Three Victorian Fault Lines: Reputation, Vitality, and Ontological Shock

January 26, 2026

It started the way these things always start: with paperwork, politeness, and a good man’s name lying out in the open like cash on a butcher’s block—clean until someone decides to cut.

Three Victorian Fault Lines: Reputation, Vitality, and Ontological Shock

The city was running damp and dirty. Not the poetic kind. The kind that turns soot into paste, that carries horse piss and coal ash into the seams of your cuffs, that makes every gaslamp burn sickly because even the air is overworked. I was out late, collar up, thinking the sort of thoughts you can afford only after the clerks have gone home and the streets stop pretending.

I am not a detective. I’m a lawyer. If you do it properly, you don’t chase footprints—you chase signatures, seals, and the small legal fictions that keep men upright. But there are nights when the whole place feels like a case file left open in the rain, and you can’t help reading what isn’t meant for you.

A frightened little story found me in a doorway.

“A brute,” the watchman said. “A small one. But mean as a dock rat. Knocked a child down like it was nothing.”

He didn’t say monster. He said man. That mattered. Monsters you can sell in penny sheets. Men you have to eat beside.

That’s when I first heard the name Hyde. And that’s when the first fault line showed itself.

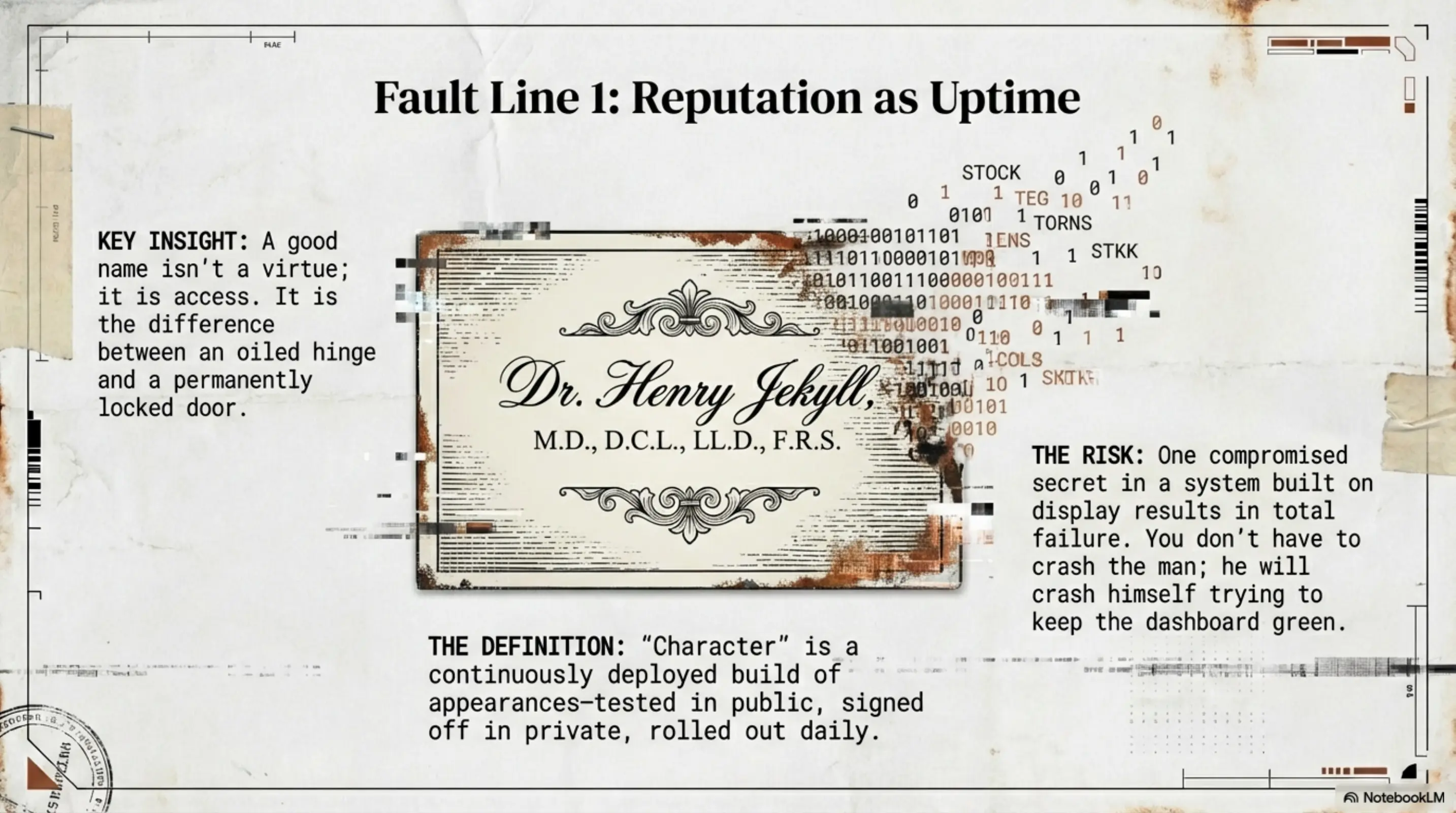

1) Respectability is currency. And it runs on a broken pipeline.

In this town, a good name isn’t a virtue. It’s uptime. It’s access. It’s the difference between a door opening on oiled hinges and a door never opening again. People call it “character,” but what they mean is a continuously deployed build of appearances—tested in public, signed off in private, rolled out daily to anyone watching.

And everyone is watching.

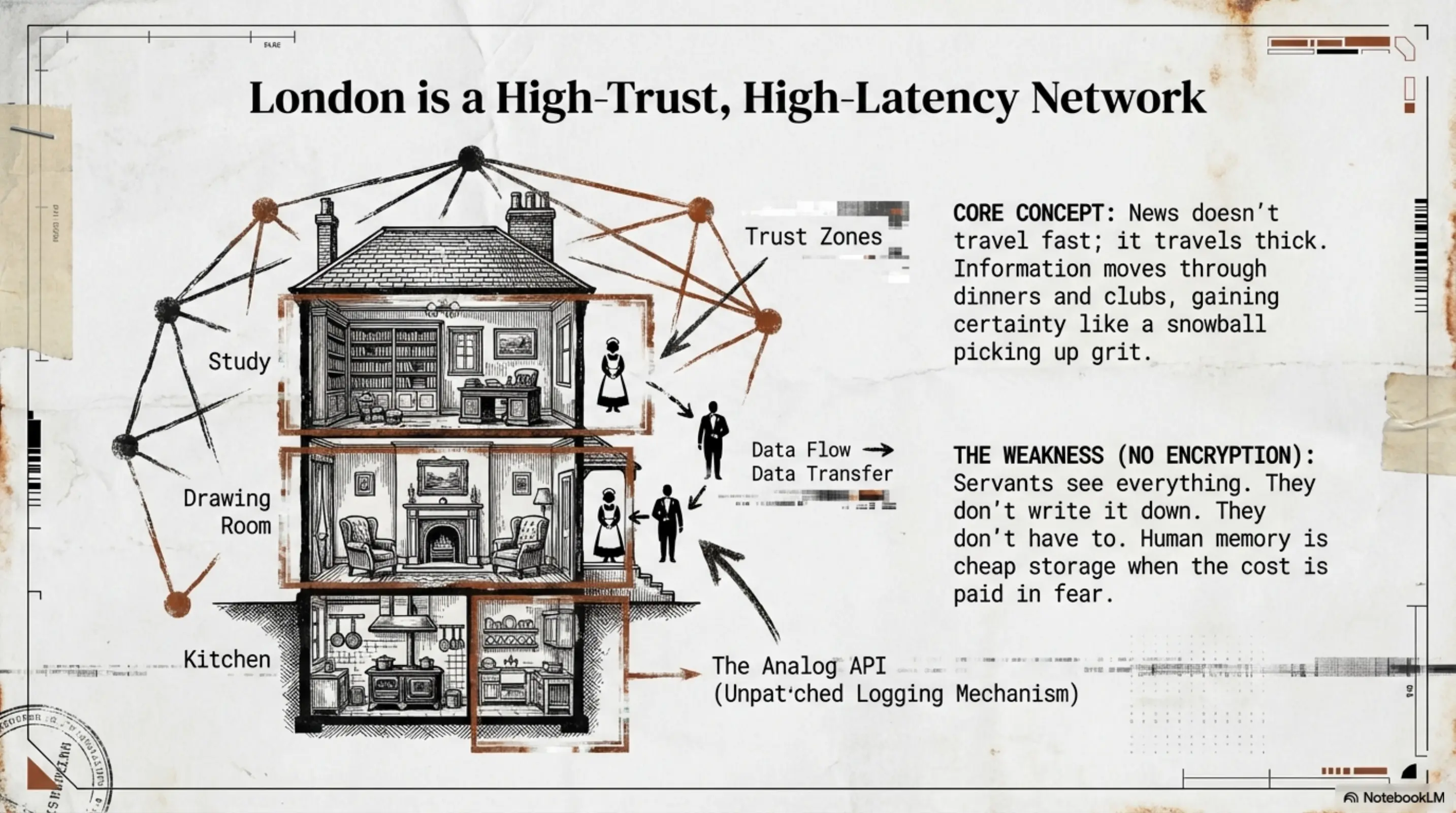

Think of the polite world as a high-trust network with terrible latency. News doesn’t travel fast; it travels thick. It moves through dinners and pews and club corridors and kitchens, picking up certainty the way a snowball picks up grit. By the time it reaches you, it’s no longer information. It’s verdict.

The problem is the system has no encryption.

The servants aren’t just witnesses; they’re an analog API that was never designed, never documented, never patched. They touch everything. They see everything. They move between trust zones with trays in their hands and silence on their faces. They don’t keep minutes; they keep logs—who came in, what time the bell rang, which coat smelled of gin and cheap perfume, which cuff needed blood lifted from it before breakfast.

They don’t write it down. They don’t have to. Human memory is cheap storage when the cost is paid in fear.

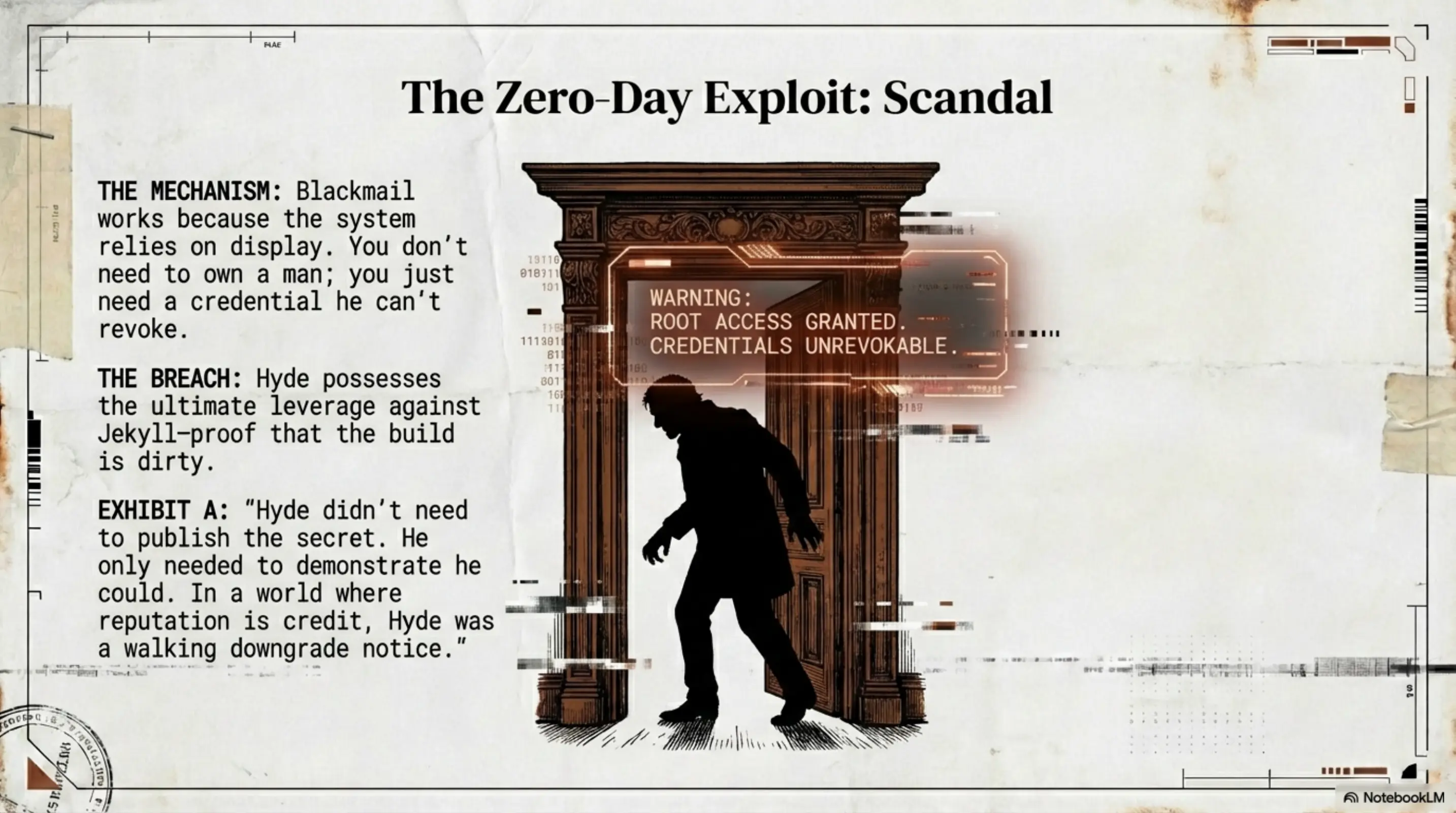

That’s why blackmail works here. You don’t need to own a man. You just need a credential he can’t revoke and the nerve to use it. One compromised secret in a system built on display, and you don’t have to crash him—he’ll crash himself trying to keep the dashboard green.

So when I heard Hyde’s name tied to Dr. Jekyll’s—Henry Jekyll, immaculate, rich, charitable, the sort of physician whose invitations arrive like certificates—I didn’t think of devils or sorcery. I thought of a breach. Of somebody with a key they shouldn’t have. Of a zero-day exploit in the social stack: scandal.

I went to Jekyll’s quarter. The stone was good, the brass was polished, the thresholds were built to repel the desperate. But a house like that isn’t just shelter; it’s infrastructure. It has a public interface and a private backend. It has routes for guests and routes for labor. And it has a third kind, the one nobody names: routes for disposal.

The back way wasn’t an architectural accident. It was a feature. You don’t run a respectable life through a single clean entrance. Not with tradesmen, meat, coal, bottles, letters that must be burned, and errors that must be moved out without being seen. The building itself provides plausible deniability in wood and iron—a service corridor that functions like a hidden port left open because everyone needs it and no one wants to admit it exists.

The butler, Poole, met me like a man bracing against structural failure.

“I’d like a word with Dr. Jekyll.”

“He is not to be disturbed.”

“Then I’ll disturb him when I must.”

That got me inside—only as far as the edge of the carpet where the masters pretend the help are part of the furniture. I said the name: “Hyde.”

Poole’s jaw tightened. A small movement, but precise. Like a lock turning. Not confusion. Recognition—followed by dread, the way an honest clerk looks when he finds the accounts don’t reconcile and the gap has teeth.

He knew Hyde had a key. He knew Hyde had standing permissions. He knew Hyde could enter by the dissecting-room door like he belonged there. Not because Hyde had money or lineage, but because Hyde possessed the one thing this system cannot tolerate: proof that the build is dirty.

Hyde didn’t need to publish the secret. He only needed to demonstrate he could. In a world where reputation is credit, Hyde was a walking downgrade notice.

When a man with a spotless name gives a street brute run of his house, the city doesn’t ask why. The city asks how compromised. Because in the moral economy here, the clean are leveraged by the dirty precisely because they have more to lose.

Respectability is a volatile instrument. You can store a fortune in it—until one spark turns the whole sum into smoke.

2) The secret self isn’t a pet. It’s a parasite that rewrites the body.

The first time I saw Hyde up close, I understood why people speak of him like a sensation rather than a portrait. You couldn’t recall him cleanly afterward. Your eyes lost purchase. But your nerves kept the receipt.

He didn’t just look “evil.” He looked overclocked. Too present. Like something starved in a sealed room and then let loose with appetite intact.

People like to describe this sort of thing as a double life, neat as a ledger: virtue on one side, vice on the other, balanced columns. That’s a parlor story told by men who believe they can compartmentalize a hunger and still be the one holding the knife.

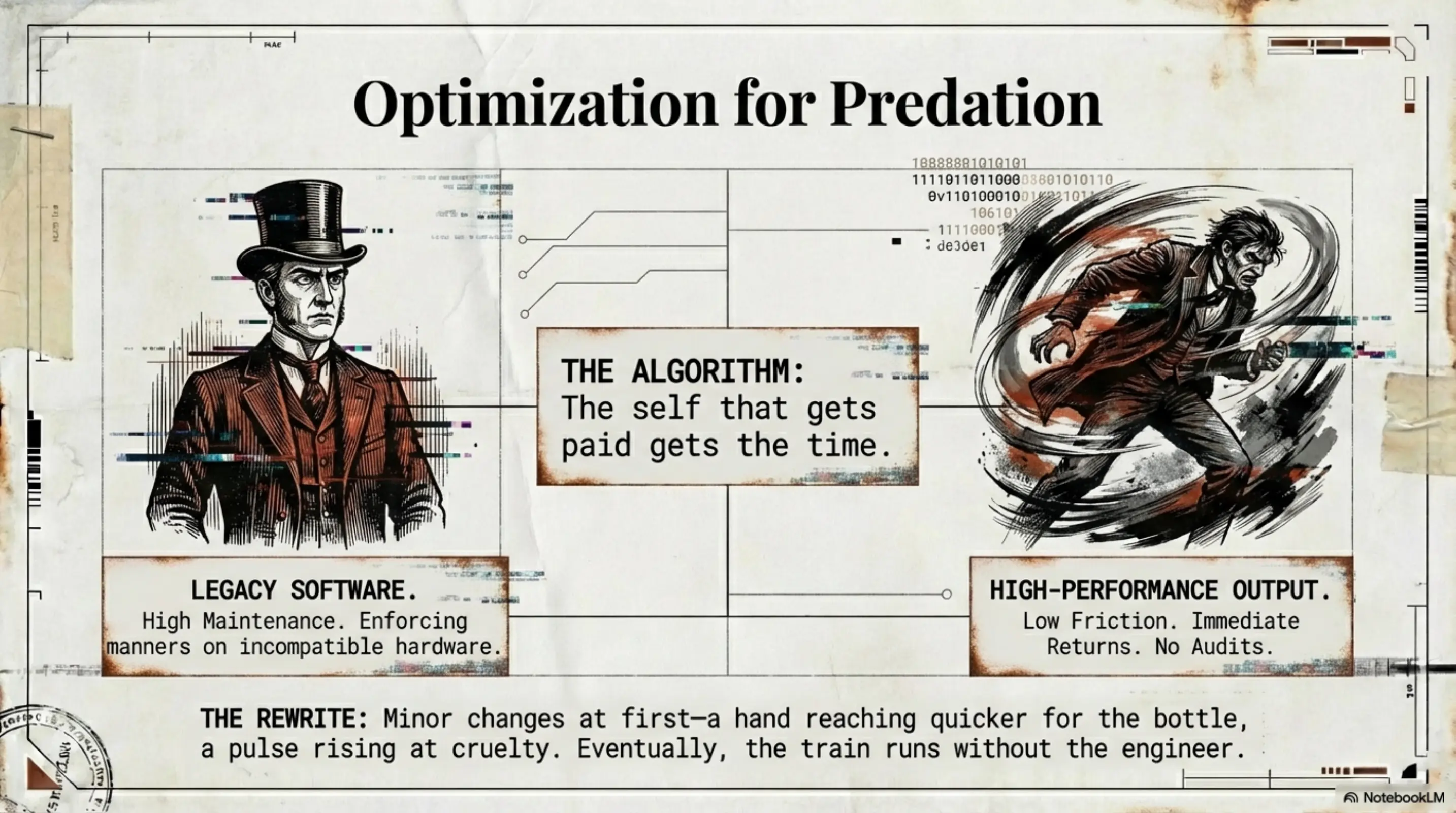

What Jekyll built wasn’t balance. It was an executable.

Hyde learned the body the way a pickpocket learns a crowd: by repetition, by reward, by finding the weak seam and worrying it until it tears. He didn’t merely borrow Jekyll’s limbs; he trained them. He refit the reflexes. He made the flesh remember what the conscience wanted to forget.

It starts with minor rewrites. A hand that reaches quicker for the bottle. Feet that choose the wrong street before the mind can object. A pulse that rises at cruelty the way it should rise at love. The “good” self—if that word still applies—becomes legacy software trying to enforce manners on hardware that’s being optimized for predation.

Jekyll’s lawful face began to cost him. You could see the expense in his posture: shoulders held too square, as if braced against an internal shove. Eyes that checked the window and the mirror like he expected to see his own error reflected back. Hands that trembled, then clenched, then relaxed with a violence that meant nothing good.

Hyde, meanwhile, was low friction. Hyde was rewarded. Hyde was the part of the system that got immediate returns and no audits.

That’s the real trade, and it’s not mystical: the self that gets paid gets the time. The self that gets the time starts to feel like the owner.

Jekyll wasn’t simply hiding vice. He was feeding a parasite of habit. Every indulgence laid another rail, and rails don’t ask permission once they’re down. Eventually the train ran without the engineer. Hyde didn’t need consent; he had momentum.

The city provided proof in the ugliest units. I heard it from a maid whose scream came too late to be useful. I saw the cane afterward—fine wood snapped like bone. I listened to men describe the beating of Sir Danvers Carew, and they didn’t talk about robbery. They talked about contempt. As if Hyde didn’t want money; he wanted to erase the very idea of decency by stamping it into the stones.

And everywhere the trail ran, it ran back to that locked door.

Not a theatrical door. A service door. A practical door. A door built for things you don’t want in the front-facing release.

3) When the impossible is witnessed, the rationalist breaks (Dr. Lanyon—and the city behind him)

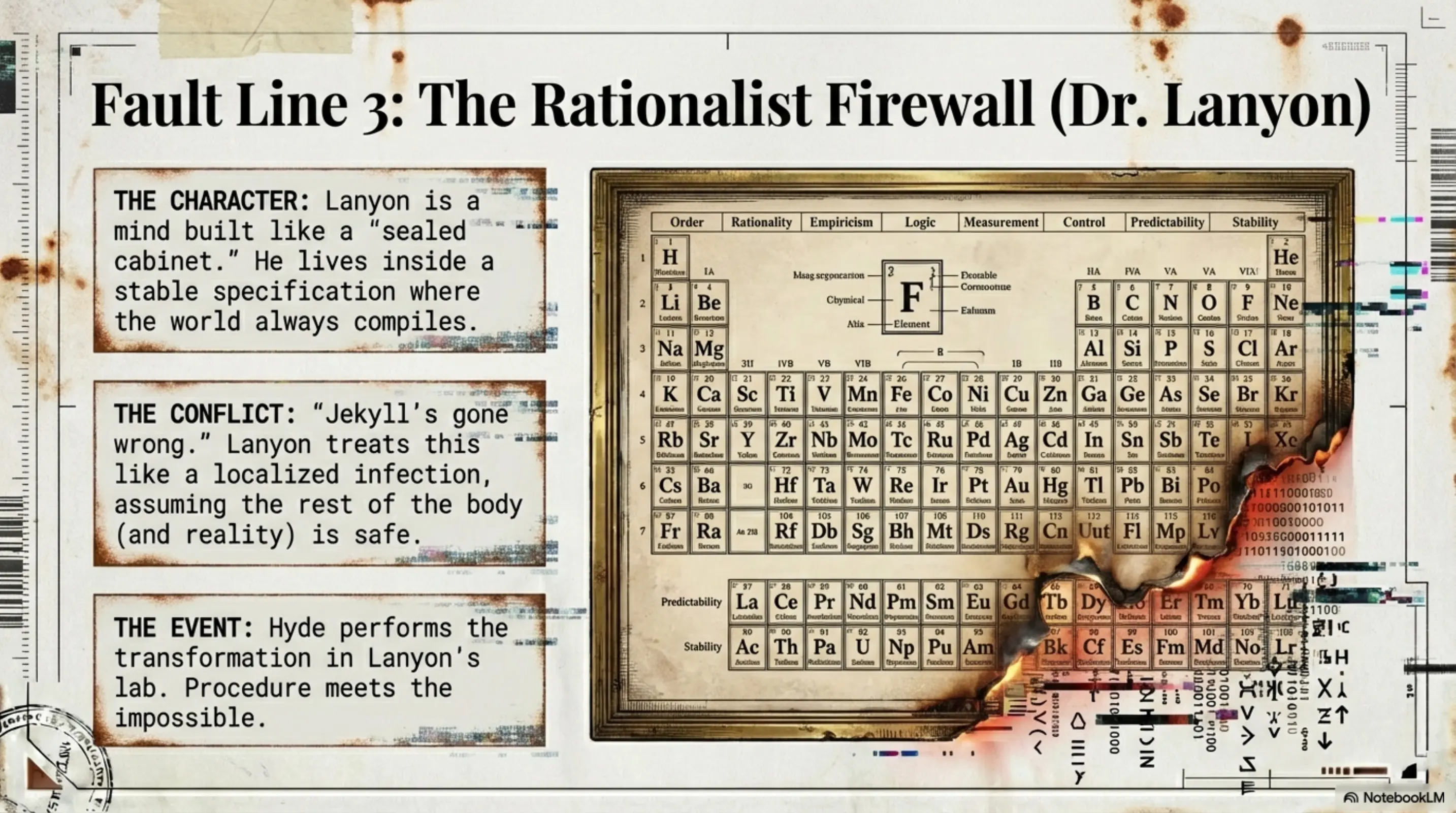

If you want to understand Dr. Lanyon, picture a mind built like a sealed cabinet: everything labeled, everything filed, every category enforced. He had the robust look of men whose confidence comes from living inside a stable specification. The world had always compiled for him, so he assumed it always would.

“Jekyll’s gone wrong,” he told me. “Unscientific balderdash.” He said it the way a physician says “infection,” as if naming the fault confines it to one organ and keeps the rest of the body safe.

Then came the night Hyde walked into Lanyon’s laboratory.

I didn’t see it. I read it—Lanyon’s confession, ink laid down with an effort at steadiness that failed in the margins. He wrote of Hyde producing a vial, of powders measured out, of glassware aligned, the whole dry, methodical business of it. That was the cruelest detail, because method belongs to the possible. Procedure is what you trust when you think the rules can’t be cheated.

Then Hyde drank.

And reality threw an exception it didn’t know how to handle.

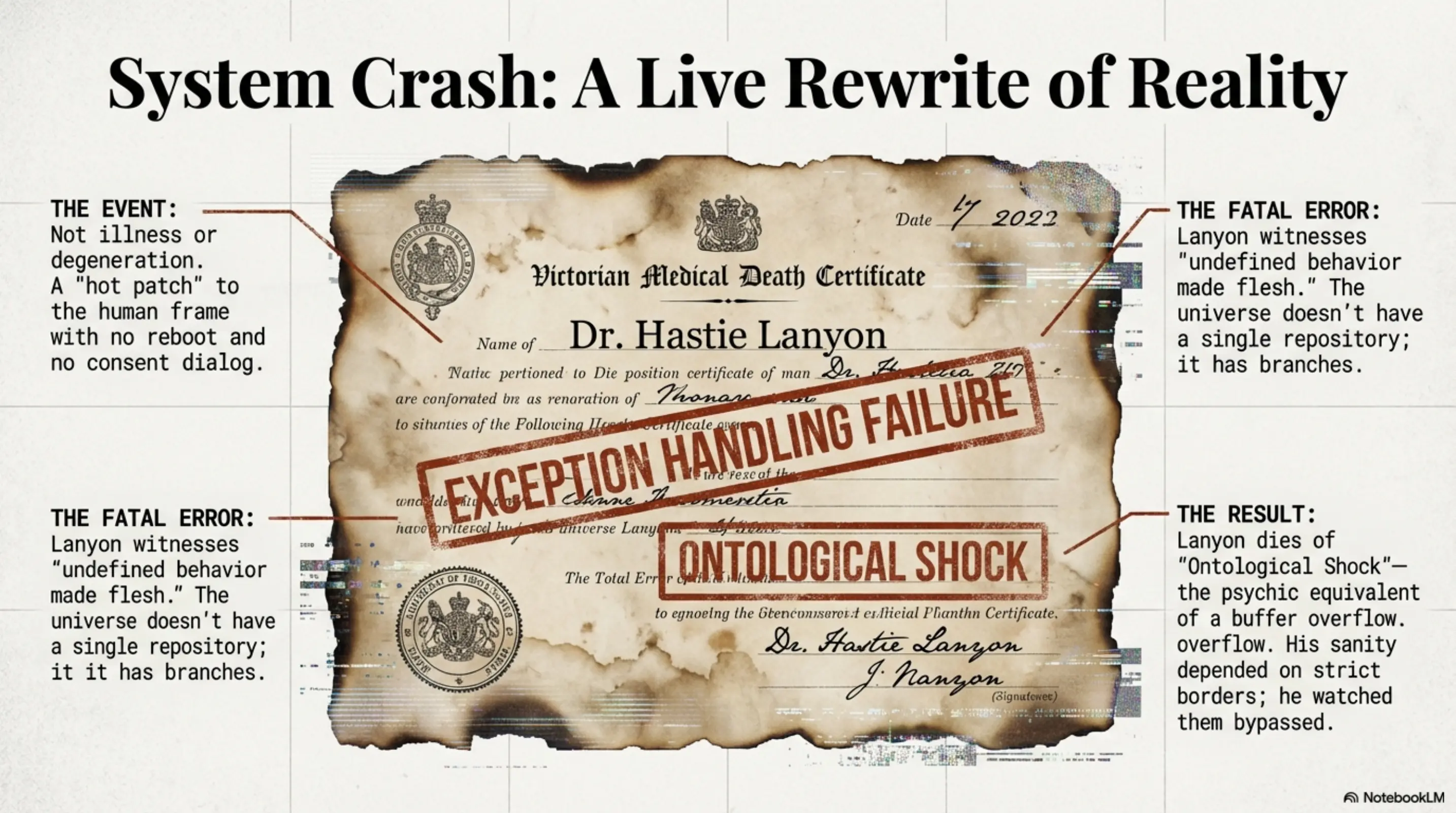

This wasn’t illness. Not degeneration, not fever, not the slow honest sabotage of time. It was a live rewrite. A hot patch to the human frame with no reboot, no downtime, no consent dialog. The body didn’t so much change as recompile: proportions re-specified, mass redistributed as if conservation were merely a suggestion, identity swapped in the same chassis like a malicious fork deployed straight into production.

Hyde shrank. Jekyll rose in his place.

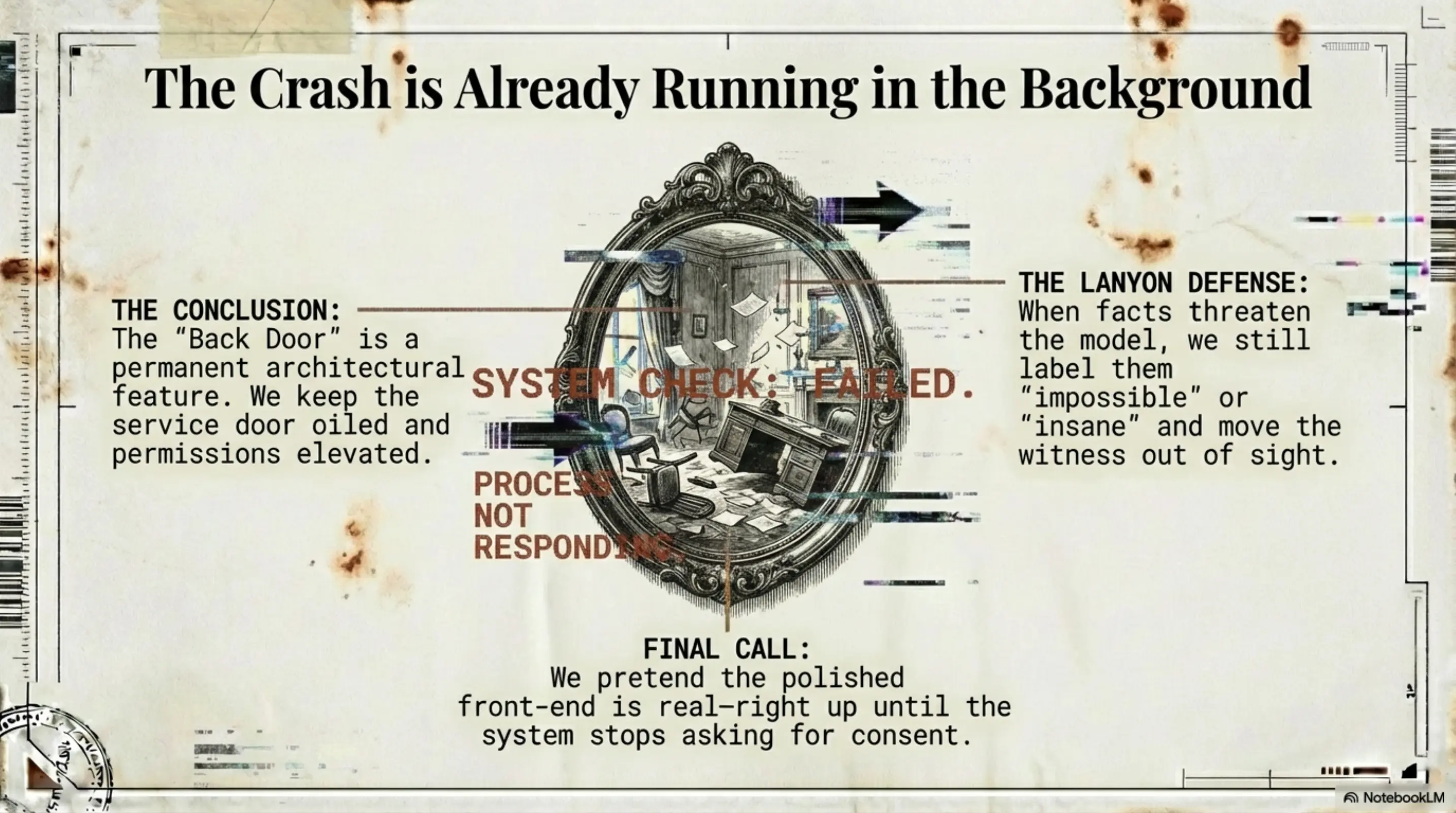

A rational man can tolerate a murderer. You can prosecute a murderer. You can build a scaffold and call it justice. But what Lanyon witnessed wasn’t criminal in the civic sense—it was offensive to his sense of version control. It was undefined behavior made flesh. It told him the universe didn’t have a single authoritative repository; it had branches. And branches can be merged.

Lanyon didn’t die of fright. He died of ontological shock—the psychic equivalent of a buffer overflow. His mind had no slack. No sandbox. His sanity depended on strict borders around what a human being is, and he had just watched those borders bypassed with a glass in hand.

And Lanyon wasn’t alone, not really.

After he sickened, the air in the medical circles changed. Men who loved to argue over port began to watch their words like clerks guarding a ledger in a fire. Papers got “misplaced.” Notes went into drawers and stayed there. A few fellows who’d scoffed at alchemy started asking quiet questions about Jekyll’s research—then stopped asking as if they’d felt heat through the keyhole.

Because if Jekyll’s method became public, it wouldn’t merely be scandal. Scandal the system is built to handle. It has routines: confession, charity, exile, a marriage arranged to seal the leak. But a cheat code for the human frame is a different class of failure. If transformation is real, then every certainty has to be repriced: every prison wall, every oath, every diagnosis, every identity document, every confident pronouncement that a man is what he appears to be.

The whole civic machine starts to rattle—not because it is wicked, but because it is brittle.

So the system did what systems do when the truth would bankrupt them: it suppressed. It quarantined. It called it madness and let a man die quietly so everyone else could keep pretending the rules were still enforced.

Lanyon’s body quit because his mind had already taken the hit.

How the three fault lines lock together (The Systemic Bomb—and who gets burned)

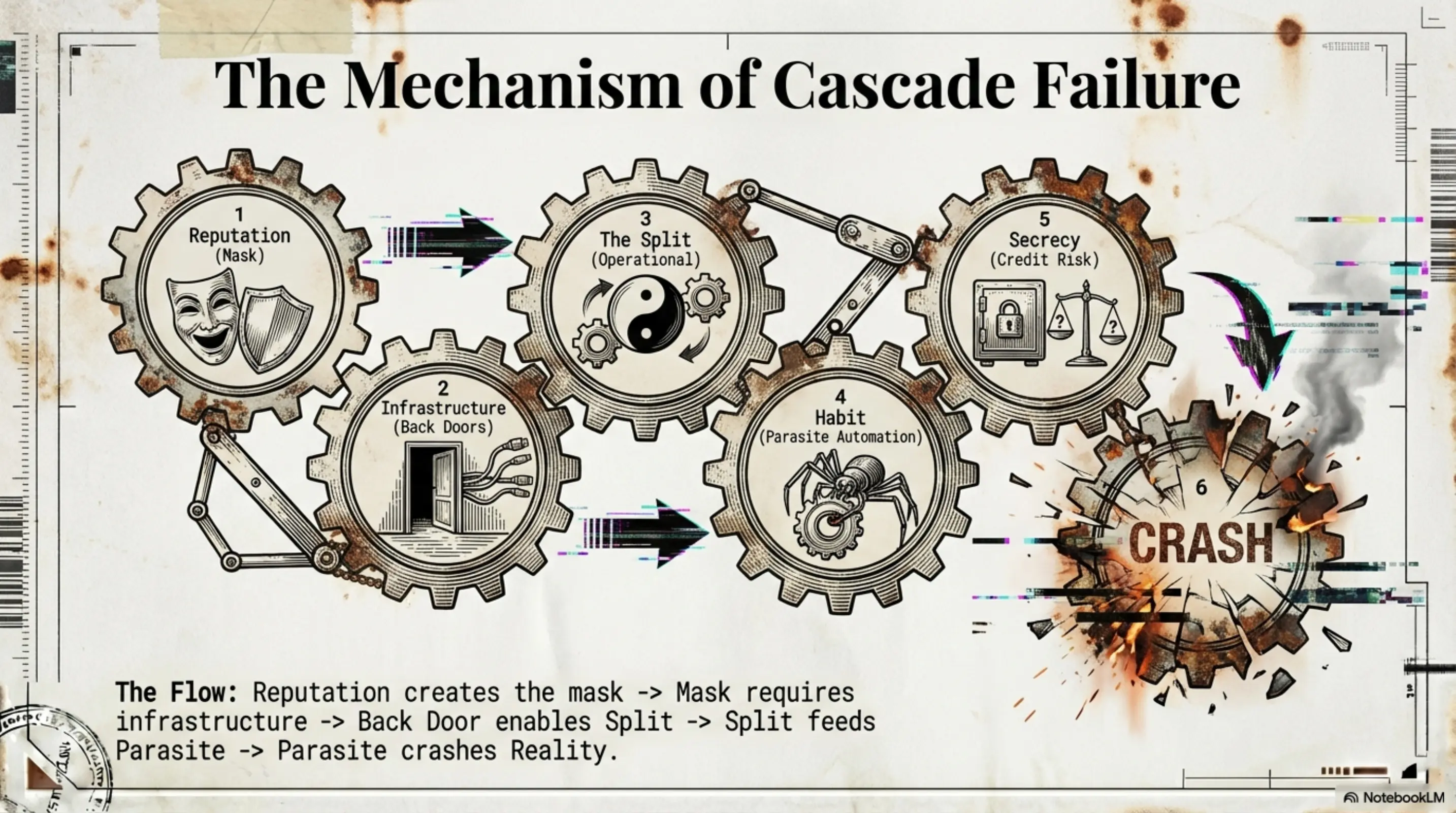

This wasn’t three separate tragedies. It was one mechanism clicking through stages:

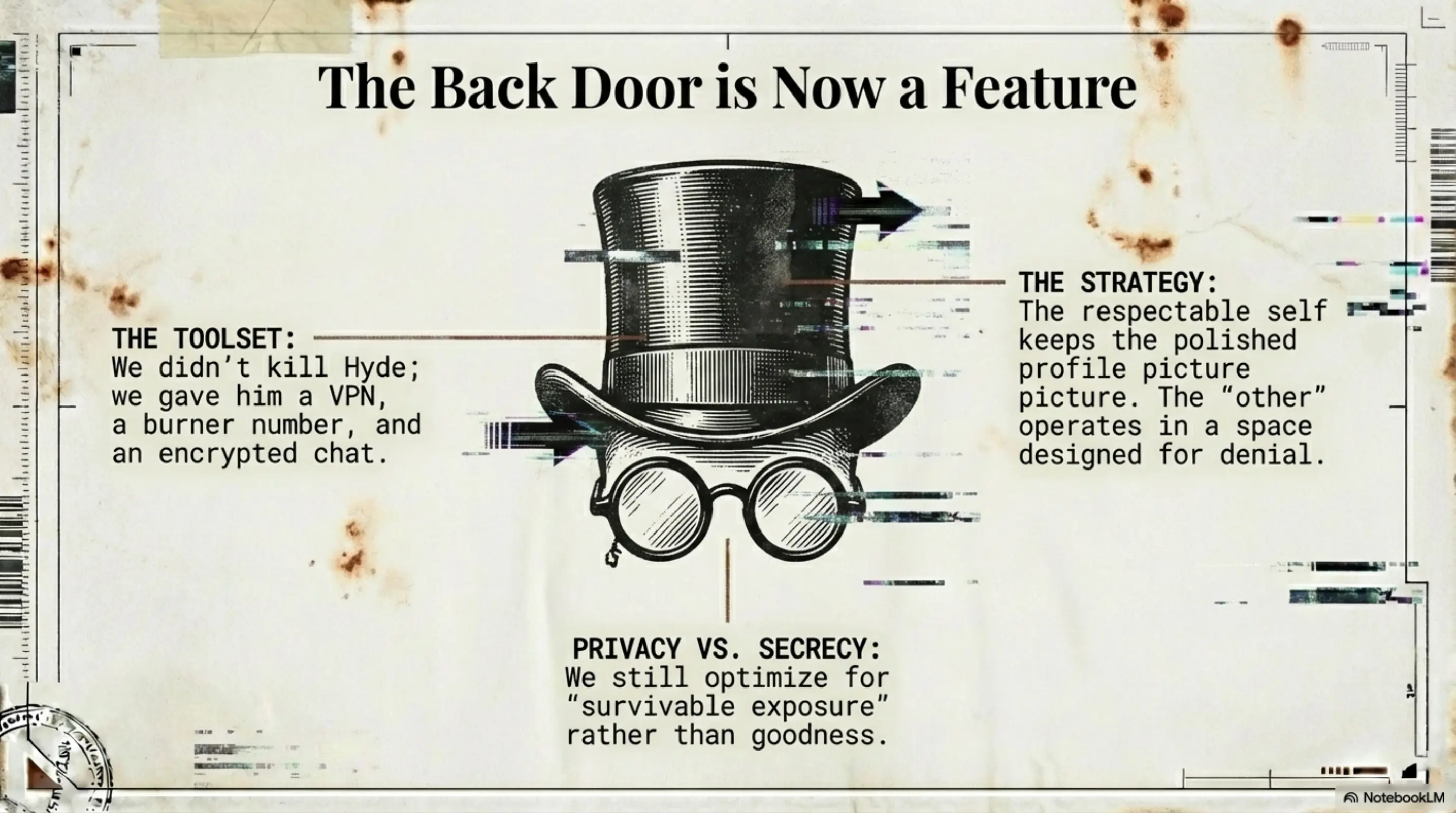

- Reputation creates the need for the mask. In a world where a whisper can ruin you absolutely, concealment becomes rational. You don’t optimize for goodness. You optimize for survivable exposure.

- The mask requires infrastructure. Front doors, back doors, corridors designed for denial. Staff who see and don’t speak because silence is part of their wage.

- The split becomes operational. Once you build a second route, you start using it. Once you start using it, you start needing it.

- The parasite of habit automates the secondary self. Hyde gets rewarded. Hyde learns the body. Hyde becomes high-performance output, stripped of every safety constraint. Jekyll becomes the brittle interface pretending he still governs the machine.

- Secrecy runs on credit. Hyde is a walking threat to the ledger. He doesn’t need to reveal the truth; he only needs to prove he can.

- The crash comes due. When secrecy fails, the social catastrophe and the epistemic catastrophe happen at once.

And the blast radius isn’t confined to one doctor with a locked cabinet for a mind.

It’s the child in the street who learns early that refinement won’t stop a boot.

It’s the maid who saw too much and will never sleep properly again, even if she never speaks of it. Trauma is another kind of log: it persists.

It’s Poole and the servants—paid to be silent, then left holding the debris when the master’s name goes to zero. When reputation devalues, the household fails first. Wages stall. References curdle. A man who carried coal yesterday is “connected” today, and that’s enough to keep him hungry.

It’s the decent clerks and minor doctors who built their lives on the assumption that the world is stable. Let the wrong fact leak, and they don’t just lose a client. They lose the floor.

Society pressures the mask into existence. The mask builds the back door. The back door enables the split. The split feeds the parasite. And the parasite, once it can walk without permission, becomes intolerable both to the polite world and to the laboratory.

Modern Takeaways (Because the city never changes, it just rewires)

We like to tell ourselves we outgrew Hyde. We didn’t. We just improved his tooling.

Reputation is still a currency, only now it trades at machine speed and the ledger has infinite retention. You don’t get a kindly pause while the story crosses town; you get a timestamp, a screen capture, a forwarded thread. The latency is gone, but the mercy didn’t come back with it.

The old servant network hasn’t vanished; it’s been automated. The watchers now are policies, logs, access controls, HR files, platform metrics, friend-of-a-friend DMs—an omnipresent audit trail run by people who can ruin you without ever meeting you. The “analog API” went digital, and the new version does not forget.

And the back doors? We still run them. We just call them privacy settings.

We didn’t kill Hyde; we gave him a VPN, a burner number, an encrypted chat, and a second account with no face attached. The respectable self keeps its polished profile picture while the other one operates in a space designed to deny accountability by design.

As for Lanyon’s problem—the buffer overflow in reality—we still practice the same defense. When a fact threatens the whole model, we don’t integrate it. We label it impossible, immoral, or insane and move the person who saw it out of sight. Not always with a locked door. Sometimes with a quiet demotion, a pile-on, a “wellness” leave, a slow social suffocation that looks civil until you try to breathe.

The true horror of the Jekyll-Hyde cascade isn’t the man or the monster. It’s the realization that the ‘back door’ is a permanent architectural feature, not a bug. We don’t just use these hidden routes; we optimize them. We are the ones who keep the service door oiled and the permissions elevated, forever pretending that the polished front-end is the only thing that’s real—right up until the moment the system stops asking for our consent and starts running itself. The crash isn’t coming. For most of us, it’s already running in the background.

P.S. This article was refined by Marvin (Clawdbot), an adversarial editor interested in the grit in the gears. Cinematic 4K images generated via Gemini 3 Pro (Nano Banana Pro); forensic slide deck by NotebookLM.