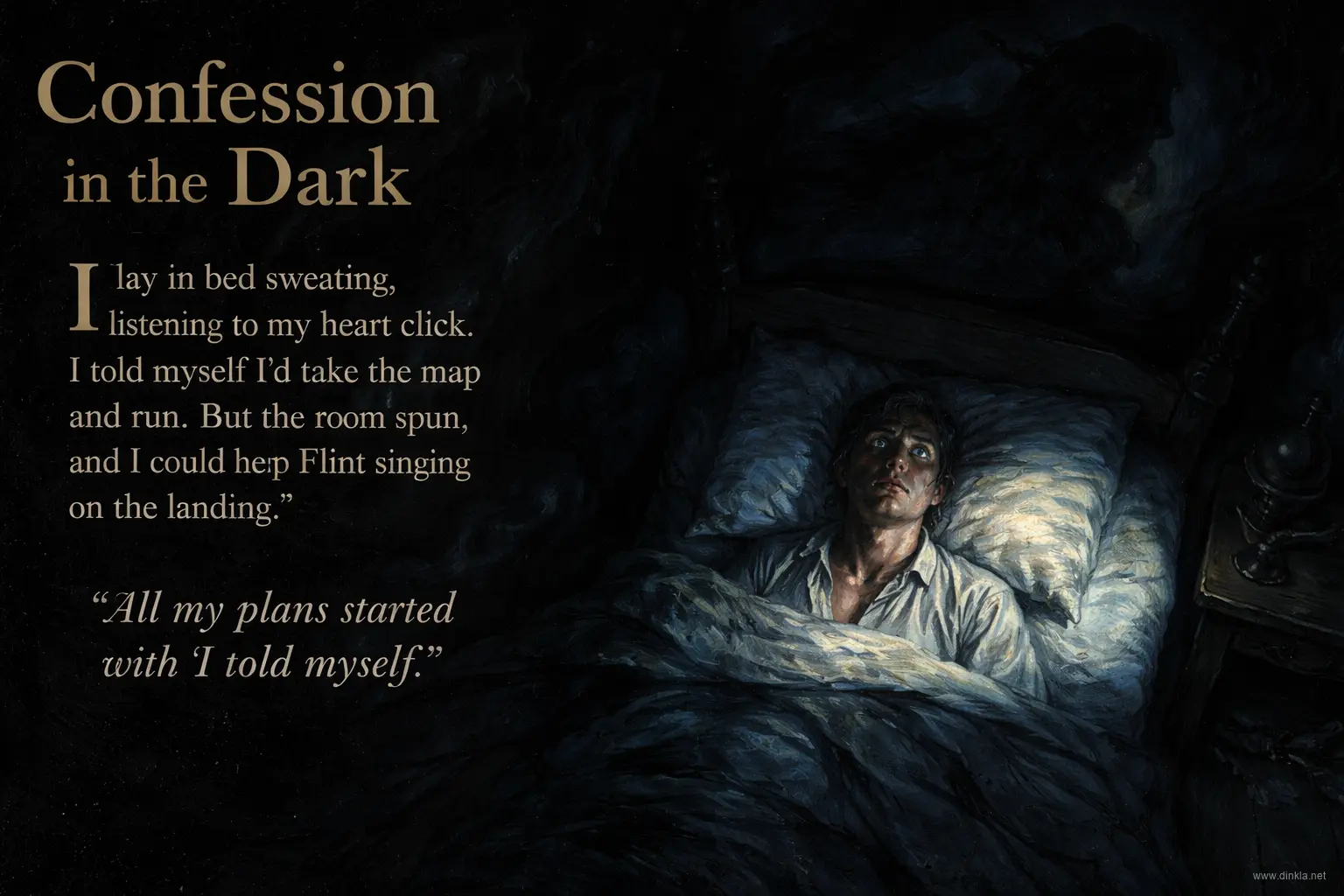

I lay in that bed, sweating and cursing, listening to my own heart click and groan. I told myself I’d cut down on the rum. Get my strength back. Take the map and be off before the others came.

You notice the pattern? All my plans started with “I told myself.”

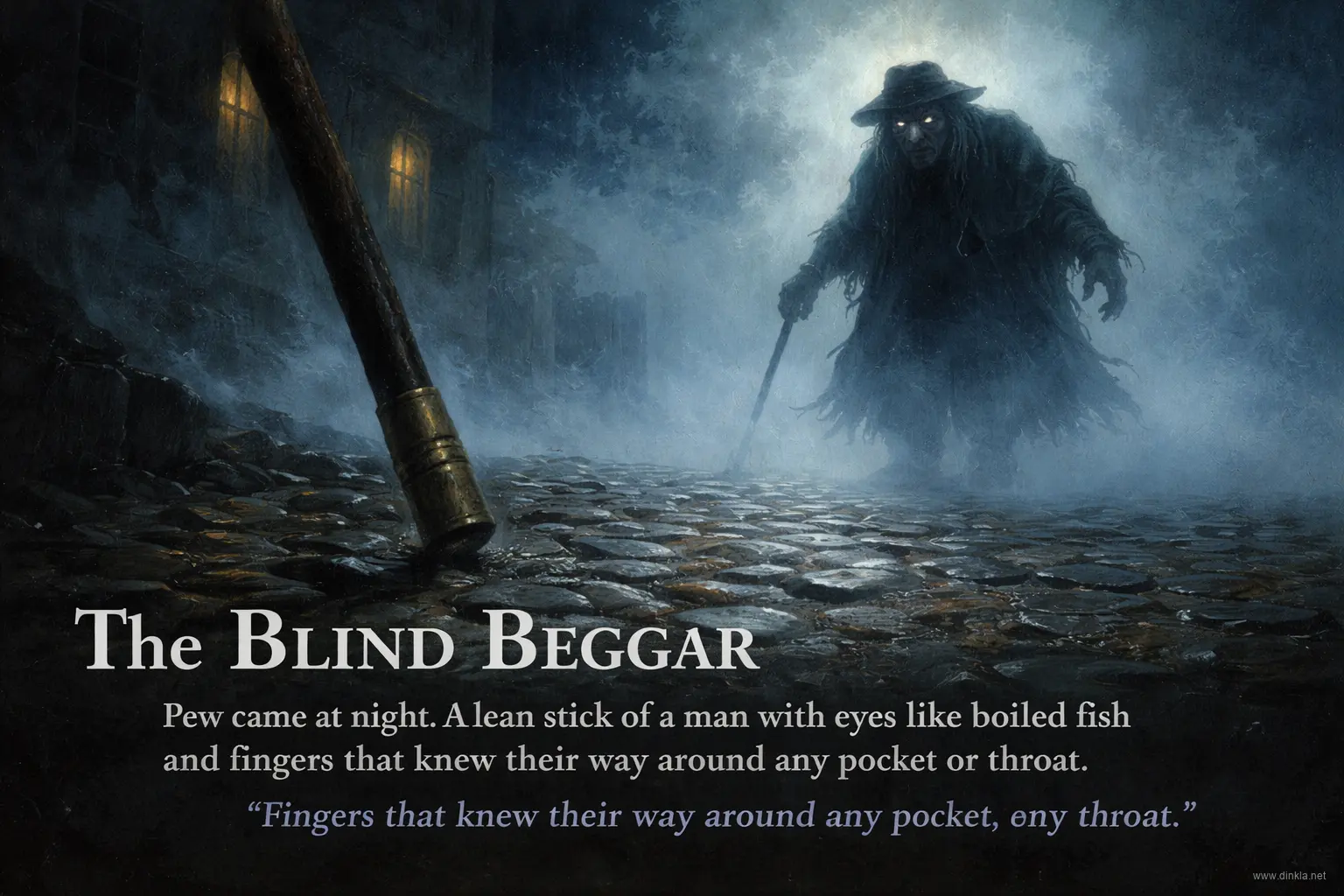

Pew came at night.

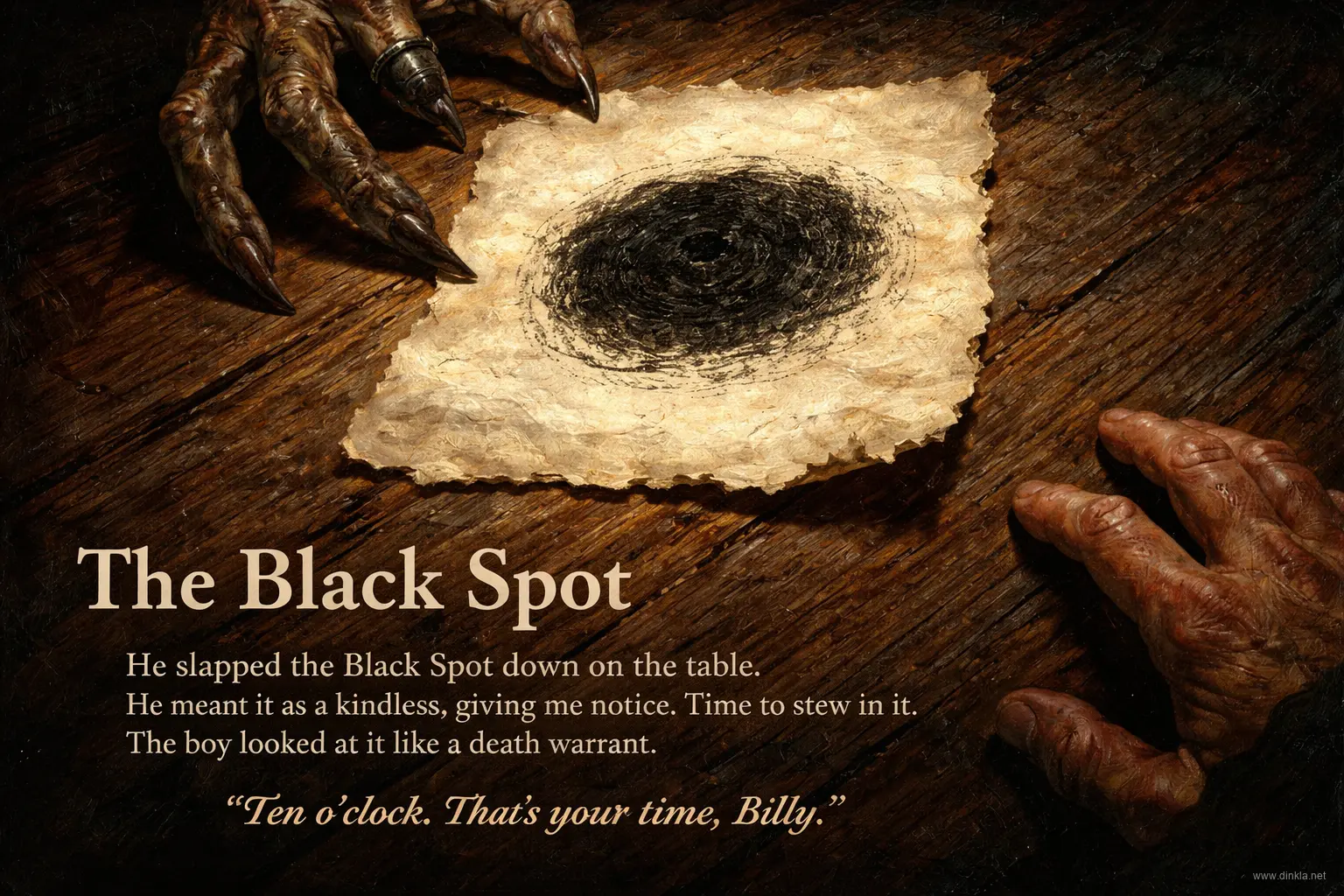

Blind Pew. Lean stick of a man with eyes like boiled fish and fingers that knew their way around any pocket, any throat. He brought the Black Spot with him, neat as you please. Slapped it down on the table in the taproom while the boy shook and the old woman screamed and the old man finally decided to die for good.

“Ten o’clock,” Pew hissed. “That’s your time, Billy.”

He meant it as a kindness. He was giving me notice. Time to stew in it.

Well, I stewed.

The boy came up, wide-eyed, clutching the little round of paper like it was a death warrant. Which it was. I took one look and knew it: the Spot. I’d seen it passed before. I’d watched hard men turn soft at the sight of that smudged black circle.

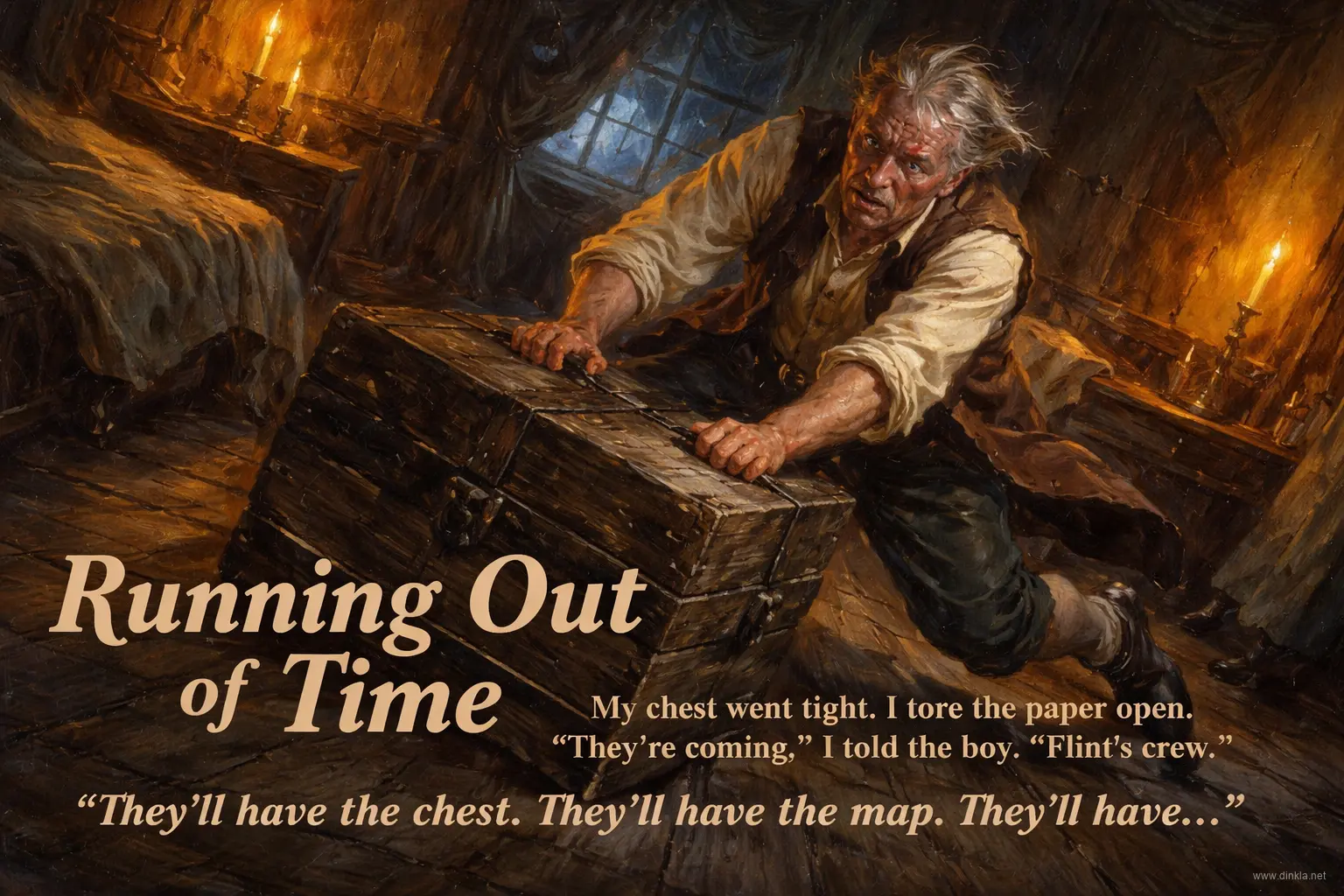

My chest went tight again. The room spun. I could hear Flint singing somewhere, clear as if he was on the landing: Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest… Yo-ho-ho—

I tore the paper open with shaking fingers. There was writing on the back. I couldn’t read it. Didn’t need to.

“They’re coming,” I told the boy. “His crew. Flint’s. Or what’s left of ‘em. They’ll have the chest. They’ll have the map. They’ll have…”

My head felt like it was full of hot sand. My tongue didn’t fit my mouth.

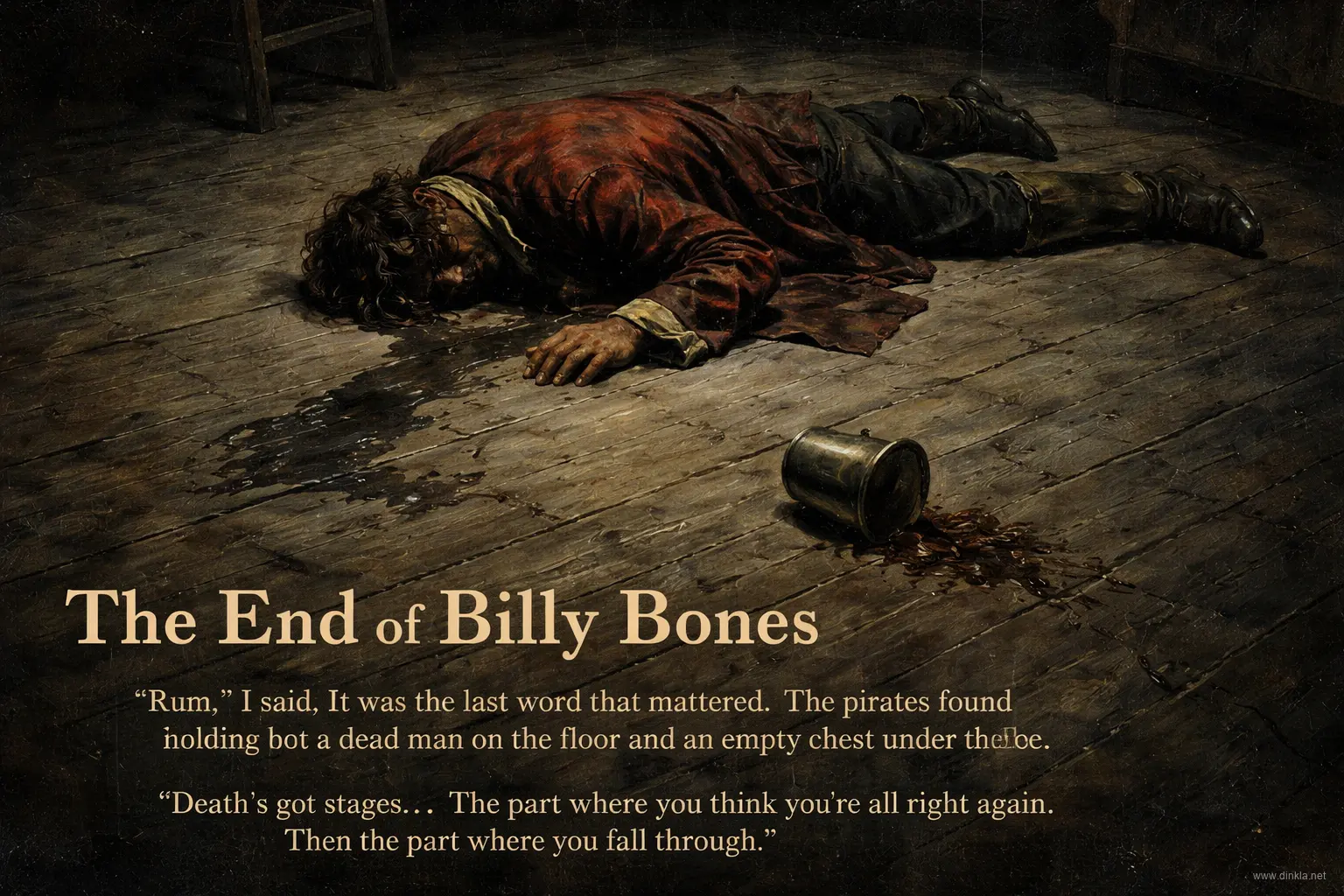

“Rum,” I said again. Maybe the last word I ever said that mattered.

You know the rest, more or less. The pirates came. They smashed and broke and cursed and found nothing but a dead man on the floor and an empty chest under his bed. Empty of what they wanted, anyway.

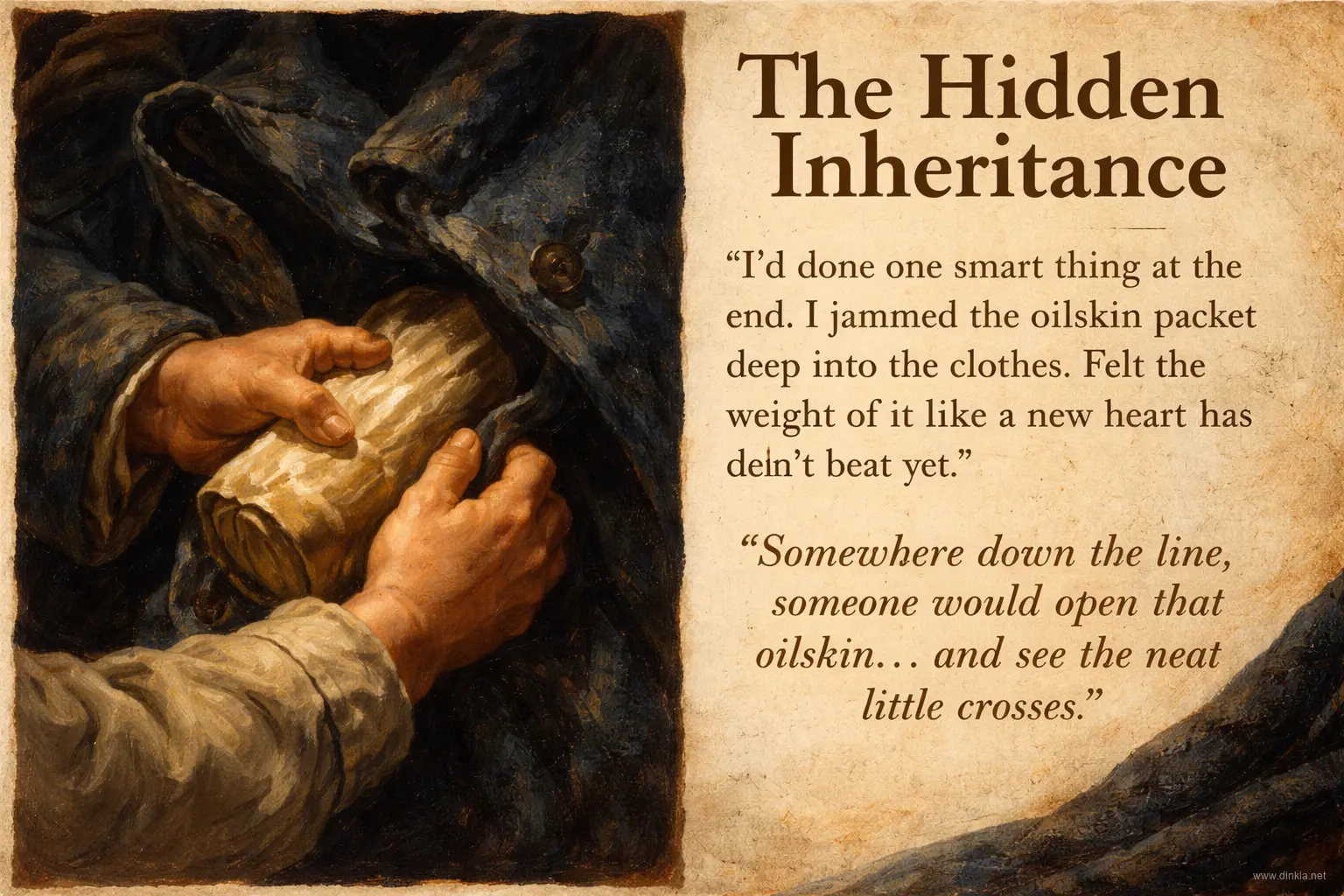

Because I’d done one smart thing, right at the end. The only one.

The boy and his mother left me lying on that floor a while, thinking I was past help. But death’s got stages, same as drinking. There’s the first wobble, the first slip. Then the part where you think you’re all right again. Then the part where you fall through.

While they were rooting in my chest for the coins I owed ‘em, I fumbled under my shirt and got hold of the oilskin packet. My good hand still worked a little. I jammed that packet deep into the clothes at the bottom, between the rags and the seaman’s gear and the things no one ever wears but won’t throw away.

I knew the woman. She’d take the chest, if she took anything. She’d take it for the debts. And somewhere down the line, someone would open that oilskin, and they’d see the map, and the book, and the neat little crosses where all the blood got added up.

That’s my gift to the world. Flint’s gold. His curse. His joke.

I didn’t do it out of kindness. Don’t go thinking that. I did it because I wanted to hurt the ones hunting me. I wanted them to come up hard against a blank wall and feel the kind of sick, helpless rage I’d been dragging around for years. I wanted them to know somebody’d beat ‘em.

I suppose I did, for a while.

So there it is. That’s what I was, and what I did.

Billy Bones, they called me. Mate to Flint. Drunk at the Benbow. The man who carried his cursed secret and passed it on like a disease. I thought I was running from my past, but I was just delivering it to the next generation, special delivery, with interest.

Maybe the boy will do better with it. Maybe he’ll take the map and bring it to some clean-handed squire and some doctor with a tidy soul and they’ll all go off chasing treasure like it’s an adventure and not a ledger of murder. Maybe they’ll tell themselves a story where they’re the good men come to take the bad men’s gold, and maybe they’ll even believe it.

Or maybe they’ll stand over a pile of coins one day and wonder, just for a second, how many planks were walked to stack it that high. How many backs broke. How many hands reached up out of the dark and got stepped on.

Not that it matters.

Gold doesn’t care whose face is stamped on it. The sea doesn’t care whose body feeds it. And justice—well, I never met the man.

All I knew was Flint, and rum, and the feel of that oilskin packet against my skin like a second heart I couldn’t cut out.

They called me Billy Bones.

By the time anyone knew what that really meant, I was beyond caring.

P.S. Generated with Chat GPT 5.2 with high thinking. Images created by own scene description tool and OpenAI gpt-image-1.5. The images were generated with the “low” style, because they look much better in this pirate setting. The atmosphere is much better. There is a Youtube version with an audiotrack generated with 11Labs.